a novel in fragments

The Original of Laura (Dying is Fun) is a novel from beyond the grave by Vladimir Nabokov. Everyone has now woken up to the fact that Nabokov has been writing stories and novels about older men and younger women (and even younger girls) for quite some time. It’s no good taking his word for it (as he claims in his preface) that the original inspiration for Lolita came from a ‘painting’ by a chimpanzee in the Jardin des plantes. He had already written an entire novella (The Enchanter 1939) on exactly the same theme of what is now technically classed as paedophilia.

We now have his posthumous (and presumably last) work, which has been released even though he made an express wish that it should not be published if it were to be unfinished at the time of his death. And it certainly isn’t finished. Even to call it ‘a novel in fragments’ is stretching definitions somewhat. It consists of the drafts of three discernable and coherent chapters, plus lots of notes for other vaguely related materials which Nabokov was working on at the time of his death in 1977.

We now have his posthumous (and presumably last) work, which has been released even though he made an express wish that it should not be published if it were to be unfinished at the time of his death. And it certainly isn’t finished. Even to call it ‘a novel in fragments’ is stretching definitions somewhat. It consists of the drafts of three discernable and coherent chapters, plus lots of notes for other vaguely related materials which Nabokov was working on at the time of his death in 1977.

The novel-to-be seems to contain two main themes. The first is the sexual life of a flirty young girl called Flora (aged twelve in the semi-completed chapters) who is pursued lecherously by an ageing roué called (believe it or not) Hubert H. Hubert. She survives this and moves with her mother to an American college, where she studies French and Russian. Readers of Nabokov’s other novels will recognise elements from Laughter in the Dark, Lolita, and Pnin already.

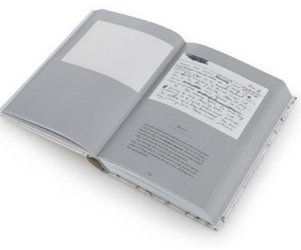

Part way through, the index cards on which Nabokov famously composed his novels change from relating a story to notes and instructions to himself – ideas for the plot, memos to invent a plausible name for a pharmaceutical, and lists of unusual words he was obviously striving to coin.

The second theme, which gives the book its sub-title, concerns Dr Philip Wild, a teacher at the college, whom Flora eventually marries. He is overweight, has bad feet, and he embarks on a quest of what he calls ‘dying by auto-dissolution’. It seems quite clear that the connections between these two parts of the narrative had not been conceptualised by Nabokov – which provides an interesting glimpse into his methods as a writer.

There are also hints that his story is the original source material for another book called My Laura written by somebody else that went on to become a best-seller. Here we have further echoes of Lolita, and typical Nabokovian playfulness – but since this theme remains undeveloped it warrants little attention.

This brings us to the book as a physical object and a product of print production. It’s the nearest a reader could get to seeing the system of writing for which Nabokov was famous. The index cards on which he wrote are photographically reproduced at the top of each right-hand page, with the text of the card reproduced below, complete with mis-spellings, grammatical errors, and slips of the pen.

The cover of the book is a photo-print of a typical index card, and each of the 138 index cards also has perforated edges, so theoretically they can be removed from the book and arranged in a different order if required. I imagine this gimmick will be dropped when the book is published in paperback, but Nabokovians and bibliophiles will undoubtedly want to possess this novelty edition.

That’s the good part. The not-so-good news is that the book is set in a font (Filosofia, by Zuzana Licko) which is a version of Bodoni. The body text is quite elegant and readable, but some headlines are set in the font’s unicase version, which has capitals and lower case of the same height. I am quite confident that Nabokov would have detested such affectation, and the results on some pages look awful.

The book has been created by Chip Kidd, a respected graphic designer, but I’m afraid this does not add anything to the appeal of this particular book or to Nabokov’s oeuvre as a whole. The index cards come out of this well enough, but reading the text in black print on dark grey paper is no joke.

The story is presented in an interesting and very allusive manner. There are unexplained shifts in the temporal sequence of events and the narrative point of view. These suggest that Nabokov was still experimenting with narrative strategies right up to the end of his life. [I have examined this phenomenon in my study of his short stories.] However, it has to be said that in common with the prose style of his other late works, it is contaminated by lots of irritating quirks and tics, such as his weakness for alliteration – though it might be slightly unfair to judge him from what was obviously a work in progress.

‘foetally folded … narrow nates … He brought from the favourite florist of fashionable girls a banal bevy of bird of paradise flowers’

It has been claimed that Nabokov would envisage a novel complete in his mind before starting to write it. This was supposed to allow him to work on any section his wished, then place a card in the stack already written. The cards in this volume cast severe doubts on that claim. There is some sense of fluency in the semi-completed chapters, but it’s of a kind that characterises his less distinguished novels; and the remainder prove that he was thinking aloud and making it up as he went along.

The volume has a preface written by his son Dmitri which is a pompous and badly-written piece of self-indulgence that tells us very little about the manuscript and why it came to be published. What it does tell us is how not to behave as the offspring of a famous person.

So, it’s a production with a number of interesting features. It’s clearly a piece of gross commercial opportunism; it gives more ammunition to those who see Nabokov as a great writer with a dubious interest in under-age girls; it’s unlikely to enhance his reputation as a writer; but for me it’s a fascinating glimpse into the writer’s workshop – and further proof that we shouldn’t take what writers say about their own motivations and methods at face value.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Vladimir Nabokov, The Original of Laura: (Dying is Fun) a novel in fragments, London: Penguin, 2009, pp. 278, ISBN 0141191155

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories