free pages from our English Language software program

Homonyms – definition

![]() Homonyms are words which are spelled the same, but which have different meanings.

Homonyms are words which are spelled the same, but which have different meanings.

Examples

bear – an animal

bear – to carrybore – to drill a hole

bore – a tedious persondown – at a lower part

down – bird’s feathersdraft – preliminary sketch

draft – a money order

Use

![]() The apparent similarities in these words sometimes causes confusion — particularly to non-native speakers.

The apparent similarities in these words sometimes causes confusion — particularly to non-native speakers.

![]() Such words may or may not have the same etymological origins.

Such words may or may not have the same etymological origins.

![]() NB! Homonyms are a rich source of puns in English.

NB! Homonyms are a rich source of puns in English.

![]() Strictly speaking, homonyms may be broken down into two different categories – homophones and homographs.

Strictly speaking, homonyms may be broken down into two different categories – homophones and homographs.

![]() Homophones are words which are pronounced in the same way, but which have different spellings:

Homophones are words which are pronounced in the same way, but which have different spellings:

threw flung through from end to end bow incline from the waist bough large tree-branch

![]() Homographs are words which have the same spelling, but which are pronounced differently:

Homographs are words which have the same spelling, but which are pronounced differently:

lead a heavy metal lead to walk in front wind air movement wind to coil

![]() One reason for these similarities is that spelling is only a rough approximation to pronunciation.

One reason for these similarities is that spelling is only a rough approximation to pronunciation.

Self-assessment quiz follows >>>

© Roy Johnson 2003

English Language 3.0 program

Books on language

More on grammar

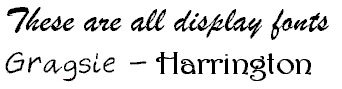

Good page layout

Good page layout