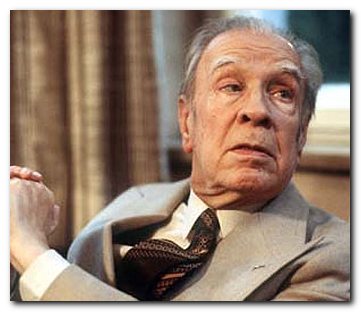

essayist, librarian, master of the modern short story

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) – full name Jorge Francisco Isodoro Luis Borges Acevedo – was born in Buenos Aires Argentina into an educated middle-class family. His father was a lawyer and a teacher of psychology who was part Spanish, part Portuguese, and half English. His mother was Uruguayan of Spanish descent. They lived in a lower-class suburb famous for its cabarets, brothels, knife fights and the tango.

He grew up in a house speaking both English and Spanish (as a child he thought they were the same language) and was he taught at home until he was eleven years old. The family lived in a large house with over one thousand volumes in English in its library. Despite the raffish nature of the neighbourhood, Borges reflected later in life that the two principal features of his childhood were his father’s library and a large garden – both of which feature prominently in his writing.

When he was only nine years old Borges translated Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince into Spanish, and it was published in a local journal. His friends all thought it was the work of his father.

In 1914 the family moved to Geneva, Switzerland where his father was seeking treatment for his failing eyesight. Borges attended school, learned French, read Carlyle in English, and began to study philosophy in German. The family travelled to Spain, and because of political unrest in Argentina at the time, decided to stay in Switzerland during the war.

Jorge Luis Borges received his baccalauréate from the College de Geneve in 1918. The family stayed in Europe after the war, living in Lugano, Barcelona, Majorca, Seville, and Madrid. Whilst in Spain Borges became attracted to the avant garde Ultraist literary movement inspired by Appolinaire and Marinetti. He also published his first poems.

In 1921 the family returned to Buenos Aires, where Borges published his first collection of poems Fervor de Buenos Aires (1923) a sixty-four page booklet paid for by his father and with a cover designed by his sister Norah. There was no profit made from this enterprise: he simply gave the book away to anybody who was interested. He produced journalism, essays, and book reviews, and contributed to the avant-garde review Martin Fierro.

The family returned to Switzerland in 1923 so that his father could resume treatment for his eyes, and when they returned to Argentina the following year, Borges discovered that he had developed a reputation as poet on the strength of his first book. In 1929 his book Cuaderno San Martin won a Municipal Prize, the prize money for which he spent on a complete set of Encyclopedia Britannica.

In 1931 Borges began publishing in the literary journal Sur established by Victoria Ocampo, which helped him to establish his literary reputation. He wrote works including parodies of detective stories with another Argentinean writer Adolfo Bioy Casares under the name H. Bustos Domecq. He also began to explore existential themes in his work, drawing a great deal of his inspiration not from his own personal life, but from his experience of literature.

He was appointed editor at the literary supplement of newspaper Critica in 1933 where he published works that were a blend of non-fictional essays and short stories. These were later collected under the title of A Universal History of Infamy (1936). The collection explored two types of writing. The first used a combination of the essay and the short story to tell what were really true stories. The second were literary spoofs or forgeries – texts which he passed off as translations of little-known works, but which were in fact his own inventions.

In 1935 he published the prototype of what is now considered a typical ‘Borgesian’ short story – ‘The Approach to Mu’tasim – a review of an imaginary novel. He had been influenced by his reading of Thomas Carlyle’s Sator Resartus, a book comprised of reflections on the work and life of an imaginary German philosopher. It is a mark of Borges preference for shorter literary genres (and what he jokingly called his ‘laziness’) that rather than creating complete imaginary works, he thought it was more inventive to conjure up their existence by writing reviews of them as if they actually existed.

Between 1936 and 1939 he wrote a weekly column for El Hogar, and in 1939 found work as an assistant in the Buenos Aires Municipal Library. His duties were so light he could complete them in the first hour. He spent the rest of the day in the basement, writing and translating the work of Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner into Spanish. His first volume of short stories The Garden of Forking Paths (1941) collected work he had previously published in Sur.

His eyesight began to fade in the late 1930s and, unable to support himself as a writer, he began giving public lectures. He lived with his widowed mother, who became his personal secretary. Although he relied a great deal on his imaginative responses to literature, he never learned to read Braille. He became completely blind by the late 1950s.

When Juan Peron came to power in 1946 Borges was ‘promoted’ to the job of Inspector of Rabbits and Poultry in the Public Markets, a post from which he immediately resigned. He was elected to the presidency of the Argentine Writer’s Society in 1950 and given the job of director of the National Library in 1955, even though he was by that time completely blind.

Some of his work was translated into English during the 1940s and 1950s, but his international reputation dates from the early 1960s when he was awarded the International Publisher’s Prize, the Prix Formentor – which he shared with Samuel Beckett. He was appointed for a year to the Chair of literature at the University of Texas at Austin, and went on to give lecture tours in America and Europe.

Two major anthologies of his work were published in 1962 – Ficciones and Layrinths – which further enhanced his international reputation. In 1967 Borges embarked on a five year period of collaboration with the American translator Norman Thomas di Giovanni which helped to make his work better known in the English-speaking world.

Then in 1967 Jorge Luis Borges married an old friend Elsa Astete Millan who had become a widow, but the marriage only lasted three years. Borges went back to his mother, with whom he lived until her death at the age of almost one hundred. He travelled extensively on lecture tours, and published further collections of his work – The Book of Sand, Dr Brodie’s report, and The Book of Imaginary Beings.

In 1986, a few months before his death, he married his literary assistant Maria Kodama, who thereby gained control of his literary estate and the considerable income from it. Despite international protests, she rescinded all publishing rights for the existing collections of his work and commissioned new translations.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Jorge Luis Borges

Twentieth century literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories