short stories of fantasy, parody, mystery, and satire

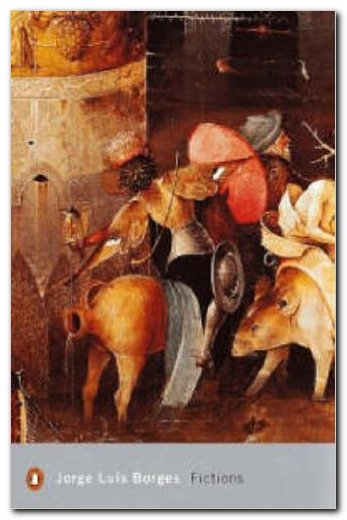

Fictions (1944) is a single-volume compilation of two collections of short stories which made Jorge Luis Borges famous – his 1941 publication The Garden of Forking Paths and the 1944 follow-up Artifices. He is one of the few writers to achieve international fame merely on the strength of short stories (Katherine Mansfield was another rare case).

His approach is distinctly playful. The stories are in the form of fantasies, essays on imaginary objects, fake biographies, bibliographic parodies, detective stories, and a form he is particularly fond of – commentaries on other people’s work, real and imaginary. He defends this approach in a typically witty manner:

It is a laborious madness and an impoverishing one, the madness of composing vast books — setting out in five hundred pages an idea that can be perfectly related orally in five minutes. The better way to go about it is to pretend that these books already exist, and offer a commentary on them.

This illustrates the ironic, tongue-in-cheek approach he brings to the short story form. He is also keen on blurring the distinction between fiction and reality. A story might begin by referring to the real world or a well known text, but he then blends it with fictional inventions or fanciful distortions which produce an effect like philosophic mind games. As a reader, you are suddenly no longer sure in which conceptual plane the narrative is taking place.

As a former librarian, he frequently highlights the bibliographic elements of his creations. He offers academic references (often spurious) for the sources of his information and bogus but amusing footnotes to support the authenticity of his narratives .

Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is a story in which Borges and his friend Bioy Casares (a real Argentinean writer) find one volume of an encyclopaedia that documents an imaginary world. It has been written by a collective of scholars working in secret. The language of this world has no nouns, there are no sciences, and one of the many schools of its philosophy denies the existence of time. The story has a postscript explaining how the project was later expanded to produce the invention of an entire planet. This at first appears to be a failure, but then physical objects from this imaginary world begin to appear in the fictional ‘present’.

In Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, a French belle-lettrist decides to re-write the whole of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, word for word from scratch. The story has an amusing defence that claims his reproduction (of which he only manages a couple of chapters) is more subtle than the original – because it was written three hundred years later. This conceit prefigures a school of literary criticism (Cultural Materialism) which argues that the meaning of a text is influenced both by the time in which it was produced as well as the time in which it is read.

In The Circular Ruins a man crawls into a primitive temple with the task of dreaming another person into being. He eventually manages it – first the heart, then the lungs, and so on. This being becomes his ‘son’, and he worries that his creation might come to realise that he is the projection of somebody else’s dream. When he tries to escape from this metaphysical problem, he suddenly realises that somebody else is dreaming him.

The Lottery of Babylon is a Kafka-like invention of a society run on pure chance, in which everyone is compelled to participate. Lots are drawn which might result in torture, death, or infinite riches. But even the administration of the results are subject to chance, and might be carried out at random, reversed, or simply ignored.

Another plot device favoured by Borges is the point of view reversal or the hidden narrator – such as the Irish republican in The Shape of the Sword who tells the story of how he saved the life of a coward during the civil war. He protects his comrade from his abject fear, only to find that the man has betrayed him to the Black and Tans. When the narrator is brought before a firing squad for execution the story turns itself inside out to reveal that the narrator is in fact the coward.

Funes, the Memorious is the potted biography of a poor young Argentinean boy who has a memory so prodigious that he cannot forget anything. As a child Ireneo Funes always knows exactly what time it is at any moment and can remember trivial events with chronological exactitude. He is thrown off a horse, crippled, and when he recovers he discovers that his memory is virtually infinite. He can remember the shape of clouds on any particular day, the pattern of the leaves on a tree, or the veins of decorative marbling in a book he has only seen once.

Whilst the stories are marvellously inventive, it has to be said that they are not uniformly consistent in quality. Some are formless and not much more than self-indulgent whimsy. But the best are tightly wrought and well constructed, with no superfluous material at all – just as a good short story should be. Borges went on to produce an enormously varied body of work – essays, poetry, translations, lectures, film and book reviews – in addition to his now-famous stories. But this collection Fictions remains what might be called his ‘signature’ work.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2015

Jorge Luis Borges, Fictions, London: Penguin Classics, 2000, pp.179, ISBN: 0141183845

Jorge Louis Borges links

![]() Borges Center – University of Pittsburgh

Borges Center – University of Pittsburgh

More on Jorge Luis Borges

Twentieth century literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories