tutorial, characters, film versions, study resources

Lolita (1955) is without doubt Nabokov’s masterpiece – a tour de force of fun and games in both character, plot, and linguistic artistry. And yet its overt subject is something now considered quite dangerous – paedophilia. A sophisticated European college professor goes on a sexual joy ride around the USA with his teenage step-daughter. He evades the law, but drives deeper and deeper into a moral Sargasso, and the end is a tragedy for all concerned. There are wonderful evocations of middle America, terrific sub-plots, and language games with deeply embedded clues on every page. You will probably need to read it more than once to work out what is going on, and each reading will reveal further depths.

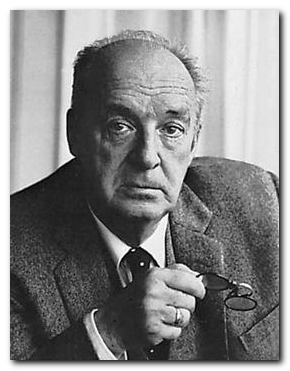

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov is one of the great twentieth-century writers. He wrote of himself: “I was born in Russia and went to university in England, then lived in Germany for twenty years before emigrating to the United States.” The first half of his oeuvre was written in Russian; then he switched briefly to French, and then permanently to English. He also spent a third period of exile living in Geneva, and translating his earlier works from Russian into English.

Nabokov loves word-play, stories that pose riddles, and games which keep readers guessing. Above all, he loves jokes. He produces witty and intellectual writing – and yet persistently draws our attention to moments of tenderness and neglected sadness in life. It is lyric, poetic writing, in the best sense of these terms. Yet be prepared for black humour and unashamed tenderness – often on the same page. And be sure to keep a dictionary on hand.

Lolita – plot summary

Lolita is narrated by Humbert Humbert, a literary scholar born in 1910 in Paris, who is obsessed with what he refers to as ‘nymphets’. Humbert suggests that this obsession results from his failure to consummate an affair with a childhood sweetheart before her premature death. In 1947, Humbert moves to Ramsdale, a small New England town. He rents a room in the house of Charlotte Haze, a widow, mainly for the purpose of being near Charlotte’s 12-year-old daughter, Dolores (also known as Dolly, Lolita, Lola, Lo, and L).

Lolita is narrated by Humbert Humbert, a literary scholar born in 1910 in Paris, who is obsessed with what he refers to as ‘nymphets’. Humbert suggests that this obsession results from his failure to consummate an affair with a childhood sweetheart before her premature death. In 1947, Humbert moves to Ramsdale, a small New England town. He rents a room in the house of Charlotte Haze, a widow, mainly for the purpose of being near Charlotte’s 12-year-old daughter, Dolores (also known as Dolly, Lolita, Lola, Lo, and L).

While Lolita is away at summer camp, Charlotte, who has fallen in love with Humbert, tells him that he must either marry her or move out. Humbert reluctantly agrees in order to continue living near Lolita. Charlotte is oblivious to Humbert’s distaste for her and his lust for Lolita until she reads his diary. Upon learning of Humbert’s true feelings, Charlotte is appalled: she makes plans to flee with Lolita and threatens to expose Humbert’s perversions. But as she runs across the street in a state of shock, she is struck and killed by a passing car.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms.

Lolita and Humbert drive around the country, moving from state to state and motel to motel. Humbert initially keeps the girl under control by threatening her with reform school; later he bribes her for sexual favours, though he knows that she does not reciprocate his love and shares none of his interests. After a year touring North America, the two settle down in another New England town. Humbert is very possessive and strict, forbidding Lolita to take part in after-school activities or to associate with boys; the townspeople, however, see this as the action of a loving and concerned, if old fashioned, parent.

Lolita begs to be allowed to take part in the school play; Humbert reluctantly grants his permission in exchange for more sexual favours. The play is written by Clare Quilty. He is said to have attended a rehearsal and been impressed by Lolita’s acting. Just before opening night, Lolita and Humbert have a ferocious argument, which culminates in Lolita saying she wants to leave town and resume their travels.

As Lolita and Humbert drive westward again, Humbert gets the feeling that their car is being tailed and he becomes increasingly suspicious. Lolita falls ill and must convalesce in a hospital; Humbert stays in a nearby motel. One night, Lolita disappears from the hospital; the staff tell Humbert that Lolita’s ‘uncle’ checked her out. Humbert embarks upon a frantic search to find Lolita and her abductor, but eventually he gives up.

One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.

One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.

Humbert asks Lolita to leave her husband and return to him, but she refuses, breaking Humbert’s spirit. He leaves Lolita forever, kills Quilty at his mansion in an act of revenge and is arrested for driving on the wrong side of the road and swerving. The narrative closes with Humbert’s final words to Lolita in which he wishes her well.

The narrative has been written by Humbert in jail, whilst he is awaiting his trial for murder. But a ‘forward’ to the novel supposedly written by a psychiatrist, tells us that Humbert died of coronary thrombosis upon finishing his manuscript. Lolita too died whilst giving birth to a stillborn girl on Christmas Day, 1952.

Lolita – video documentary

Lolita – study resources

![]() Lolita – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Lolita – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Lolita – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Lolita – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon UK

The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon UK

![]() The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon US

The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon US

![]() Lolita: A Reader’s Guide – Amazon UK

Lolita: A Reader’s Guide – Amazon UK

![]() Lolita: A Reader’s Guide – Amazon US

Lolita: A Reader’s Guide – Amazon US

![]() Lolita: A Casebook – Amazon UK

Lolita: A Casebook – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

![]() Lolita – the 1965 Stanley Kubrick film version – Amazon UK

Lolita – the 1965 Stanley Kubrick film version – Amazon UK

![]() Lolita – the 1998 Adrian Lyne film version – Amazon UK

Lolita – the 1998 Adrian Lyne film version – Amazon UK

![]() Lolita – audiobook version – Amazon UK

Lolita – audiobook version – Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Biography: Vol 1 – Amaz UK

Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Biography: Vol 1 – Amaz UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years – Biography: Vol 2 – Amaz UK

Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years – Biography: Vol 2 – Amaz UK

![]() Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

![]() The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

![]() First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection

First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection

![]() Lolita USA – Humbert’s and Lolita’s journeys across America

Lolita USA – Humbert’s and Lolita’s journeys across America

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Lolita – principal characters

| Humbert Humbert | literary ‘scholar’ aged 37, heir to perfume company |

| Charlotte Haze | bourgeois American housewife and widow |

| Dolores (Lolita) Haze | Charlotte’s precocious 12 year old daughter |

| Clare Quilty | playwright, playboy, and pornographer |

| Annabel Leigh | Humbert’s 12 year old childhood love |

| Valeria | Humbert’s first wife, who leaves him for a Russian taxi driver |

| Dick Schiller | a working man who Lolita marries after she escapes from Quilty |

| Rita | an alcoholic who Humbert lives with after Lolita leaves him |

| Mrs Pratt | the short-sighted headmistress at Lolita’s school |

| Mona | Lolita’s school friend who flirts with Humbert |

| Gaston Grodin | a plump gay French professor at Lolita’s school |

| Vivian Darkbloom | Quilty’s female writing partner |

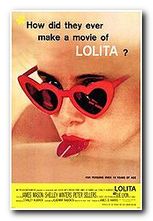

Lolita – film versions

![]() See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

Lolita – the main theme

In an afterward to his novel — ‘On a Book Entitled Lolita‘ — written a year after it was first published, Nabokov sought to explain the genesis of the story which had caused such a scandal when it appeared in 1955.

the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage. The impulse I record had no textual connection with the ensuing train of thought which resulted, however, in a prototype of my present novel, a short story some thirty pages long … but I was not pleased with the thing and destroyed it some time after moving to America in 1940.

This is a rather typically Nabokovian piece of post-rationalisation. He was much given to controlling and re-shaping his life to suit his own purposes. Fortunately, the novella-length work he mentions was not destroyed, but was recovered later and published in 1987 as The Enchanter. This tells the story of a middle-aged man who has a passion for little girls, and one day becomes besotted by a twelve year old. He marries her mother to gain access to her, and after the mother dies takes the girl away to a hotel. She wakes up to find him introducing her to his ‘magic wand’, and when she screams in terror he runs out into the street and is killed by a passing truck.

But the theme of a middle-aged man’s passion for young girls goes back further than that. Laughter in the Dark (1932) features a middle-aged art critic who becomes obsessed with a sixteen year old girl who he seduces and runs away with, abandoning his wife. And in the short story A Nursery Tale written as early as 1926, the principal character Erwin is in search of girls to help him fulfil a sexual fantasy. He chooses ‘a child [my emphasis] of fourteen or so in a low-cut party dress … mincing at [an] old poet’s side … her lips were touched up with rouge. She walked swinging her hips very, very slightly’.

And lest it be thought that these are unusual examples, it has to be said that the same theme occurs in later works such as Transparent Things (1972) Ada (1969) which combines the theme with incest between the two principal characters, and his last uncompleted novel The Original of Laura first published in 2009. This features the sexual life of a flirty young girl called Flora aged twelve who is pursued lecherously by an ageing roué called (believe it or not) Hubert H. Hubert.

What does all this add up to? Well, certainly the claim that the Lolita theme is not something that suddenly came to Nabokov out of a newspaper via a painting ape. He was writing about what we currently call paedophilia throughout his life. Fortunately he wrote about many other things as well, but his admirers have to take on board this feature which Martin Amis calls ‘an embarrassment’.

Lolita – further reading

![]() David Andrews, ‘Aestheticism, Nabokov, and Lolita‘. Vol. 31, Studies in American Literature. Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, 1999.

David Andrews, ‘Aestheticism, Nabokov, and Lolita‘. Vol. 31, Studies in American Literature. Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, 1999.

![]() Alfred Appel Jr, The Annotated Lolita. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Alfred Appel Jr, The Annotated Lolita. New York: Vintage, 1991.

![]() Harold Bloom, ed. Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Harold Bloom, ed. Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

![]() Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

![]() Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

![]() Harvey Breit, ‘In and Out of Books’. Review of Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov. New York Times Book Review, Feb. 26, 1956, p. 8, and March 11, 1956, p. 8.

Harvey Breit, ‘In and Out of Books’. Review of Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov. New York Times Book Review, Feb. 26, 1956, p. 8, and March 11, 1956, p. 8.

![]() Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

![]() Christine Clegg, Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Lolita’: A Reader’s Guide to Essential Criticism, London: Macmillan, 2000

Christine Clegg, Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Lolita’: A Reader’s Guide to Essential Criticism, London: Macmillan, 2000

![]() Julian W. Connoly (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Julian W. Connoly (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

![]() Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

![]() Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

![]() Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

![]() Ellen Pifer, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: A Casebook, Oxford University Press, 2002.

Ellen Pifer, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: A Casebook, Oxford University Press, 2002.

![]() David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

![]() Marianne Sinclair, Hollywood Lolitas: The Nymphet Syndrome in the Movies. New York: Henry Holt, 1988.

Marianne Sinclair, Hollywood Lolitas: The Nymphet Syndrome in the Movies. New York: Henry Holt, 1988.

![]() Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Film version

Adrian Lyne’s 1997 version

starring Jeremy Irons, Melanie Griffith, Dominique Swain

![]() See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

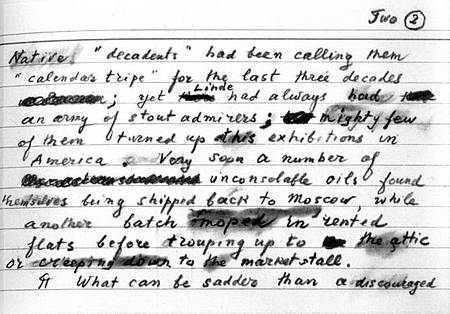

Nabokov’s writing methods

Nabokov created all of his novels using ordinary 6″ X 4″ office index cards, on which he wrote in pencil. He claimed that he would first of all compose the novel completely in his head, before doing any writing. Then he would write sections of it on the cards, which he could then arrange in any order. This gave him the freedom to work on any section of the novel that he pleased.

The publication of his posthumous fragment of a novel, The Original of Laura, proves that this was not entirely true. The book combines photocopies of its index cards with a transcription of their contents, and they make it quite clear that he was at many points making up the story as he went along.

Despite his claims to be meticulously correct about very single detail of everything he wrote, his cards for The Original of Laura demonstrate that he made spelling mistakes, grammatical errors, and he revised heavily most of what he wrote. This of course is similar to the way in which most other writers compose their works.

from The Original of Laura

Nabokov discusses Lolita

In conversation with Lionel Trilling – late 1950s

Part two of the same conversation

Other work by Vladimir Nabokov

Pale Fire is a very clever artistic joke. It’s a book in two parts – the first a long poem (quite readable) written by an American poet who we are encouraged to think of as someone like Robert Frost. The second half is a series of footnoted commentaries on the text written by his neighbour, friend, and editor. But as we read on the explanation begins to take over the poem itself, we begin to doubt the reliability – and ultimately the sanity – of the editor, and we end up suspended in a nether-world, half way between life and illusion. It’s a brilliantly funny parody of the scholarly ‘method’ – written around the same time that Nabokov was himself writing an extensive commentary to his translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

Pale Fire is a very clever artistic joke. It’s a book in two parts – the first a long poem (quite readable) written by an American poet who we are encouraged to think of as someone like Robert Frost. The second half is a series of footnoted commentaries on the text written by his neighbour, friend, and editor. But as we read on the explanation begins to take over the poem itself, we begin to doubt the reliability – and ultimately the sanity – of the editor, and we end up suspended in a nether-world, half way between life and illusion. It’s a brilliantly funny parody of the scholarly ‘method’ – written around the same time that Nabokov was himself writing an extensive commentary to his translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories