his life, loves, and works

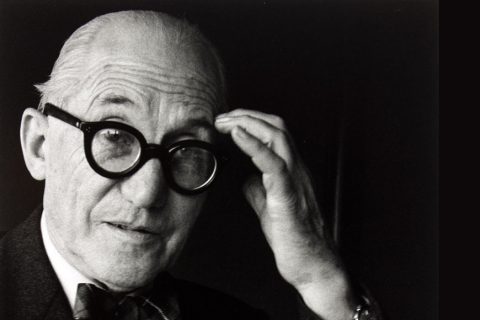

Le Corbusier was born Charles-Edward Jeanneret in 1887 in the Swiss Alps into a modest middle-class family with a culture of hard work, music, and exploration of the countryside at weekends. Although he was not as academically talented as his older brother Albert, he rapidly developed skills in drawing and painting.

He enrolled at the Ecole d’Art and then, without any formal training, began to practise architecture, designing his first house at the age of seventeen. Influenced by his reading of Ruskin, he travelled to Italy, where he was inspired by the cathedrals of Milan, Pisa, and Florence. His trip ended in Vienna, where he hoped to find work. All of these destinations at the time were within the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Vienna was a disappointment: ‘if it weren’t for the music, one would commit suicide’. Despite protests from his family and teacher, he then moved to Paris in 1908. There he encountered something that was to change his life – reinforced concrete. He worked in an architect’s office in the afternoon and continued his own self-generated curriculum of study in the museums and art galleries each morning.

Despite this early success he suddenly decided to go to Germany. There he had the good fortune to be commissioned to write a study on contemporary design developments. This resulted in travel to Frankfurt, Dusseldorf, and Weimar, and the publication of two reports. He also managed to talk his way into an internship with the Peter Behrens practice.

This was followed by a period of acute Weltschmerz from which he emerged with a desire for further travel. He sailed from Vienna down the Danube with a friend to Constantinople, then journeyed on to the monasteries of Mount Athos, which had an inspirational effect on him. As did the Parthenon, which he visited every day for almost a fortnight. He was recalled from this orgy of Mediterraneanism by the offer of a job back home.

Feeling depressed at returning to what he regarded as a provincial backwater, he nevertheless threw himself into teaching theoretical and practical design at the Ecole d’Art. This was something like a precursor to the Bauhaus. He also opened an official office as a practising architect, even though he was completely without professional qualifications.

His first major project was the design and construction of a palatial villa for his parents. The house was a triumph of modernist design, even though he almost ruined the family financially by a budget overspend. A few years later the house had to be sold off at a huge loss, which wiped out his parents’ savings.

During the First World War he designed a cheap and modular system of building to re-house homeless people. He travelled to France and met the artist Maillol, who at that time was considered the world’s leading sculptor. He continued to work on small design projects, but as the war ended he decided to make a new beginning for his life. He moved to live in Paris.

He set himself up in a studio apartment in the rue Jacob, visited prostitutes, and was at the notorious first night performance of Parade in 1917. He also entered his first major architectural competition, which was to design a large scale industrial slaughterhouse for Nevers in central France.

At a social level he befriended his neighbour, the artist Amedee Ozenfant. He also rather bizarrley established a business for the manufacture of reinforced concrete bricks. He and Ozenfant collaborated on the publication of their artistic manifesto – After Cubism – and they exhibited paintings together. At this time he regarded his commercial enterprises and design work as merely sources of income to support his ambition to be a painter.

In 1920 he changed his name from Charles-Edouard Jenneret to Le Corbusier, and together with Ozenfant launched the avant gard magazine L’Esprit Nouveau. He designed another form of modular shoebox-shaped housing called Citrohan, using concrete, steel, and glass. His objective was to make buildings of Spartan simplicity that were filled with light.

He met and began to live with Yvonne Gallis, an earthy Mediterranean-style woman whom he kept more or less secret from his family. (There are unconfirmed rumours that they met in a brothel.). He built a modernist palace for the banker and art collector Raoul La Roche and in 1923 published a major series of theoretical essays as Towards a New Architecture.

A partnership with his younger cousin Pierre Jenneret flourished and they were forced to employ more and more assistants. Le Corbusier still spent his mornings painting, but from this point onwards kept this side of his life almost secret, so that it didn’t dilute his growing reputation as an architect. He complained about being exhausted by the demands of his profession, but in fact his office hours were in the afternoons between 2.00 and 5.00 pm.

His ideas were mocked by critics and the general public because his designs put functionality before all else. The house of the future was given features we now take for granted: built-in wardrobes and storage, open plan rooms, plain walls, large industrial-sized windows, and furniture which he chose from the manufacturers of hospital equipment. Yet despite the criticisms he was becoming a celebrity architect, with requests from Princess de Polignac and the writer Colette. He also designed a very successful villa for Michael Stein, the brother of the American writer Gertrude Stein.

Corbusier engaged with design at all levels of scope and size. For interiors he designed arm chairs and occasional tables; for social housing he created multi-storey residential blocks; and at city level he wanted to re-shape urban areas – to admit light and space where once there had been narrow, crowded streets. For these ambitions, and because he theorised about them, he was widely (but incorrectly) regarded as a communist.

Nevertheless he did visit Moscow in 1926, where he won a commission to design new offices for the Centrosoyuz. He felt his visit was a big success, though some of his ideas were criticised (quite intelligently) by El Lissitsky. He was also invited to South America, where he lectured on urban planning and designed a house for Victoria Ocampo – a friend of the writer Jorge Luis Borges.

He prepared his lectures in advance, then delivered them without notes, illustrating his arguments with fluidly produced diagrams and sketches whilst speaking. On the lecture tour he met the singer Josephine Baker, for whom he was to design a house in Paris. He also took the opportunity to have an affair with her during their ten day transatlantic journey back to France.

In 1930 he made two decisive steps in his public life: he took out French citizenship, and he married Yvonne. Two years later he submitted his plans for the Palace of the Soviets in Moscow, confident that his ideas would be accepted by a regime that had earlier produced the forward-thinking designs of the Constructivists. What he didn’t realise was that Joseph Stalin (like other dictators) had already decreed that all architecture for the proletariat must be Greco-Roman in style. He had more success a year later with the Cite de Refuge – a purpose-built hostel for children and the homeless he built for the Salvation Army in Paris.

When he visited America for a further lecture tour he felt that the skyscrapers were too small and too close together, but he did find a new client – the socialite divorcee Tjader Harris, who also became his lover. However, he was disappointed that no grand schemes in urban projects resulted from his contact with the New World.

When war broke out in Europe he was recruited as advisor to the war ministry (with the rank of colonel). He worked on designing a modular munitions factory, but when the Germans invaded and occupied Paris he fled to Petain’s headquarters in Vichy. It was at this point that his ideas concerning ‘modernity’. ‘The machine age’, and urban planning meshed all too easily with fascist ideology, and he collaborated with people who eventually deported eighty thousand Jews from France to the death camps.

His participation with the regime was in no way passive or accidental. He actively sought the support of Petain himself, and was eventually rewarded with a post on the committee for ‘Habitation and Urbanism’ of Paris. Here he worked alongside racists, eugenicists,and people who advocated euthanasia for ‘cleansing’ the capital’s population. Plagued by bureaucratic indecision and in-fighting, the committee never achieved anything, and Corbusier ended back in Paris running a sort of private college of architecture.

When France was liberated by the Allies in 1944 (and ten thousand collaborators had been executed) Corbusier merely made himself available to the De Gaul government and ever after whitewashed his collaborationist record of the war years. He was given a dream project – to construct a huge modernist apartment block in Marseille..

He was working on several projects simultaneously when invited to join the scheme for a new United Nations headquarters in New York. He jumped at the chance, assuming that he would be its lead architect, even though he did suggest that Alvar Aalto, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe should join the team. The American venture boosted his already supercharged reputation – and ego. It enabled him to re-establish contact with his lover Tjader Harris; and it left his wife back home sinking deeper and deeper into alcoholism.

From time to time he flew back to check on the Marseille project which was coming under criticism from local bureaucrats for what they considered its outlandish design. They objected to kitchens in the same space as dining areas – something considered revolutionary at the time. As soon as he was absent in France, other people took over his design for the UN building, which was eventually attributed to the American architect Wallace K. Harrison.

But Corbusier had compensations – notably a commission to design a new mini-city in the Colombian capital, Bogota, and a new lover in the shape of journalist Hedwig Lauber. There was also an offer to design a new government headquarters in Chandigarh, India, a project personally endorsed by its leader, Pandit Nehru. This was his dream of total urbanisation come true. He was in his element, travelling first class between three continents.

Whilst he was building a city for a government, he constructed for himself a holiday home in the south of France. It was a simple and box-shaped structure that on the outside looked like a log cabin. But the interior was lined with coloured plywood, which created a modernist statement. The single room construction was even made contiguous with the local restaurant whose owner he had befriended. This provided Yvonne with company during his many absences.

His national masterpiece, L’Unite d’Habitation was finished and opened in 1952. It housed three hundred families, had built-in shops and recreational areas, and a roof garden with nursery and swimming pool. A Second version was commissioned for Nantes, and he began work on what was to become one of his signature buildings – the chapel at Ronchamps.

This was a project designed to replace a simple church that had been destroyed by German bombs during the very last days of the war. It has become famous for its stark simplicity and its bizarre roof that has been described as ‘ a mix of partially crushed sombrero, a ram’s horn, and a bell-clapper’.

His wife continued to neglect her health, continued drinking, and eventually died in 1957. Shortly afterward Corbusier developed a multi-media installation for the Universal Exhibition at Brussels. This involved projected films and avant gard musical scores by Edward Varese and Iannis Xenakis, who at that time was working in Corbusier’s practice as an architect.

When his mother died at the age of ninety-nine, Corbusier had lost the two women underpinning his emotional life. He soldiered on alone, supported by a plethora of public accolades. He was showered with so many honorary degrees, he started turning them down.

Yet there continued to be professional frustrations and setbacks. Two major developments in Paris and New York came to nothing. In the face of these setbacks he fought back even more cantankerously than he had done before – until he eventually died doing what he had done all his adult life – swimming in the sea at his beloved gite at Roquebrune-cap-Martin.

Since then his longer term reputation as an architectural genius has been somewhat mixed. Open any architectural or interior design magazine today and you will see that his visual style is ubiquitous. The new norm is for minimalist decoration and open plan living. But some of his ideas on urbanisation now seem to smack dangerously of social engineering – and just as a by-the-way, the roofs on many of his buildings leaked.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Nicholas Fox Weber, Le Corbusier: A Life, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, pp.848, ISBN: 0375410430