design, modernism, and constructivism

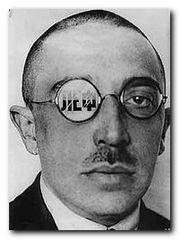

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) was one of the most influential artists to emerge from the explosion of Russian modernism which took place between 1915 and 1923. Initially working as a painter, he stripped bare the canvas and worked with ruler and compasses to devise minimalist pictures which he described as ‘subjectless’. But then given the opportunities presented by the early years of the revolution, he went on to become a designer in furniture and fabrics, ceramics, posters, typography, stage and film design, exhibition display, and radical innovations in photography. He was a central figure in the movement of Russian constructivism, a radical activist, a theorist, teacher, and a pioneer of photo-montage. Alexander Rodchenko Design is an elegantly illustrated introduction to the full range of his work.

After the early abstract designs he moved on to public artworks – kiosks, posters, and theatre designs which you could say provided him with a subject – yet he continued to create what he called ‘spatial compositions’, many of which look like bicycle wheels distorted into three dimensional sculptural arrangements.

After the early abstract designs he moved on to public artworks – kiosks, posters, and theatre designs which you could say provided him with a subject – yet he continued to create what he called ‘spatial compositions’, many of which look like bicycle wheels distorted into three dimensional sculptural arrangements.

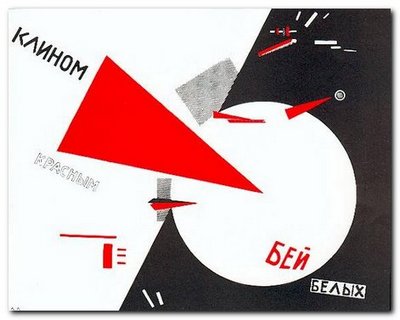

He worked alongside and sometimes in collaboration with Malevich, Kandinsky, and Tatlin, developing his abstract work into three-dimensional paintings, product designs, and constructions that were half way between art works and domestic objects. It was in the spirit of the new communism to produce an art that aimed to be useful, classless, and practical. This was the aim of what came to be called ‘Constructivism’, even if its results were what we would now call modernist art.

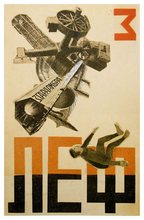

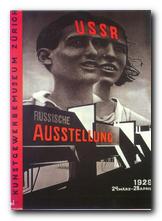

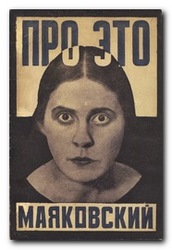

In the early 1920s he produced the work for which he is best known – the combinations of collage images, new typography, and asymmetric graphic design which created the hallmark of Russian modernism. It is this brief period of state-sponsored radical designs that still have an influence today – as you can see in the work of Neville Brody and his many imitators.

His work in the late 1920s and 1930s centred largely on photography, much of it featuring objects shot from unusual angles – street scenes from overhead, trees and chimneys from ground level, all objects highlighted wherever possible by dark expressive shadows.

The illustrations are very well chosen to avoid some of the better-known images. Instead, they draw on quite rare materials from the Rodchenko and Stepanova archive in Moscow, the Burman Collection in New York, and the David King collection in London.

It’s amazing that such an original and gifted artist survived the Stalinist purges (unlike so many others) but then he did produce propaganda work which glorified the regime – including even such projects as the construction of the White Sea Canal in 1933 which cost the lives of 100,000 GULAG prisoners.

In fact the depictions of his subjects become more and more heroic, almost in inverse proportion to the degree of social and political misery in the Soviet Union under Stalin. There is very little evidence (anywhere) of his work beyond 1940, even though he lived until 1956 – although there is one astonishing image in this collection dated 1943-44 which you would swear was a Jackson Pollock painting. But it seems quite obvious that the creative highpoint of his career is the 1920s, when he was free to experiment and theorise with his fellow pioneers, and even (dare one say it) when the state encouraged and supported such experimentation.

In fact the depictions of his subjects become more and more heroic, almost in inverse proportion to the degree of social and political misery in the Soviet Union under Stalin. There is very little evidence (anywhere) of his work beyond 1940, even though he lived until 1956 – although there is one astonishing image in this collection dated 1943-44 which you would swear was a Jackson Pollock painting. But it seems quite obvious that the creative highpoint of his career is the 1920s, when he was free to experiment and theorise with his fellow pioneers, and even (dare one say it) when the state encouraged and supported such experimentation.

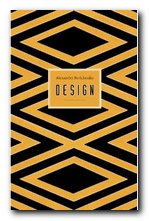

The series of design monographs of which this volume is part feature very high design and production values. They are slim but beautifully stylish productions, each with an introductory essay, and all the illustrative material is fully referenced. Even the cover design is taken from Rochenko’s work. It’s from a 1923 poster advertising Zebra biscuits.

© Roy Johnson 2010

John Milner, Rodchenko: Design, Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club, 2009, pp.98, ISBN: 1851495916

More on art

More on media

More on design

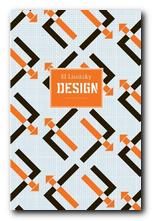

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice. Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.