the philosophy of books, authors, and their readers

Marcel Proust on Reading is a collection of essays and reflections on the relations between writers, text, and readers. When he was only twenty-six Marcel Proust had already written Jean Santeuil, a thousand page would-be novel. It’s a trial run for his much more successful In Search of Lost Time. He realised that it lacked structure and coherence, and in 1897 he abandoned it unfinished. He turned away from fiction and devoted a number of years to studying and translating the works of John Ruskin, who was then at the height of his popularity and influence as an English cultural critic. Proust learned a great deal from him; he imitated his prose style; and he empathised deeply with Ruskin’s belief in the moral value of high art.

Proust’s English was not very good. As he himself admitted ‘I do not claim to know English; I claim to know Ruskin’. And what he also claimed was an ability to read in such a sympathetic manner that he could grasp the underlying personal ‘tune’ of a writer beneath the words on the surface of the page. This skill was something which led him to write a number of Pastiches of famous writers. But it also led him to write the long essay on the philosophy of reading that is at the heart of this collection.

Proust’s English was not very good. As he himself admitted ‘I do not claim to know English; I claim to know Ruskin’. And what he also claimed was an ability to read in such a sympathetic manner that he could grasp the underlying personal ‘tune’ of a writer beneath the words on the surface of the page. This skill was something which led him to write a number of Pastiches of famous writers. But it also led him to write the long essay on the philosophy of reading that is at the heart of this collection.

The essaay is his preface to his translation of Ruskin’s famous collection of lectures Sesame and Lilies. The other items in the book are the original Ruskin lecture On Kings’ Treasuries complete with Proust’s extensive footnotes and commentary, and four short prefaces by Proust to his other translations. The book also has both a foreword and an introduction written by two different translators, commenting on the origin of the texts themselves – quite a curious compilation.

Proust starts out in very typical fashion by talking about the pleasures of reading as a child, but he points out that those stories we love and which we wish could go on forever are not a virtue in themselves so much as a trigger for the memories and associations they allow us to carry into our adult lives.

He explores a whole philosophy of books, authors, and reading, throwing off interesting observations and aphorisms on almost every page:

Indeed, this is one of the great and wondrous characteristics of beautiful books (and one which enables us to understand the simultaneously essential and limited role that reading can play in our spiritual life): that for the author they may be called Conclusions, but for the reader, Provocations.

In other words, the author’s work is complete, but for the reader, this is just the start of an imaginative journey. And of course ‘Reading’ is interpreted in its very broadest sense. One moment he is discussing literature, but then the next it’s paintings, architecture, and philosophy – anywhere the creative spirit can leave its mark.

Ruskin’s lecture purports to be on ‘the treasures hidden in books’, and it does take in the form of empathetic reading that Proust describes. But it is largely a rambling series of lofty over-generalisations offered de haut en bas concerning the evils of contemporary society, which include road tunnels in the Alps, iron foundries in the UK, and ‘new hotels and perfumers’ shops’. Proust’s footnotes offer both a critique of Ruskin’s ideas and an appreciative close reading that demonstrates a practical example of sensing the author’s ‘tune’ beneath the surface of his words.

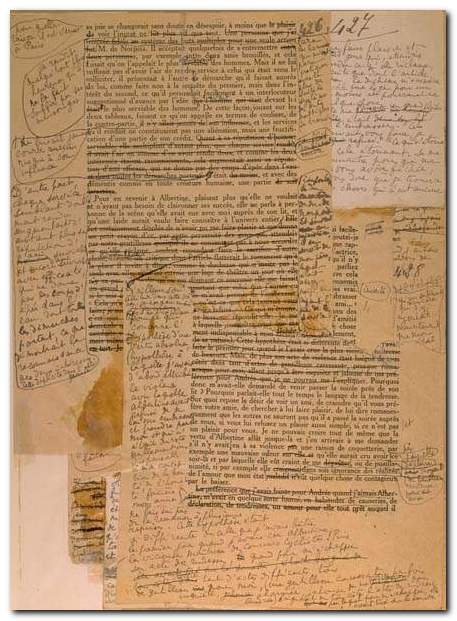

Proust would have loved Hypertext. He is forever inserting examples, asides, correctives, and qualifications into the flow of his text. He is an avid user of footnotes, and of course we know that he composed his works in an accretive manner, with one strip of paper after another glued into the pages of the exercises books he used as he thought of extra things to say.

Proust’s revisions to a typescript

© Roy Johnson 2011

Marcel Proust, On Reading, London: Hesperus Press, 2011, pp.113, ISBN: 1843916169

More on Marcel Proust

Twentieth century literature

More on biography