tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

Ultima Thule was written in 1939/40 as the first chapter of a novel which was never finished – the second chapter being Solus Rex. It was one of the last pieces Vladimir Nabokov wrote in Russian before switching to write in English, which he continued to do for the next twenty years during his stay in America. It was first published in the emigré journal Novyy Zhornal in New York in 1942, and then appeared in English translation (by Dmitri and Vladimir Nabokov) in the New Yorker in 1973. It was then collected in the volume of stories A Russian Beauty and Other Stories published later the same year.

It is difficult to escape the suspicion that Nabokov embellished the story whilst engaged in the process of translation for the 1973 publication. The style of the piece has many of the features of his late, Rococo mannerism – the persistent use of alliteration, a straining for obscure vocabulary, and a wilful, almost irritating wordplay. There is certainly a case to be made for a scholarly comparison of the original 1942 Russian text with its revised counterpart of thirty years later.

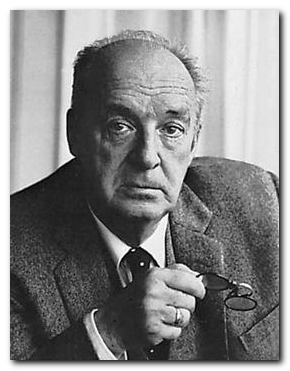

Vladimir Nabokov

Ultima Thule – critical commentary

Nabokov published a number of ‘stories’ which were in fact chapters from longer works – such as his novels or his memoir Speak, Memory. This was common publishing practice at the time, and Nabokov was living a financially precarious life as an exile in an almost hand-to-mouth manner.

Ultima Thule is primarily a character study – and a protracted philosophic argument somewhat reminiscent of The Magic Mountain (a comparison which Nabokov would intensely dislike). It also contains fictional elements which are not developed – such as Sineusov’s relationship with his wife, a complex time sequence, and the ambiguous nature of Falter himself, who could be a charlatan or a gifted visionary.

These elements might have been taken up in later parts of the projected novel, and Nabokov comments on them in the introductory notes to A Russian Beauty and Other Stories in which the story appeared:

Perhaps, had I finished my book, readers would not have been left wondering about a few things: was Falter a quack? Was he a true seer? Was he a medium whom the narrator’s dead wife might have been using to come through with the blurry outline of a phrase which her husband did or did not recognise?

These authorial observations are doubly significant. First, from the point of view of the story itself, they reinforce the idea that Falter is a deliberately ambiguous figure. Sineusov describes his former tutor as if he were some sort of preternatural genius – but Falter is a shabby, down at heel character who works in the wine trade and stays in seedy hotels. Following his ‘vision’ he claims to have some transcendental insight into the human condition, but chops logic with Sineusov and gives specious arguments for not revealing the nature of this Universal Truth.

But the remarks also reveal something interesting about Nabokov’s methods and practice as a writer. He is at great pains to claim elsewhere that he composed all his works completely, in his head, then on his famous index cards, before he started writing them.

Following the posthumous publication of The Original of Laura, we now know that this claim is not to be taken at face value. The index cards which were published along with that last unfinished novel reveal that he was making up the story as he went along. And these retrospective observations on Ultima Thule demonstrate the same thing. If Nabokov did not know the answers to those questions his readers might ask, then the story was not complete in his mind when he came to write it.

Ultima Thule – study resources

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov – Amazon UK

![]() Zembla – the official Vladimir Nabokov web site

Zembla – the official Vladimir Nabokov web site

![]() The Paris Review – 1967 interview, with jokes and put-downs

The Paris Review – 1967 interview, with jokes and put-downs

![]() First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection of photographs

First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection of photographs

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

![]() Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

![]() Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

![]() Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

![]() Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

![]() Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

![]() Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

![]() David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

![]() Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Ultima Thule – plot summary

The narrator, an artist Gospodin Sineusov is grief-stricken following the death of his wife. He addresses her as if she were alive and recounts their meeting with his former tutor Adam Falter.

Sineusov thinks that Falter is gifted with ‘volitional substance’ and claims that he is an exceptional individual. But some time later Sineusov hears that Falter has had a violent seizure in a hotel on the Riviera, then gone slightly mad. Falter is treated by an Italian psychologist Dr Bonomini, who questions him about the seizure. Falter claims that he revealed to Bonomini the solution to ‘the riddle of the universe’ – but the shock of this revelation killed him (though actually, it was a heart attack).

Whilst his wife is in hospital, Sineusov is commissioned to produce illustrations for a Nordic epic called Ultima Thule. When the epic’s author disappears and his wife dies, Sineusov nevertheless continues to work on the series of drawings as a distraction from his grief. He decides to return to Paris.

Before leaving he asks Falter to reveal what he told the Italian doctor. Falter refuses, and instead they have a cat and mouse philosophic debate about ‘essences’ and ‘being’. Falter insists that he has had a gigantic Truth revealed to him, and Sineusov enters into a guessing game, but Falter eludes all attempts to extract the secret from him.

Sineusov poses questions such as ‘Does God exist?’ and ‘Is there an afterlife?’ But Falter argues that the questions are falsely predicated and evades answering them. He then reflects on human beings and their fear of death – and finally leaves.

Sineusov later receives a bill for 100 francs for the consultation, and is left feeling that he must remain alive so as to preserve the memory of his dead wife.

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon UK

Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon US

Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon US

Other work by Vladimir Nabokov

Pale Fire is a very clever artistic joke. It’s a book in two parts – the first a long poem (quite readable) written by an American poet who we are encouraged to think of as someone like Robert Frost. The second half is a series of footnoted commentaries on the text written by his neighbour, friend, and editor. But as we read on the explanation begins to take over the poem itself, we begin to doubt the reliability – and ultimately the sanity – of the editor, and we end up suspended in a nether-world, half way between life and illusion. It’s a brilliantly funny parody of the scholarly ‘method’ – written around the same time that Nabokov was himself writing an extensive commentary to his translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

Pale Fire is a very clever artistic joke. It’s a book in two parts – the first a long poem (quite readable) written by an American poet who we are encouraged to think of as someone like Robert Frost. The second half is a series of footnoted commentaries on the text written by his neighbour, friend, and editor. But as we read on the explanation begins to take over the poem itself, we begin to doubt the reliability – and ultimately the sanity – of the editor, and we end up suspended in a nether-world, half way between life and illusion. It’s a brilliantly funny parody of the scholarly ‘method’ – written around the same time that Nabokov was himself writing an extensive commentary to his translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories