poetry, academic gossip, sex, equivocation, and death

Philip Larkin first met Monica Jones at University College Leicester in the autumn of 1946 when they were both twenty-four. He was the newly appointed Assistant Librarian and she was a Lecturer in English. In 1950 he moved to Belfast, and then on to Hull, while she remained at Leicester. She started as a correspondent and friend, became his lover and confidante, and spent forty ears as his sometime muse and psychic nursemaid until his sudden death in 1985.

This is a selection from the almost two thousand letters he wrote to her – though he wrote double that number to his mother. Unfortunately, her side of the correspondence is embargoed in the Bodleian Library until 2035.

They were rather an oddly matched couple. He was shy, reserved, and socially very conservative. She was a flamboyant blonde who was given to wearing short skirts, fishnet tights (sometimes with holes) and high-heeled shoes. He was assiduous in his attitude to work (even though he didn’t like it): she on the other hand never published a word in her whole career as a university lecturer

They were rather an oddly matched couple. He was shy, reserved, and socially very conservative. She was a flamboyant blonde who was given to wearing short skirts, fishnet tights (sometimes with holes) and high-heeled shoes. He was assiduous in his attitude to work (even though he didn’t like it): she on the other hand never published a word in her whole career as a university lecturer

The letters begin as Larkin, newly appointed as assistant librarian at Queens University Belfast, is seeking estimates for a privately printed edition of his poems. Given his later fame, this is a salutary lesson for any would-be writers. He also begins what was to become a long series of equivocations when setting up meetings with Monica.

They tested the temperature of the other’s enthusiasm from the tone and content of their letters. Yet his hesitation and contradictions regarding their planned assignations are amusingly reminiscent of Kafka. Timetables, routes, hotels, and dates are discussed in excruciating detail, potential excuses for a no-show are set up in advance, and penny-pinching attention to the cost are flagged up in a clear display of his ambivalence about the relationship.

Larkin’s complex romantic life is now quite well known, but what the letters reveal is very much a meeting of minds. They had similar literary tastes and similar isolationist tendencies – though the editor of this volume Anthony Thwaite puts it differently, saying that “e;they fed each other’s misery”e;.

Larkin comes across as breathtakingly pompous and arrogant when lecturing Monica on how she should modify her style of conversation – though it should be said that first-hand accounts report her as hectoring people in general, and paying no attention to what they said in reply – which were precisely his criticisms.

There are persistent complaints and self-criticism about his lack of productivity, and yet sadly thirty volumes of his personal diaries were destroyed after his death. The request was his own; it was enacted by Monica as his literary executor; and the journals were shredded in Hull library by his secretary.

There is an enormous amount of moaning, complaints about illnesses (real and imaginary), disgust at his own ineffectuality, and endless reasons for not getting married, which Monica was clearly expecting him to propose. Indecision and a stolid bachelor inertia dogged his every step. In one single letter he goes into a rage about the noise from a neighbour’s radio, then turns down the opportunity of renting a spacious flat because it would be too big and ‘No sound would ever have penetrated its walls’.

The year 1955 should have been a high point in his life: he had secured the job at Hull on a good salary (£1,500 pa) and the first volume of his poems was being published to some acclaim. Yet his letters are full of self-loathing and despair:

I do feel absolutely sick at heart, my blankness has been goaded into revulsion & I am up in arms again, sufficiently fed up to start moving [address] again, back at the point when not moving is worse than moving. And I can’t do anything, not now: I must endure the weekend, & all next week, & … This state of mind is different than my earlier howls: this is a kind of nausea, as if life were some milk-skin clinging to my lip. I don’t, at the moment, see how I am going to endure it, it’s all so frightful

This is the sort of volitional paralysis and neurasthenia (to say nothing of the hypochondria) which reinforces the comparison with Kafka – another literary bachelor who was riven by contradictions, moved from one set of rented lodgings to another, and agonized endlessly about his fear of marriage.

What makes the letters bearable and very entertaining amidst all the misery is their fluidity and inventiveness, his gossipy wit, adoption of comic personae, abrupt variations in register, his heterogeneous topics, and his cultivated intelligence.

Larkin is voracious in his reading and not at all snobbish in taste – everything from renaissance poetry to contemporary fiction. He championed Barbara Pym and helped to restore her reputation. His essential favourites are classics, and his enthusiastic notes on Bleak Housemake you feel like reading it again, as do his observations and deep feelings for Hardy’s poetry.

It’s easy to see why Monica was so exasperated by his failure to ‘commit’. When he was taken into hospital following a collapse, she rushed from Leicester to his bedside, yet he wouldn’t let her stay in his (empty) flat in case she read his diaries. And when she raised the question of money and inheritance, he claimed to have a phobia about making a will.

He makes hardly any effort to visit her – even though she lived only a few miles from his mother, who he visited regularly. Or he would ‘call in’ for just an hour on his way back from London. Even when he had two sabbatical terms as a fellow at All Souls Oxford, he found all sorts of reasons not to make the make the short journey up to Leicester, including not wishing to drive at night.

There is quite an excruciating series of letters in 1964 and 1965 where he tries to wish away her wounded feelings when she found out about his parallel affair with Maeve Brennan, a colleague in the Library at Hull. He admits his culpability, but doesn’t feel he can do anything about it, and admits he would be ‘shattered’ if she were to do the same from her independent base in Leicester. It’s perhaps as well that Monica never seems to have realised at the time that there was a ‘third woman’ with whom he shared sexual comforts – his matronly secretary Betty Mackereth.

Later in their tortured lives, the tensions between them were eased somewhat by the arrival of ill health. Monica fell downstairs, then afterwards developed shingles. Larkin took her into his house and looked after her, finally acknowledging that they were a ‘couple’. He made her his literary executor, then following his own sudden demise, Monica stayed living in the house until her own death in 2001.

He was an amazingly acute observer and a sound judge of character. One of Monica’s favourite students (and would-be swain) went on to become a lecturer at Manchester University, where he was renowned for his idleness. Larkin pins him down in a single sentence: “e;[he] will will get on up to a point – the point at which has to do some work”e;. This makes his sketch of F.R.Leavis (then at the height of his fame) all the more amusing:

Well, Leavis … what a ghastly little man! … one of the bores of the century, I’d say — and really a typical Oxbridge don, cocky, smart, full of petty cattiness. Oh dear. And what a bore. ‘I live on my nerves’, he told me .. I don’t wonder that Cambridge, or Downing, can’t stand him at any price … I’ve never met a man so full of himself. Stupid little sod, the ideas rattling in him like peas. No, a typical don, one who likes being a don … I’ve not met a sillier man for many a long day … I’m awfully glad to reflect that I don’t possess a single book by him. Not a single book.

These are a very welcome addition to the successful volume Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, and they seem to cry out for a future collection in which Larkin’s letters are placed alongside those written in reply by Monica Jones. But we will have to be very patient: her correspondence is locked in the Bodleian Library for the next twenty years.

© Roy Johnson 2015

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

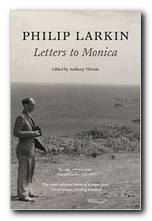

Anthony Thwaite (ed), Letters to Monica, London: Faber and Faber, 2010, pp. 475, ISBN: 0571239102