reading skills for appreciating fiction

If you love reading novels you’ll know that they can offer an entire world in which to get imaginatively lost. People read Wuthering Heights and actually cry when the heroine Cathy dies half way through the story. They read The Wind in the Willows and are utterly charmed by the antics of characters pottering about on a river – all of whom are little animals. Or they read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and are terrified by the story of a scientist who manufactures life and finds the thing he creates going out of control. The important question is how to read a novel in order to get the most out of it?

If you love reading novels you’ll know that they can offer an entire world in which to get imaginatively lost. People read Wuthering Heights and actually cry when the heroine Cathy dies half way through the story. They read The Wind in the Willows and are utterly charmed by the antics of characters pottering about on a river – all of whom are little animals. Or they read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and are terrified by the story of a scientist who manufactures life and finds the thing he creates going out of control. The important question is how to read a novel in order to get the most out of it?

It’s true that some people read novels ‘just for the story’, or ‘to see what happens next’. Once they have finished reading, they retain only a vague notion of what the novel was about, and they pass the book on to the local charity shop. But to understand novels at a deeper level and to get more from them, all you need to do is keep a few issues in mind whilst you’re reading. It’s not difficult – and with practice, it becomes easier, then second nature.

What you will be doing is keeping one part of your attention focussed on the events of the story, but other parts on how the story is being told, features of the characters, and the finer points of language in the text. You will become an intellectual multi-tasker.

These guidance notes will give you some idea of things to look for, and activities you might not have thought of before. This approach will help you find greater depths and meanings in the world of fiction. It will also help you to understand how skilled authors put a story together, and how their works are full of subtle and complex effects which make their fictional worlds believable to us.

1. The author

Make a note of the author’s name – and try to find out something of the background or biography. If the author is well known, simply type <Author Name Biography> into Google, and you will get the life story plus links to further reading at Wikipedia.

What are the author’s dates? The answer to this question gives you a historical context into which the book and its author can be placed. More on this later.

There is no guaranteed one-to-one connection between authors’ lives and the stories that they write, but most novelists write about issues that interest them or have touched their imagination in some way.

Has the author written any other books of the same kind? Where does the one you are reading appear in the list? Does it fit into a particular genre – which means the type of story. Is it a romance, thriller, or detective story? Each of these genres has its own ‘rules’.

For instance best-selling Agatha Christie specialised in detective stories. We admire the way her sleuths Hercule Poirot and Miss Marples solve crimes from shrewdly observed details. But we wouldn’t expect them to behave in the same way as secret agent James bond in Ian Flemming’s spy thrillers.

2. The book

Pick up the book you’re going to read. What do you know about it already? There’s a lot of information about it that’s part of the book itself. The back cover might give you a taster of the plot or details of the author.

When was the book first published? Turn inside to the title, then look on the next page, which usually gives details of its publication. Has it been reprinted a number of times? That’s usually a sign of its popularity.

First published 1988

Reprinted 1990, 1992, 1994

Second edition 1996

New introduction (c) Simon Blackstaff 2005

This tells us that the book was successful on first publication, that a new edition was created after less than ten years, and that after seventeen it has been dignified with an introduction.

Have a look at the opening of the novel. Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities begins

It was the best of times: it was the worst of times.

You just know that this is going to be a novel of tension and conflict from the very opening sentence.

3. The introduction

The book might have an introduction – often written by someone other than the author (as in the example above). This will usually give you information about the characters and themes of the novel – which could be helpful in telling you what to look out for.

It should not give away crucial details of the plot. But no matter how carefully written, it’s bound to influence the way you read the novel. You have two choices. You can read it either before or after you read the novel.

As you develop more experience and confidence, you’ll probably choose to read the introduction after reading the novel. This will enable you to form your own opinions of the book, without being influenced from the outset.

4. The story

In a novel, the story is basically a sequence of what happens in the book. It is a narrative of events arranged in some time sequence. As a reader, you are being invited to follow this sequence until you reach the end of the novel and have the complete picture in your mind.

Most people have no trouble in understanding a simple series of events – even if they contain flashbacks or a jumbled time-sequence. That’s because almost everybody has followed stories in books, newspapers, and on television. Problems only arise when the novel is long, complex, and contains lots of characters.

When that’s the case, you will need to become a more active reader. This means making a brief note of what happens in each chapter – plus creating a list of characters.

These notes and lists will help you in two ways. You will have a record of names and events to which you can refer. But more importantly, the very act of writing them down will help you to remember them.

5. The characters

Authors can choose any number of ways to make their characters realistic, memorable, or convincing. They might give them a striking physical appearance, make them act in a vivid manner, or have them speak in a way that stands out.

Miss Havisham, the embittered old woman in Great Expectations, was jilted at the altar, and has been wearing her wedding dress ever since. The detective Sherlock Holmes plays the violin (and takes opium!) whilst he is solving crimes. Humbert Humbert in Lolita makes literary jokes whilst he is murdering his rival, Clare Quilty. Heathcliffe in Wuthering Heights jumps into the grave of his true love Catherine Earnshawe, wishing to embrace her as if she was alive. You will not forget these characters after reading about them.

At the opening of Pride and Prejudice it might not be easy to distinguish between Mr Bingley and Mr Darcy when they set the hearts of the Bennet girls fluttering. But if you make brief notes on what you know about them (age, home, appearance) it will help you to understand their roles in the story.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

5. The plot

In a novel, the story is basically the sequence of what happens. It’s not the same thing as the plot. E.M.Forster explained the difference as follows:

“The king died and then the queen died” is a story. “The king died, and then the queen died of grief” is a plot.

The key difference here is that element of causality. There is some significant reason connecting events in the story. In a murder story the detective eventually finds hidden connections between clues to solve a crime. In Pride and Prejudice the heroine Elizabeth Bennett overcomes her prejudice and realises that the hero Mr Darcy is in love with her after all. In Great Expectations the hero Pip eventually realises that his true benefactor is not a rich woman but a convict he helped to escape as a child.

Some novels have plots that are quite difficult to unravel, but good authors normally give readers enough evidence to be able to work out what is going on. Hidden solutions and surprise endings produced like rabbits out of a hat leave readers feeling cheated.

6. The theme

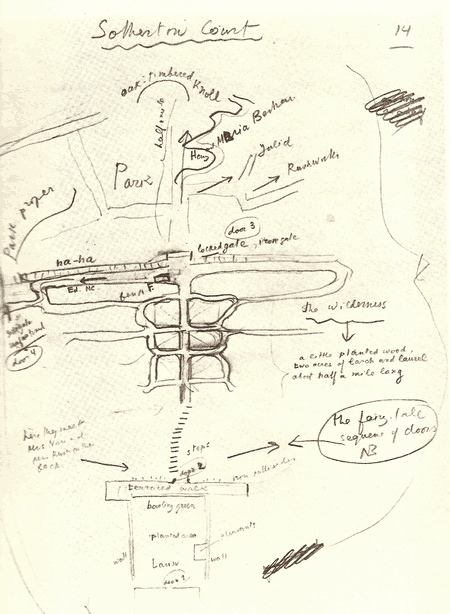

The theme in a novel is not the same thing as the story or plot. It’s something larger and more general – like a single concept, or the moral of the story. For instance Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park explores the theme of education. It’s a story of a young girl who goes to live with rich relatives and eventually marries their youngest son. But almost every character in the novel learns a lesson from mistakes or errors of judgement they make.

So – the story is a version of the Cinderella tale – the poor young girl who eventually gets her prince. But the theme of the novel is a more subtle issue, running through the lives of other characters as well.

7. The style

The style in which a novel is written will reveal one very important factor – the author’s attitude to the content of the story. This will give you some idea of how to ‘read’ the novel: that is, how to understand and appreciate it.

Here’s the opening of Raymond Chandler’s 1939 hard-boiled detective novel The Big Sleep.

It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

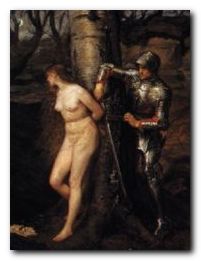

The main hallway of the Sternwood place was two stories high. Over the entrance doors, which would have let in a troop of Indian elephants, there was a broad stained-glass panel showing a knight in dark armor rescuing a lady who was tied to a tree and didn’t have any clothes on but some very long and convenient hair. The knight had pushed the vizor of his helmet back to be sociable, and he was fiddling with the knots on the ropes that tied the lady to the tree and not getting anywhere. I stood there and thought that if I lived in the house, I would sooner or later have to climb up there and help him. He didn’t seem to be really trying.

This is a first-person narrative. The fictional detective Marlowe is relating the story – so his manner of expression tells us a lot about him. It also tells us how the author Raymond Chandler is inviting us to view the story.

The literary style provides us with lots of conventional details – his suit, shirt, and shoes – but then he reveals that he is ‘sober’. This not only tells us that he normally drinks a lot, but his comment ‘I didn’t care who knew it’ is the sort of amusing and ironic inversion that helps to create his witty yet tough-guy persona.

‘I was calling on four million dollars’ In a factual sense he is visiting someone rich: but the expression does a lot more. This is a compressed figure of speech (metonymy) which also characterises the crime novel. It’s like a cartoon, with everything summed up in a single vivid image.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

8. The setting

It is possible to have novels with no setting. The events might take place in a character’s mind – as in Dostoyevski’s Notes from Underground for instance, or Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable. But most novelists will try to convince readers to take their stories seriously by giving them a credible setting. Charles Dickens’s Bleak House is set in a London whose streets we can still walk down; and the events of Tom Woolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities can be traced on a street map of New York – as we once did when I was teaching that novel.

Some novelists are able to evoke the spirit of a place so vividly that literary tourists are attracted from all over the world to visit the locations. Bath is full of Jane Austen fans, re-tracing the steps of characters from Nothanger Abbey, and large parts of south-west England (Dorset, Wiltshire, and Somerset) attract visitors to Thomas Hardy’s fictional region of Wessex. He might have changed the name of the hills above Dorchester to Egdon Heath, but his passionate description of the countryside is so vivid and powerful that readers will travel half way round the world to see the original.

9. Historical context

This term means ‘social conditions at the time the novel was written’. In other words, the sort of things that were happening, how people behaved, and what they believed in the period the novel was written. Your awareness of these matters will depend upon the depth of your historical knowledge, and it is something which you will develop, the more your read.

Why is it important? Here’s an example – from Jane Austen again. Any number of her young female characters have their eye fixed upon marriage, but they have to be very careful about choosing the right man. All sorts of moral problems arise in her novels about making the right decision. If something goes wrong and the engagement goes on too long or is broken off, it will be regarded as disastrous.

You might think – what’s the problem? She can simply choose somebody else.

But in polite society during the early nineteenth century, women were not free to act as they wished, and certainly not free to choose a husband. A broken engagement would cast a dark shadow over a young woman’s reputation. It would be thought that if her fiance broke off the engagement, there must be something wrong with her.

The same suspicion would even fall on an engagement that was protracted. If the man had made his choice (it was the man who proposed) then his failure to follow through would immediately arouse suspicion – on the woman.

The stories and plots of any number of novels rest on social conditions quite unlike our own, and in fact at a more advanced level of reading the content of novels is one of the richest sources of social history we may have about a period.

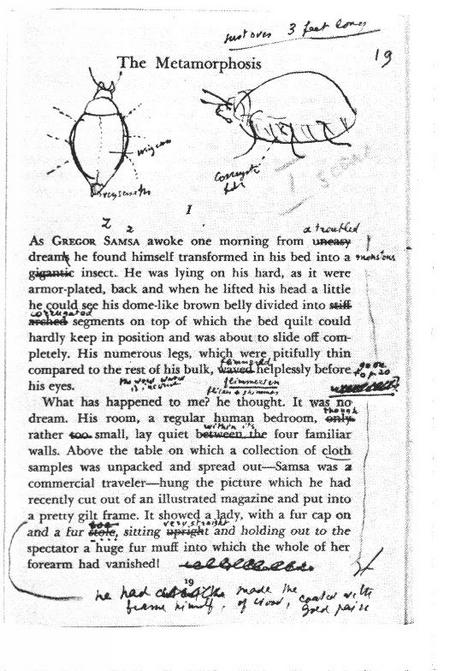

10. Reading and taking notes

Novels will yield up more of their riches if you are prepared to do a little work whilst reading them. This means making notes as you go along. You can make a note of anything that strikes you as interesting, but here are some suggestions:

- the appearance of characters

- recurring themes or motifs

- features of the author’s style

- plot twists or crucial scenes

- important details of the story

It’s certainly a good idea to summarize the events of each separate chapter. This will help you keep the events of the story in your mind.

Some do’s and don’ts

If something strikes you as important or interesting, underline the text – but also put a word or two in the margin that gives it a title. In other words, give a name to what you think is important.

Don’t underline whole paragraphs: that creates an ugly page, and it’s a waste of time. Instead, write a note in the top or bottom margin, saying what you think is important. Or put a circle round a name or a special couple of words.

Teaching the Novel and Reading for Pleasure

Salman Rushdie

© Roy Johnson 2011

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

1. In preparation for writing a piece of work, you should take notes from a number of different sources: course materials, set texts, secondary reading, interviews, or tutorials and lectures. You might gather information from radio or television broadcasts, or from experiments and research projects. The notes could also include your own ideas, generated as part of the planning process.

1. In preparation for writing a piece of work, you should take notes from a number of different sources: course materials, set texts, secondary reading, interviews, or tutorials and lectures. You might gather information from radio or television broadcasts, or from experiments and research projects. The notes could also include your own ideas, generated as part of the planning process.