documents, manifestos, and artistic policy statements

The tradition of constructivism began in Russia in 1920 following the Bolshevik revolution, as an attempt to define a new art for a new age and New Man. It spread to Germany, attaching itself to the Bauhaus movement, and then moved in the 1930s to France and Switzerland. In theory it continued after the second world war, but it was more evident in practice than in theoretical form, and it now finds modern reflections in the work of designers such as Neville Brody. The Tradition of Constructivism is a study of the entire moevement.

This collection of manifestos, articles, and agit-prop documents represents the theoretical and propagandist side of the movement – and it must be said that it captures well the exuberance and desire to create something new which erupted from artists such as Naum Gabo, Vladimir Tatlin, El Lissitzsky, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Editor Stephen Bann offers a prefatory essay, putting the documents into a historical context, and he supplies biographical notes to introduce each document, tracing the various intersections of the principle figures.

This collection of manifestos, articles, and agit-prop documents represents the theoretical and propagandist side of the movement – and it must be said that it captures well the exuberance and desire to create something new which erupted from artists such as Naum Gabo, Vladimir Tatlin, El Lissitzsky, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Editor Stephen Bann offers a prefatory essay, putting the documents into a historical context, and he supplies biographical notes to introduce each document, tracing the various intersections of the principle figures.

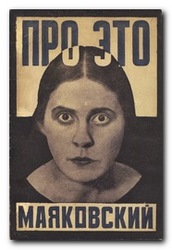

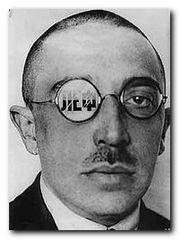

This was a movement which embraced many forms of art – painting, sculpture, typography, architecture, and photography – as well as what we would now call ‘mixed media’. The artists were keen to break with the romantic past, keen to embrace new technologies, new functionalism (useful art) and new abstractions. Many of them also held left-wing political views that harmonised well with the tenor of the early 1920s.

However, their theoretical writings are of a different order than the art works they produced. Many of their artistic manifestos and declarations of intent are couched in terribly abstract generalisations. Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner declare quite baldly in The Realistic Manifesto of 1920:

No new artistic system will withstand the pressure of a growing new culture until the very foundation of Art will be erected on the real laws of life.

And Alexei Gann is even more uncompromising in his proclamation Constructivism of 1922:

DEATH TO ART!

It arose NATURALLY

It developed NATURALLY

And disappeared NATURALLY

MARXISTS MUST WORK IN ORDER TO ELUCIDATE ITS DEATH SCIENTIFICALLY AND TO FORMULATE NEW PHENOMENA OF ARTISTIC LABOUR WITHIN THE NEW HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT OF OUR TIME.

Ironically, these radical attitudes gave the artists problems as soon as the official line in the Soviet Union changed abruptly from pro- to anti-modernism only a few years later under the rise of Stalin. It’s interesting to reflect that this form of argument in abstract generalisations, with no detailed examination of concrete examples, is precisely the rhetorical method which was to be used against these modernists by the apparatchicks of the Ministry of Culture from the late 1920s onwards.

The Zhdanhovs of this world didn’t sully their proclamations against ‘formalists’ and ‘decadents’ by anything so simple as the analysis of real works. For them, naming names or even just dropping hints was enough to send typographists, poets, and artists to the Gulag.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice.

This is a publication that is wonderfully rich in scholarly reference and support. There are full attributions for all the illustrations used, notes to the text, a huge bibliography, and full attributions for the sources of all the original documents reproduced. There are also some rather grainy black and white images of constructivist art, typography, and architecture which illustrate the fact that the imaginative products of these artists (irrespective of their sloganeering) was genuinely revolutionary.

Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

And occasionally nuggets of genuine insight emerge from all the generalizing dreck – as in Osip Brik’s observation regarding Rodchenko’s approach to constructivism:

The applied artist has nothing to do if he can’t embellish an object; for Rodchenko a complete lack of embellishment is a necessary condition for a proper construction of the object.

The documents span the period from the birth of constructivism in 1920 up to the post-war remnants of the movement. This is something of a special interest publication, but it’s well worth studying to understand the political and theoretical notions that provided the impetus behind an artistic endeavour which is still influential today. The theory might be dated, but constuctivist works of art are certainly not.

© Roy Johnson 2009

Stephen Bann (ed), The Tradition of Constructivism, Da Capo Press, 1990, pp.334, ISBN 0306803968

More on architecture

More on technology

More on design