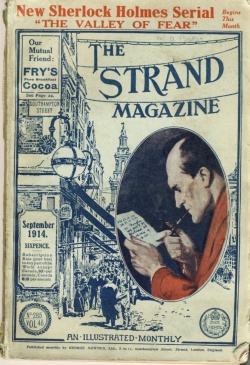

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a total of fifty-nine Sherlock Holmes stories – most of which appeared in The Strand Magazine between 1887 and 1927. The stories made Doyle rich and brought thousands of readers to the magazine. Sherlock Holmes became so popular as a character that Doyle thought the stories were interfering with what he regarded as his more serious literary ambitions. In 1893 he killed off his hero in a famous story The Final Problem where Holmes is pulled to his death by arch rival Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland.

This created such an outcry and a public demand for more stories (particularly in the United States) that Doyle was forced to ‘resurrect’ Holmes. He did this rather cleverly by creating new stories that dealt with cases from a time before his demise.

Origins

It is quite clear that the character of Sherlock Holmes is based largely on Edgar Allan Poe’s famous detective Auguste Dupin. Holmes leads a largely solitary and slightly bohemian life; he operates as a private detective; and he solves his cases not by action but by a process which combines acute observation of details with a rigorous system of logical induction. All of these characteristics are identical to those of Auguste Dupin.

Structure

A typical story is related by his friend Doctor Watson as a first person narrator. A retired medical orderly from the war in Afghanistan, Watson takes up bachelor residence with Holmes at the famous apartments 221B Baker Street. Later in the series, he marries and lives separately. Sometimes Watson merely acts as an ‘outer narrator’. He introduces the story, then relates Holmes’ account of the mystery and its solution. In just one or two stories Sherlock Holmes himself is the first person narrator (The Lion’s Man and The Blanched Soldier).

Watson often presents a brief character sketch of Holmes – his moodiness, his habits of playing the violin or taking cocaine, and his obsessive recording of previous cases. Then there might follow an example of his inductive method. Holmes for instance more than once presents a perceptive interpretation of Watson’s recent behaviour from a close examination of his shoes.

Then comes the announcement of the mystery to be solved – often accompanied by the arrival of the person who has commissioned the case. The client suddenly appears at 221B Baker Street with a problem which is either a personal and sensitive issue, or one which cannot be solved by the police.

Sherlock Holmes is in fact an amateur consultant detective. He solves problems which might be crimes that have baffled the police, but he also acts in cases which are puzzling to individuals – and sometimes in which no crime has been committed.

His first step in almost all cases is to assemble the details of the case. The reader is thereby presented with the ‘background’ to the problem. This includes baffling circumstances, the skullduggery, or the crime itself – all outlined within the confines of Holmes’ Baker Street consulting rooms.

Holmes then constructs a solution to the problem – but does not say what it is. Proof of his theory is usually required, and this usually involves a trip to either Paddington, Euston, or Victoria railway station. On the journey to their destination he unravels some of the further details to Watson, who is amazed at Holmes’ insights.

Arriving at their destination, (the crime scene or the locus of the problem) Holmes often arranges a fiendish plot or dons some convincing disguise which causes the culprit to reveal him or herself.

It has to be said that in this latter phase of the story, there is often a great deal more background detail provided to explain the origins of the problem or to solve the crime. This is often detail the reader can have no way of knowing from what has been previously dramatised in the story.

It is in this sense that despite their enduring popularity, the Sherlock Holmes stories are pitched at what might be called the tabloid level of literary distinction. They are lightweight, often dryly amusing, and quite entertaining tales. They have even attracted a considerable amount of critical attention – though this is often taken up with naive issues of correspondence between the fictional events of the stories and the ‘real’ London and South-East in which they are situated. (For example – Where exactly is 221B Baker Street?)

But Conan Doyle does not really play fair with his readers. Sherlock Holmes might be a memorable fictional creation; he might have impressive powers of induction; and he might get caught up in thrilling escapades in his work as a consultant detective. But if the solution to the problems he faces comes from a character who suddenly appears in the last pages of a story, the revelation of a hidden trapdoor, or the unannounced arrival of an illegitimate child – then the patient reader has every reason to feel somewhat cheated rather than rewarded.

The best current editions of the Sherlock Holmes stories are those published in the Oxford World’s Classics paperback series. Each volume contains a critical introduction, a note on the text, a bibliography of further reading, a chronology of Arthur Conan Doyle, and most importantly a series of explanatory notes giving historical, geographical, and scientific information about details mentioned in the text.

© Roy Johnson 2018

The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes – Amazon UK

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Amazon US

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes – Amazon UK

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes – Amazon US

The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes – Amazon UK

The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes – Amazon US

More 19C Authors

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories