tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

Falk (1903) is not one of Joseph Conrad’s better-known stories, yet it deserves to be. It is just as successful as Heart of Darkness in exploring powerful and extreme situations. It was first published in the collection Typhoon and Other Tales (1903) and is the only one of Conrad’s stories which did not first appear serialized in magazine publication. This was because the editor objected to the fact that the very powerfully evoked central female character never speaks.

Joseph Conrad

Falk – critical commentary

Inter-textuality

Falk (1903) is composed of many elements Conrad used in his other novels and novellas. The story begins with a group of mariners dining in a small river-hostelry in the Thames estuary discussing seafaring matters – a situation he had already used in Heart of Darkness, which was written the year before. He even uses a similar comparison of the narrative present with a distant past – not that of the Roman invasion, but of primeval man telling tales of his experience.

An unnamed outer-narrator sets the scene, and then the story is taken up by a second and equally unnamed inner-narrator – a type rather like Marlow, the inner-narrator of Heart of Darkness and other Conrad tales. He is recounting events which took place when he was a younger man.

The young man is taking up his first assignment as a captain – a plot device Conrad had used in Heart of Darkness and was to use again in both The Shadow-Line and The Secret Sharer. The location of events is not specified, but it corresponds in many details to Bangkok, which appears in the two later novellas. He is also taking over from a rather dubious previous captain who has died, and his ship is held up in port with a sickly crew.

Characters from other Conrad tales appear in the story: Schomberg the gossipy Alsatian hotel owner who appears in Lord Jim (1900) and Victory (1915); Gambril, the elderly sailor who also appears in The Shadow-Line. And of course Falk’s dreadful experiences drifting powerless on a doomed ship towards the South Pole carries unmistakable echoes of The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner and The Flying Dutchman legend.

A Darwinian reading

It’s possible to argue that Falk is concerned with the elemental forces which man needs in order to survive. In the animal world there are three basic instincts which combine to form a will to prevail – that results in ‘the survival of the fittest’. These are the hunt for food, the urge to procreate, and the fight for territory.

Falk himself embodies all of these forces to a marked degree. He fights to stay alive, and he is even prepared to confront one of society’s most sacred taboos – he will kill and eat human flesh in order to endure and prevail.

His yearning for Hermann’s niece is a powerful, all-consuming physical passion. Despite all his sufferings on board the Borgmester Dahl, his unfulfilled desire for her hurts him more deeply. It is a more painful feeling to endure. ‘This is worse pain. This is more terrible’ he exclaims. It’s interesting to note that when Falk tows away Hermann’s ship by force, the narrator observes ‘I could not believe that a simple towing operation could suggest so plainly the idea of abduction, of rape. Falk was simply running off with the Diana‘.

He gets what he yearns for in the end. And it’s interesting to note that he also asserts his dominance in terms of territory. With his tug boat on the river he has a monopoly over navigation, and can charge whatever he wishes for piloting ships to the open sea. He does a similar thing in the struggle for survival on the stricken Borgmester Dahl by siezing control of the last firearm on board. The young captain reflects ‘He was a born monopolist’.

Falk endures the most extreme conditions imaginable – hunger, deprivation, and the threat of death. As the Borgmester Dahl drifts aimlessly towards the south pole, he inhabits a microcosm of a Hobbesian world. His life is nasty, brutish, and is likely to be short. And he is surrounded by cowards and incompetents. Yet he wills himself to endure; he takes control of the ship; and he is prepared to fight back against man’s inhumanity to man when the carpenter attacks him. He triumphs and survives. ‘They all died … But I would not die … Only the best man would survive. It was a great, terrible, and cruel misfortune.’

The food and eating leitmotif

Imagery of food and eating occur repeatedly throughout the story. The narrative begins with men of the sea ‘dining in a small river-hostelry. And they are compared with their primitive counterparts telling ‘tales of hunger and hunt – and of women perhaps!’amongst gnawed bones.

The young captain dines on chops at Schomberg’s table d’hote and listens (whilst the hotelier eats ‘furiously’) to his complaints against Falk. These complaints are based of food an cooking. Falk refuses to dine at Schomberg’s hotel because he is a vegetarian. He has also stolen Schomberg’s native cook.

Schomberg regards Falk as unnatural because he does not eat meat: ‘A white man should eat like a white man … Ought to eat meat, must eat meat.’ But Falk even bans meat-eating from his own ship, and pays his crew a supplements to their wages for the inconvenience. The young captain reflects ruefully on the state of affairs:

I was engaged just then in eating despondently a piece of stale Dutch cheese, being too much crushed to care what I swallowed myself, let alone bothering my head about Falk’s ideas of gastronomy. I could expect from their study no clue to his conduct in matters of business, which seemed to me totally unrestrained by morality or even by the commonest sort of decency.

This is a wonderful example of the sort of ironic prolepses Conrad embeds in his text. Falk’s ideas of gastronomy have been formed by exactly the same extreme experiences which have influenced his moral attitudes to business and society. He has seen and endured the Worst, and he has survived in the most primitive struggle for existence. And his shock at finding himself forced to eat a fellow human being leads to his choice of vegetarianism. There is therefore a direct link between his gastronomy and his morality. But the young captain does not know that at this point of the narrative.

Falk’s final descent into cannibalism is reinforced by understatement. He tells his bride-to-be and father-in-law: “I have eaten man”.

Story or novella?

There is no clear dividing line between a long story and a novella – in terms of length. At approximately 20,000 words it would be possible to argue that Falk is a long story: The first part deals with a young captain and his experiences on shore in Bangkok: the second part recounts the shocking details of Falk’s experiences on board the Borgmester Dahl.

But the fundamental issues at stake in this story are so profound (the fight for survival – see above) and the concentrated imagery with which the story is articulated is so dense, that this narrative has all the qualities of a novella. It focuses on eating to stay alive, reproducing to continue the human race, and establishing dominance of a territorial space.

It’s true that there are a greater number of named characters in the story than normally appear in a novella – not all of them with important parts to play in the plot. But the focus of attention is largely on Falk, Hermann, and the narrator. Quite astonishingly, Hermann’s niece is also a vital part of the story – even though she is never named, she never speaks, and she does nothing except represent animal magnetism in its most vital form.

Falk – study resources

![]() Falk – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Falk – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Falk – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Falk – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() Falk – Kindle eBook (annotated)

Falk – Kindle eBook (annotated)

![]() Falk – Tredition paperback – Amazon UK

Falk – Tredition paperback – Amazon UK

![]() Falk – Tredition paperback – Amazon US

Falk – Tredition paperback – Amazon US

![]() Falk – eBook at Project Gutenberg

Falk – eBook at Project Gutenberg

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Falk – plot summary

A young mariner (‘not yet thirty’) takes charge of a ship in the far east (Bangkok) when the previous captain dies. The crew are sickly and unfriendly, the ship has no provisions, and there are delays in getting under way. He befriends Hermann, the captain of the Diana, a German ship which is moored nearby. Hermann lives on board with his wife, his four children, and his niece – who is a simple but physically attractive young woman. Hermann is planning to sell his ship and go back to Germany to retire. Also passing time with this family is Falk, the captain of a tug with a monopoly of navigation on the river leading out to the coast.

Falk is a remote, taciturn, and rather forbidding figure who is not popular with the local officials and traders. When the young captain’s and Hermann’s vessels are ready to depart, the young captain is annoyed to discover that Falk takes the Diana out first, damaging Hermann’s ship in the process. The captain tries to hire the one possible alternative navigator, but discovers that Falk has bought him off.

Falk is a remote, taciturn, and rather forbidding figure who is not popular with the local officials and traders. When the young captain’s and Hermann’s vessels are ready to depart, the young captain is annoyed to discover that Falk takes the Diana out first, damaging Hermann’s ship in the process. The captain tries to hire the one possible alternative navigator, but discovers that Falk has bought him off.

It transpires that Falk has taken this precipitate action because he is consumed with a passionate desire for Hermann’s voluptuous niece, and thinks the young captain is a rival. The captain confronts Falk, reassuring him that he has no designs on the girl. Falk asks for his diplomatic assistance in re-establishing good relations with Hermann, so that he can propose to the niece.

The young captain opens negotiations, and Hermann very reluctantly allows Falk to plead his case. But Falk explains that there is one thing the niece should know about him if she is to accept his offer of marriage – the fact that he had once eaten human flesh.

This sends Hermann into a explosion of outraged sensibility. The captain assumes that Falk has been involved in a shipwreck, but Falk explains to him the story of his experiences on a ship which is damaged beyond repair by storms at sea. It drifts helplessly into the Antarctic Ocean, and runs out of provisions. The crew and the captain are feckless, and start to die off or jump overboard. The ship’s carpenter tries to kill Falk, but Falk kills him instead, whereupon he and the remaining crew eat the man before eventually being rescued.

The young captain speaks on Falk’s behalf to Hermann, who eventually consents to the match – motivated partly by saving the cost of an extra cabin (for the niece) on the journey back to Bremen. When the young captain returns to the port five years later, Mr and Mrs Falk are no longer there.

Principal characters

| — | the unnamed outer narrator |

| — | the unnamed inner-narrator |

| Hermann | a German ship master |

| Mrs Hermann | his wife |

| — | his physically attractive niece |

| Lena, Gustav, Carl, Nicholas | the Hermann children |

| Falk | a Danish or Norwegian tugboat captain |

| Schomberg | an Alsatian hotel-keeper |

| Mrs Schomberg | his grinning wife |

| Mr Siegers | principal in shipping office |

| Johnson | former captain, now a drunk who has gone native |

| Gambril | an elderly seaman |

Biography

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

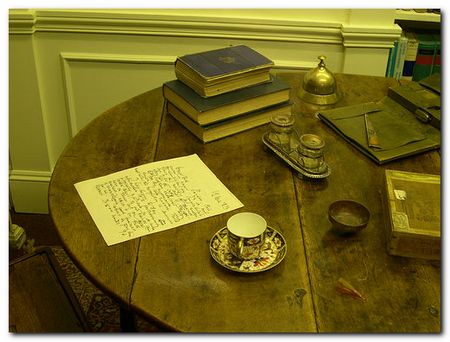

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

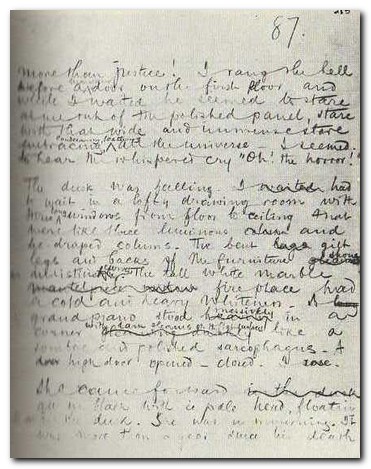

Joseph Conrad’s writing

Manuscript page from Heart of Darkness

Other work by Joseph Conrad

Nostromo (1904) is Conrad’s ‘big’ political novel – into which he packs all of his major subjects and themes. It is set in the imaginary Latin-American country of Costaguana – and features a stolen hoard of silver, desperate acts of courage, characters trembling on the brink of moral panic. The political background encompasses nationalist revolution and the Imperialism of foreign intervention. Silver is the pivot of the whole story – revealing the courage of some and the corruption and destruction of others. Conrad’s narration is as usual complex and oblique. He begins half way through the events of the revolution, and proceeds by way of flashbacks and glimpses into the future.

Nostromo (1904) is Conrad’s ‘big’ political novel – into which he packs all of his major subjects and themes. It is set in the imaginary Latin-American country of Costaguana – and features a stolen hoard of silver, desperate acts of courage, characters trembling on the brink of moral panic. The political background encompasses nationalist revolution and the Imperialism of foreign intervention. Silver is the pivot of the whole story – revealing the courage of some and the corruption and destruction of others. Conrad’s narration is as usual complex and oblique. He begins half way through the events of the revolution, and proceeds by way of flashbacks and glimpses into the future.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Secret Agent (1907) is a short novel and a masterpiece of sustained irony. It is based on the real incident of a bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory in 1888 and features a cast of wonderfully grotesque characters: Verloc the lazy double agent, Inspector Heat of Scotland Yard, and the Professor – an anarchist who wanders through the novel with bombs strapped round his waist and the detonator in his hand. The English government and police are subject to sustained criticism, and the novel bristles with some wonderfully orchestrated effects of dramatic irony – all set in the murky atmosphere of Victorian London. Here Conrad prefigures all the ambiguities which surround two-faced international relations, duplicitous State realpolitik, and terrorist outrage which still beset us more than a hundred years later.

The Secret Agent (1907) is a short novel and a masterpiece of sustained irony. It is based on the real incident of a bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory in 1888 and features a cast of wonderfully grotesque characters: Verloc the lazy double agent, Inspector Heat of Scotland Yard, and the Professor – an anarchist who wanders through the novel with bombs strapped round his waist and the detonator in his hand. The English government and police are subject to sustained criticism, and the novel bristles with some wonderfully orchestrated effects of dramatic irony – all set in the murky atmosphere of Victorian London. Here Conrad prefigures all the ambiguities which surround two-faced international relations, duplicitous State realpolitik, and terrorist outrage which still beset us more than a hundred years later.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2012

Joseph Conrad web links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

![]() Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

![]() Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

![]() Works by Joseph Conrad

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society of America

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

![]() Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales