tutorial, textual history, study resources, and web links

Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) is Lawrence’s most controversial novel, and perhaps the first serious work of literature to explore human sexuality in explicit detail. It features some of his most lyrical and poetic prose style alongside the theme of class conflict – acted out between the aristocratic Constance Chatterley, and her gamekeeper-lover Mellors. Some feminist critics now claim the novel to be deeply misogynistic, because part of its argument is that women will reach true fulfillment only by submitting themselves to men. Lawrence wrote the novel three times, and it made important historical impacts twice over: one when it was first published in 1928, and the second in the famous obscenity trial in 1960.

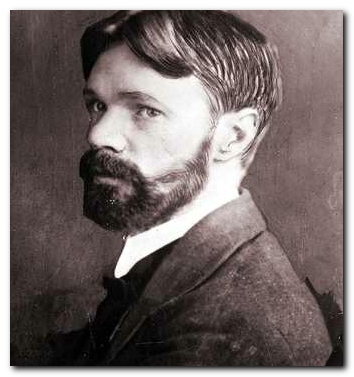

D.H.Lawrence

D.H. Lawrence is a writer who excites great passions in his readers – which is entirely appropriate, since that is how he wrote. He is the first really great writer to come from the (more or less) working class, and much of his work deals with issues of class, as well as other fundamentals such as the relationships between men, women, and the natural world.

At times he becomes mystic and visionary, and his prose style can be poetic, didactic, symbolic, and bombastic all within the space of a few pages. He also deals with issues of sexuality and politics in a manner which is often controversial.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – textual history

There were in fact three different versions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The first, written in 1926, is now known as The First Lady Chatterley. Its main focus is on social and political aspects of a mining community, and it has none of the explicit sex scenes or the frank language for which the third version became famous. The first version was not published until 1944.

The second version was called, rather coyly, John Thomas and Lady Jane. The relationship between Constance Chatterley and her gamekeeper (then called Oliver Parkin) is treated in a more gentle manner. Indeed, Lawrence had Tenderness as an alternative title. It was first published in an Italian translation by Mondadori in 1954.

When he finished the third version in 1928 Lawrence encountered immediate opposition to its publication – both by his agents and his publishers. Nobody would touch the book unless he made substantial cuts – which he refused to make. Lawrence was a veteran of battles with publishers and censors, but he believed very passionately that writers should be free to express themselves openly about matters which they believed to be important and true.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

The novel quickly developed a scandalous reputation, both because of its explicit sexual scenes and because of Lawrence’s (very occasional) use of words such as cunt and fuck which were regarded as completely taboo terms at the time. Lawrence did indeed make money out of the venture, which he shrewdly put into successful investments on the New York Stock Exchange. But two things conspired against him making even more.

Because the book had been privately published, it was not formally copyrighted, and because of its reputation many other printers and publishers issued pirated copies, which sold well and made them, but not Lawrence, healthy profits. The book was pirated on both sides of the Atlantic.

In response to this, Lawrence put forth a second edition in November 1928, again from the tiny Florentine print shop, and then a cheap edition in May 1929 of 3,000 copies in Paris. This edition sold out by August at sixty francs and was the first to include his prefatory essay entitled ‘My Skirmish with Jolly Roger’. This was a defense, explication, and history of the novel that was published posthumously as A Propos of Lady Chatterly’s Lover.

Lawrence became extremely ill in late 1929 and moved to the Swiss Alps and then to the South of France, where he died in 1930. With the death of Lawrence, publishers felt at liberty to expurgate the novel at will. Without a copyright, a publisher who could come up with a clean version had the promise of the novel’s preceding reputation to back up its success.

In 1932, two expurgated versions were published, 2,000 copies in America and 3,440 copies in England. The publishers of this version euphemistically referred to it as an `abridged’ edition. Whole pages were left out with nothing but confusing asterisks left to mark their omissions. There was no consistency in the use of these astriks; some deleted pages were not even mentioned. Every description of the act of sex and all four-letter words which could have been remotely objectional were left out.

The National Union Catalog records fifteen different printings of expurgated versions between the years 1932 and 1943 in America, England, and Paris. A considerable number of these novels were sold, and the black market still carried a full line of assorted unexpurgated copies. The novel continued to have an underground existence and a high reputation as a banned or forbidden work in the post-war years.

When the full unexpurgated edition was published in Britain in 1960, the trial of the publishers, Penguin Books, under the Obscene Publications Act of 1959 was a major public event and a test of the new obscenity law. The 1959 act, introduced by Roy Jenkins, had made it possible for publishers to escape conviction if they could show that a work was of literary merit. One of the objections was for the frequent use of the word ‘fuck’ and its derivatives.

Various academic critics, including E. M. Forster, Helen Gardner and Raymond Williams, were called as witnesses, and the verdict, delivered on November 2, 1960, was not guilty. This resulted in a far greater degree of freedom for publishing explicit material in the UK. The prosecution was ridiculed for being out of touch with changing social norms when the chief prosecutor, Mervyn Griffith-Jones, asked if it was the kind of book ‘you would wish your wife or servants to read’.

[With thanks to Randall Martin.]

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – study resources

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – annotated Kindle eBook edition

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – annotated Kindle eBook edition

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Signet Classics – Amazon UK

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Signet Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Signet Classics – Amazon US

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Signet Classics – Amazon US

![]() The First Lady Chatterley’s Lover – first version – Amazon UK

The First Lady Chatterley’s Lover – first version – Amazon UK

![]() The Second Lady Chatterley’s Lover – second version – Amazon UK

The Second Lady Chatterley’s Lover – second version – Amazon UK

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – plain text edition at Project Gutenberg

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – plain text edition at Project Gutenberg

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – audioBook on CD – Amazon UK

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – audioBook on CD – Amazon UK

![]() Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Cambridge scholarly edition – Amazon UK

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – Cambridge scholarly edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Critical Guide to D.H. Lawrence – Amazon UK

The Complete Critical Guide to D.H. Lawrence – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to D.H.Lawrence – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to D.H.Lawrence – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Short Novels of D.H.Lawrence – Amazon UK

The Complete Short Novels of D.H.Lawrence – Amazon UK

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – plot summary

Connie Reid is raised as a cultured bohemian of the upper-middle class, and is introduced to love affairs – intellectual and sexual liaisons – as a teenager. In 1917, at 23, she marries Clifford Chatterley, the scion of an aristocratic line. After a month’s honeymoon, he is sent to war, and returns impotent, paralyzed from the waist down.

After the war, Clifford becomes a successful writer, and many intellectuals flock to the Chatterley mansion at Wragby Hall. Connie feels isolated; the intellectuals she meets prove empty and bloodless, and she resorts to a brief and dissatisfying affair with a visiting playwright, Michaelis.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Into the void of Connie’s life comes Oliver Mellors, the gamekeeper on Clifford’s estate, newly returned from serving in the army. Mellors is aloof and derisive, and yet Connie feels curiously drawn to him by his innate nobility and grace, his purposeful isolation, his undercurrents of natural sensuality.

After several chance meetings in which Mellors keeps her at arm’s length, reminding her of the class distance between them, they meet by chance at a hut in the forest, where they have sex. This happens on several occasions, but still Connie feels a distance between them, remaining profoundly separate from him despite their physical closeness.

One day, Connie and Mellors meet by coincidence in the woods, and they have sex on the forest floor. This time, they experience simultaneous orgasms. This is a revelatory and profoundly moving experience for Connie; she begins to adore Mellors, feeling that they have connected on some deep sensual level. She is proud to believe that she is pregnant with Mellors’ child. He is a real, ‘living’ man, as opposed to the emotionally dead intellectuals and the dehumanized industrial workers. They grow progressively closer, connecting on a primordial physical level, as woman and man rather than as two minds or intellects.

Connie goes away to Venice for a vacation. While she is gone, Mellors’ old wife returns, causing a scandal. Connie returns to find that Mellors has been fired as a result of the negative rumors spread about him by his resentful wife, against whom he has initiated divorce proceedings. Connie admits to Clifford that she is pregnant with Mellors’ baby, but Clifford refuses to give her a divorce. The novel ends with Mellors working on a farm, waiting for his divorce, and Connie living with her sister, also waiting.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – principal characters

| Clifford Chatterley | landowner, disabled WW1 veteran, and businessman |

| Constance Chatterley | his wife, an intellectual and social progressive |

| Oliver Mellors | ex-soldier, ex-blacksmith, intellectual, and the gamekeeper at Wragby Hall |

| Mrs (Ivy) Bolton | Clifford’s devoted housekeeper |

| Michaelis | successful Irish playwright |

| Sir Macolm Reid | Connie’s father, a painter |

| Hilda Reid | Connie’s sister |

| Tommy Dukes | an intellectual friend of Clifford’s |

| Duncan Forbes | an artist friend of Connie and Hilda |

| Bertha Coutts | Mellor’s wife – who does no appear in the novel |

Film version

2007 French adaptation of the second version of the novel

![]() See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

Further reading

Biography

![]() Frieda Lawrence, Not I, But the Wind…, New York: Viking Press, 1934.

Frieda Lawrence, Not I, But the Wind…, New York: Viking Press, 1934.

![]() Harry T. Moore, The Life and Works of D.H. Lawrence, London: Unwin Books, 1951.

Harry T. Moore, The Life and Works of D.H. Lawrence, London: Unwin Books, 1951.

![]() Keith Sagar, The Life of D.H.Lawrence: An Illustrated Biography, London: Eyre Methuen, 1980.

Keith Sagar, The Life of D.H.Lawrence: An Illustrated Biography, London: Eyre Methuen, 1980.

![]() John Worthen, D.H.Lawrence: The Early Years: 1885-1912: The Cambridge Biography of D.H. Lawrence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

John Worthen, D.H.Lawrence: The Early Years: 1885-1912: The Cambridge Biography of D.H. Lawrence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Brenda Maddox, The Married Man: A Biography of D.H.Lawrence, London: Sinclair Stevenson, 1994.

Brenda Maddox, The Married Man: A Biography of D.H.Lawrence, London: Sinclair Stevenson, 1994.

Letters

![]() J.T. Boulton (ed), The Selected Letters of D.H. Lawrence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

J.T. Boulton (ed), The Selected Letters of D.H. Lawrence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Criticism

![]() David Ellis, D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’: A Casebook, Oxford University Press, 2006.

David Ellis, D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’: A Casebook, Oxford University Press, 2006.

![]() John Worthen, The First ‘Women in Love’ (Cambridge Edition of the Works of D.HLawrence), Cambridge University Press, 2002.

John Worthen, The First ‘Women in Love’ (Cambridge Edition of the Works of D.HLawrence), Cambridge University Press, 2002.

![]() Graham Handley, Brodie’s Notes on D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’, London: Macmillan, 1992.

Graham Handley, Brodie’s Notes on D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’, London: Macmillan, 1992.

![]() Harold Bloom, D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’ (Modern Critical Interpretations), Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom, D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’ (Modern Critical Interpretations), Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Anne Fernihough, The Cambridge Companion to D.H.Lawrence, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Anne Fernihough, The Cambridge Companion to D.H.Lawrence, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Fiona Becket, The Complete Critical Guide to D.H. Lawrence, London: Routledge, 2002.

Fiona Becket, The Complete Critical Guide to D.H. Lawrence, London: Routledge, 2002.

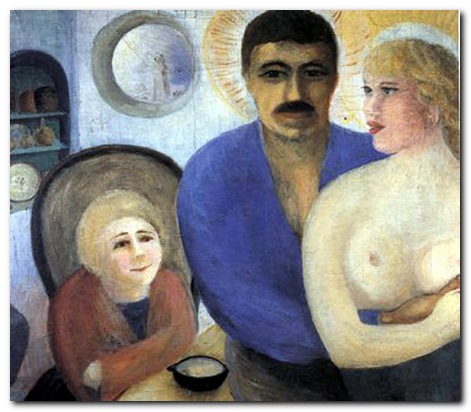

Painting by Lawrence – ‘The Holy Family’

Background reading

![]() Mary Freeman, D.H.Lawrence A Basic Study of His Ideas, Grosset and Dunlap, 1955.

Mary Freeman, D.H.Lawrence A Basic Study of His Ideas, Grosset and Dunlap, 1955.

![]() F.R.Leavis, D.H.Lawrence: Novelist, London: Chatto and Windus, 1955.

F.R.Leavis, D.H.Lawrence: Novelist, London: Chatto and Windus, 1955.

![]() Mark Spilka, The Love Ethic of D.H.Lawrence, Dobson, 1955.

Mark Spilka, The Love Ethic of D.H.Lawrence, Dobson, 1955.

![]() Graham Hough, The Dark Sun: A Study of D.H.Lawrence, New York: Capricorn Books, 1956.

Graham Hough, The Dark Sun: A Study of D.H.Lawrence, New York: Capricorn Books, 1956.

![]() Eliseo Vivas, D.H.Lawrence: The Failure and the Triumph of Art, General Books 1960.

Eliseo Vivas, D.H.Lawrence: The Failure and the Triumph of Art, General Books 1960.

![]() Kingsley Widmer, The Art of Perversity: D.H.Lawrence’s Shorter Fiction, University of Washington Press, 1962.

Kingsley Widmer, The Art of Perversity: D.H.Lawrence’s Shorter Fiction, University of Washington Press, 1962.

![]() Eugene Goodheart, The Utopian Vision of D.H.Lawrence, Transaction Publishers, 1963.

Eugene Goodheart, The Utopian Vision of D.H.Lawrence, Transaction Publishers, 1963.

![]() Julian Moynahan, The Deed of Life: The Novels and Tales of D.H.Lawrence, Oxford University Press, 1963.

Julian Moynahan, The Deed of Life: The Novels and Tales of D.H.Lawrence, Oxford University Press, 1963.

![]() George Panichas, Adventure in Consciousness: Lawrence’s Religious Quest, Folcroft Library Editions, 1964.

George Panichas, Adventure in Consciousness: Lawrence’s Religious Quest, Folcroft Library Editions, 1964.

![]() Helen Corke, D.H. Lawrence: The Croydon Years, Austin (Tex): University of Texas Press, 1965.

Helen Corke, D.H. Lawrence: The Croydon Years, Austin (Tex): University of Texas Press, 1965.

![]() George Ford, Double Measure; A Study of D.H.Lawrence, New York: Holt Reinhart and Winston, 1965.

George Ford, Double Measure; A Study of D.H.Lawrence, New York: Holt Reinhart and Winston, 1965.

![]() H M Daleski, The Forked Flame: A Study of D.H.Lawrence, Evanston (Ill): Northwestern University Press, 1965.

H M Daleski, The Forked Flame: A Study of D.H.Lawrence, Evanston (Ill): Northwestern University Press, 1965.

![]() Keith Sagar, The Art of D.H.Lawrence, Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Keith Sagar, The Art of D.H.Lawrence, Cambridge University Press, 1966.

![]() David Cavitch, D.H.Lawrence and the New World, Oxford University Press, 1969.

David Cavitch, D.H.Lawrence and the New World, Oxford University Press, 1969.

![]() Colin Clarke, River of Dissolution: D.H.Lawrence and English Romanticism, London: Routledge, 1969.

Colin Clarke, River of Dissolution: D.H.Lawrence and English Romanticism, London: Routledge, 1969.

![]() Baruch Hochman, Another Ego: Self and Society in D.H.Lawrence, University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

Baruch Hochman, Another Ego: Self and Society in D.H.Lawrence, University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

![]() Keith Aldritt, The Visual Imagination of D.H.Lawrence, Hodder and Stoughton, 1971.

Keith Aldritt, The Visual Imagination of D.H.Lawrence, Hodder and Stoughton, 1971.

![]() R E Pritchard, D.H.Lawrence: Body of Darkness, Hutchinson, 1971.

R E Pritchard, D.H.Lawrence: Body of Darkness, Hutchinson, 1971.

![]() John E Stoll, The Novels of D.H.Lawrence: A Search for Integration, University of Missouri Press, 1971.

John E Stoll, The Novels of D.H.Lawrence: A Search for Integration, University of Missouri Press, 1971.

![]() Frank Kermode, D.H. Lawrence, London: Fontana, 1973.

Frank Kermode, D.H. Lawrence, London: Fontana, 1973.

![]() Scott Sanders, D.H.Lawrence: The World of the Major Novels, Vision Press, 1973.

Scott Sanders, D.H.Lawrence: The World of the Major Novels, Vision Press, 1973.

![]() F.R.Leavis, Thought, Words, and Creativity: Art and Thought in Lawrence, Chatto and Windus, 1976.

F.R.Leavis, Thought, Words, and Creativity: Art and Thought in Lawrence, Chatto and Windus, 1976.

![]() Marguerite Beede Howe, The Art of the Self in D.H.Lawrence, Ohio University Press, 1977.

Marguerite Beede Howe, The Art of the Self in D.H.Lawrence, Ohio University Press, 1977.

![]() Alastair Niven, D.H.Lawrence: The Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Alastair Niven, D.H.Lawrence: The Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Anne Smith, Lawrence and Women, London: Vision Press, 1978.

Anne Smith, Lawrence and Women, London: Vision Press, 1978.

![]() R.P. Draper (ed), D.H. Lawrence: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1979.

R.P. Draper (ed), D.H. Lawrence: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1979.

![]() John Worthen, D.H.Lawrence and the Idea of the Novel, London: Macmillan, 1979.

John Worthen, D.H.Lawrence and the Idea of the Novel, London: Macmillan, 1979.

![]() Aidan Burns, Nature and Culture in D.H.Lawrence, London: Macmillan, 1980.

Aidan Burns, Nature and Culture in D.H.Lawrence, London: Macmillan, 1980.

![]() L D Clark, The Minoan Distance: Symbolism of Travel in D.H.Lawrence, University of Arizona Press, 1980.

L D Clark, The Minoan Distance: Symbolism of Travel in D.H.Lawrence, University of Arizona Press, 1980.

![]() Roger Ebbatson, D.H.Lawrence and the Nature Tradition: A Theme in English Fiction 1859-1914, Humanities Oress, 1980.

Roger Ebbatson, D.H.Lawrence and the Nature Tradition: A Theme in English Fiction 1859-1914, Humanities Oress, 1980.

![]() Alastair Niven, D.H.Lawrence: The Writer and His Work, New York: Scribner, 1980.

Alastair Niven, D.H.Lawrence: The Writer and His Work, New York: Scribner, 1980.

![]() Philip Hobsbaum, A Reader’s Guide to D.H.Lawrence, Thames and Hudson, 1981.

Philip Hobsbaum, A Reader’s Guide to D.H.Lawrence, Thames and Hudson, 1981.

![]() Kim A.Herzinger , D.H.Lawrence in His Time: 1908-1915, Bucknell University Press, 1982.

Kim A.Herzinger , D.H.Lawrence in His Time: 1908-1915, Bucknell University Press, 1982.

![]() Graham Holderness, D.H.Lawrence: History, Ideology and Fiction, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1982.

Graham Holderness, D.H.Lawrence: History, Ideology and Fiction, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1982.

![]() Hilary Simpson, D.H.Lawrence and Feminism, London: Croom Helm, 1982.

Hilary Simpson, D.H.Lawrence and Feminism, London: Croom Helm, 1982.

![]() Gamini Salgado, A Preface to D.H. Lawrence, London: Longman, 1983.

Gamini Salgado, A Preface to D.H. Lawrence, London: Longman, 1983.

![]() Judith Ruderman, D.H.Lawrence and the Devouring Mother, Duke University Press, 1984.

Judith Ruderman, D.H.Lawrence and the Devouring Mother, Duke University Press, 1984.

![]() Anthony Burgess, Flame Into Being: The Life and Work of D.H.Lawrence, London: Heinemann, 1985.

Anthony Burgess, Flame Into Being: The Life and Work of D.H.Lawrence, London: Heinemann, 1985.

![]() Sheila McLeod, Lawrence’s Men and Women, London: Heinemann, 1985.

Sheila McLeod, Lawrence’s Men and Women, London: Heinemann, 1985.

![]() Henry Miller, The World of Lawrence: A Passionate Appreciation, London: Calder Publications, [1930] 1985.

Henry Miller, The World of Lawrence: A Passionate Appreciation, London: Calder Publications, [1930] 1985.

![]() Keith Sagar, D.H.Lawrence: Life Into Art, London: Penguin Books, 1985.

Keith Sagar, D.H.Lawrence: Life Into Art, London: Penguin Books, 1985.

![]() Mara Kalnins (ed), D.H. Lawrence: Centenary Essays, Bristol: Classical Press, 1986.

Mara Kalnins (ed), D.H. Lawrence: Centenary Essays, Bristol: Classical Press, 1986.

![]() Michael Black, D.H. Lawrence: The Early Fiction, Cambridge University Press, 1986

Michael Black, D.H. Lawrence: The Early Fiction, Cambridge University Press, 1986

![]() Peter Scheckner, Class, Politics, and the Individual: A Study of the Major Works of D.H.Lawrence, Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1986.

Peter Scheckner, Class, Politics, and the Individual: A Study of the Major Works of D.H.Lawrence, Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1986.

![]() Cornelia Nixon, D.H.Lawrence’s Leadership Novels and the Turn Against Women, University of California Press, 1986.

Cornelia Nixon, D.H.Lawrence’s Leadership Novels and the Turn Against Women, University of California Press, 1986.

![]() Colin Milton, Lawrence and Nietzsche: A Study in Influence, Mercat Press, 1988.

Colin Milton, Lawrence and Nietzsche: A Study in Influence, Mercat Press, 1988.

![]() Peter Balbert, D.H.Lawrence and the Phallic Imagination: Essays on Sexual Identity and Feminist Misreading, London: Macmillan, 1989.

Peter Balbert, D.H.Lawrence and the Phallic Imagination: Essays on Sexual Identity and Feminist Misreading, London: Macmillan, 1989.

![]() Wayne Templeton, States of Estrangement: the Novels of D.H.Lawrence 1912-17, Whiston Publishing, 1989.

Wayne Templeton, States of Estrangement: the Novels of D.H.Lawrence 1912-17, Whiston Publishing, 1989.

![]() Janet Barron, D.H.Lawrence: (Feminist Readings), Prentice Hall, 1990.

Janet Barron, D.H.Lawrence: (Feminist Readings), Prentice Hall, 1990.

![]() Keith Brown (ed), Rethinking Lawrence, Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1990.

Keith Brown (ed), Rethinking Lawrence, Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1990.

![]() James C Cowan, D.H.Lawrence and the Trembling Balance, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1990.

James C Cowan, D.H.Lawrence and the Trembling Balance, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1990.

![]() John B Humma, Metaphor and Meaning in D.H.Lawrence’s Later Novels, University of Missouri Press 1990.

John B Humma, Metaphor and Meaning in D.H.Lawrence’s Later Novels, University of Missouri Press 1990.

![]() G M Hyde, D.H.Lawrence (Modern Novelists), London: Macmillan, 1990.

G M Hyde, D.H.Lawrence (Modern Novelists), London: Macmillan, 1990.

![]() Allan Ingram, The Language of D.H. Lawrence, London: Macmillan, 1990.

Allan Ingram, The Language of D.H. Lawrence, London: Macmillan, 1990.

![]() Nancy Kushigian, Pictures and Fictions: Visual Modernism and the Pre-War Novels of D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1990.

Nancy Kushigian, Pictures and Fictions: Visual Modernism and the Pre-War Novels of D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1990.

![]() Tony Pinkney, Lawrence (New Readings), Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Weatsheaf, 1990.

Tony Pinkney, Lawrence (New Readings), Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Weatsheaf, 1990.

![]() Leo J.Dorisach, Sexually Balanced Relationships in the Novels of D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1991.

Leo J.Dorisach, Sexually Balanced Relationships in the Novels of D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1991.

![]() Nigel Kelsey, D.H.Lawrence: Sexual Crisis (Studies in 20th Century Literature), London: Macmillan, 1991.

Nigel Kelsey, D.H.Lawrence: Sexual Crisis (Studies in 20th Century Literature), London: Macmillan, 1991.

![]() Barbara Mensch, D.H.Lawrence and the Authoritarian Personality, London: Macmillan, 1991.

Barbara Mensch, D.H.Lawrence and the Authoritarian Personality, London: Macmillan, 1991.

![]() John Worthen, D H Lawrence (Modern Fiction), London: Arnold, 1991.

John Worthen, D H Lawrence (Modern Fiction), London: Arnold, 1991.

![]() Michael Bell, D.H.Lawrence: Language and Being, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Michael Bell, D.H.Lawrence: Language and Being, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

![]() Michael Black, D.H. Lawrence: Sons and Lovers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Michael Black, D.H. Lawrence: Sons and Lovers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

![]() Virginia Hyde, The Risen Adam: D. H. Lawrence’s Revisionist Typology, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992.

Virginia Hyde, The Risen Adam: D. H. Lawrence’s Revisionist Typology, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992.

![]() James B.Sipple, Passionate Form: life process as artistic paradigm in D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1992.

James B.Sipple, Passionate Form: life process as artistic paradigm in D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1992.

![]() Kingsley Widmer, Defiant Desire: Some Dialectical Legacies of D.H.Lawrence, Southern Illinois University Press, 1992.

Kingsley Widmer, Defiant Desire: Some Dialectical Legacies of D.H.Lawrence, Southern Illinois University Press, 1992.

![]() Anne Fernihough, D.H.Lawrence: Aesthetics and Ideology, Clarendon Press, 1993.

Anne Fernihough, D.H.Lawrence: Aesthetics and Ideology, Clarendon Press, 1993.

![]() Linda R Williams, Sex in the Head: Visions of Femininity and Film in D.H.Lawrence, Prentice Hall, 1993.

Linda R Williams, Sex in the Head: Visions of Femininity and Film in D.H.Lawrence, Prentice Hall, 1993.

![]() Katherine Waltenscheid, The Resurrection of the Body: Touch in D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1993.

Katherine Waltenscheid, The Resurrection of the Body: Touch in D.H.Lawrence, Peter Lang Publishing, 1993.

![]() Robert E.Montgomery, The Visionary D.H.Lawrence: Beyond Philosophy and Art, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Robert E.Montgomery, The Visionary D.H.Lawrence: Beyond Philosophy and Art, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

![]() Leo Hamalian, D.H.Lawrence and Nine Women Writers, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996.

Leo Hamalian, D.H.Lawrence and Nine Women Writers, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996.

![]() Anne Fernihough, The Cambridge Companion to D.H.Lawrence, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Anne Fernihough, The Cambridge Companion to D.H.Lawrence, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

![]() Fiona Becket, The Complete Critical Guide to D.H.Lawrence, London: Routledge, 2002.

Fiona Becket, The Complete Critical Guide to D.H.Lawrence, London: Routledge, 2002.

![]() James C Cowan, D.H. Lawrence: Self and Sexuality, Ohio State University Press, 2003.

James C Cowan, D.H. Lawrence: Self and Sexuality, Ohio State University Press, 2003.

![]() John Worthen, D.H.Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider, London: Penguin, 2006.

John Worthen, D.H.Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider, London: Penguin, 2006.

![]() David Ellis (ed), D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’: A Casebook, Oxford University Press, 2006.

David Ellis (ed), D.H.Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’: A Casebook, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Other work by D.H.Lawrence

Sons and Lovers This is Lawrence’s first great novel. It’s a quasi-autobiographical account of a young man’s coming of age in the early years of the twentieth century. The setting is working class Nottinghamshire, and the story it focuses on class conflicts and gender issues as young Paul Morrell is torn between a passionate relationship with his mother and his attraction to other women. He is also locked insomething of an Oedipal struggle with his coal-miner father. If you are new to Lawrence and his work, this is a good place to start.

Sons and Lovers This is Lawrence’s first great novel. It’s a quasi-autobiographical account of a young man’s coming of age in the early years of the twentieth century. The setting is working class Nottinghamshire, and the story it focuses on class conflicts and gender issues as young Paul Morrell is torn between a passionate relationship with his mother and his attraction to other women. He is also locked insomething of an Oedipal struggle with his coal-miner father. If you are new to Lawrence and his work, this is a good place to start.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Women in Love begins where his previous big novel The Rainbow leaves off and features the Brangwen sisters as they try to forge new types of liberated personal relationships. The men they choose are trying to do the same thing – and the results are problematic and often disturbing for all concerned. Many regard this as his finest novel, where his ideas are matched with passages of superb writing. The locations combine urban Bohemia with a symbolic climax which takes place in the icy snow caps of the Alps.

Women in Love begins where his previous big novel The Rainbow leaves off and features the Brangwen sisters as they try to forge new types of liberated personal relationships. The men they choose are trying to do the same thing – and the results are problematic and often disturbing for all concerned. Many regard this as his finest novel, where his ideas are matched with passages of superb writing. The locations combine urban Bohemia with a symbolic climax which takes place in the icy snow caps of the Alps.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

D.H.Lawrence – web links

![]() D.H.Lawrence at Mantex

D.H.Lawrence at Mantex

Biographical notes, book reviews, study guides, videos, bibliographies, critical studies, and web links.

![]() D.H.Lawrence at Project Gutenberg

D.H.Lawrence at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts of the novels, stories, travel writing, and poetry – available in a variety of formats.

![]() D.H.Lawrence at Wikipedia

D.H.Lawrence at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, publishing history, the Lady Chatterley trial, critical reputation, bibliography, archives, and web links.

![]() D.H.Lawrence at the Internet Movie Database

D.H.Lawrence at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of Lawrence’s work for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production, box office, trivia, and even quizzes.

![]() D.H.Lawrence archive at the University of Nottingham

D.H.Lawrence archive at the University of Nottingham

Biography, further reading, textual genetics, frequently asked questions, his local reputation, research centre, bibliographies, and lists of holdings.

![]() D.H.Lawrence and Eastwood

D.H.Lawrence and Eastwood

Nottinhamshire local enthusiast web site featuring biography, historical and recent photographs of the Eastwood area and places associated with Lawrence.

![]() The World of D.H.Lawrence

The World of D.H.Lawrence

Yet another University of Nottingham web site featuring biography, interactive timeline, maps, virtual tour, photographs, and web links.

![]() D.H.Lawrence Heritage

D.H.Lawrence Heritage

Local authority style web site, with maps, educational centre, and details of lectures, visits, and forthcoming events.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on D.H. Lawrence

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories