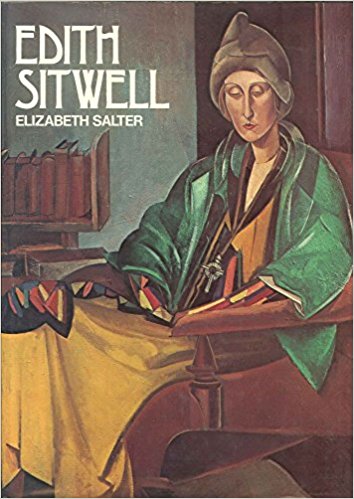

modernist poet and English eccentric

Edith Sitwell (1887-1964) was an English poet, and an upper-class eccentric renowned for her exotic clothing and over-sized jewellery. She was prolific as a writer, and in the 1920s and 1930s was classed as an avant-garde modernist. Her work was praised by critics and fellow poets, but she is now known almost exclusively for her poems Parade which were set for music-theatre performance by the composer William Walton.

She was born into an aristocratic family at Renishaw Hall in Derbyshire, the eldest of three children who remained close throughout their adult lives. She disliked both her parents, never married, and spent much of her life living with her childhood governess.

Her remote and snobbish parents would only issue instructions to a butler and private servant. Other staff in the household were not permitted to speak to the masters. She developed a youthful love for Chopin, Brahms, and Swinburne- and when asked what she wanted to be when she grew up answered “A genius”.

Her father disapproved of education for women, so Edith was largely self-taught. However, her governess Helen Rootham was a powerful influence and provided an introduction to the world of modern art – Rimbaud in particular.

When Edith was twenty her famously beautiful mother was put on trial for fraud, and having been convicted, served a short jail sentence. The family never spoke about this incident – even to each other.

In 1913 at the age of twenty-five Edith was given her freedom and moved to live at Pembridge Mansions in Bayswater, London. By upper-class standards, this was quite a Bohemian location. It was at this point that she began writing poetry. The rooms at Pembroke Mansions became a cultural salon that attracted figures such as Aldous Huxley, Virginia Woolf, and Cecil Beaton.

Like many other artists and intellectuals of the modernist period she was opposed to the First World War. In 1916 she established a magazine Wheels that published the work of young unknown poets, including in its 1919 edition six pieces by Wilfred Owen, who had been killed in action the year before.

She fell in love with a handsome young Chilean painter called Alvaro Guevara. He however was infatuated with the heiress and left-wing activist Nancy Cunard. Edith consoled herself with the fame which followed her early success. It is assumed by her biographers that she remained a virgin for the rest of her life.

In 1923 her poems Facade were set to music by the young William Walton who Sitwell and her brothers had decided to champion. The result was a surrealist entertainment in which the poems were declaimed through a megaphone from behind a decorated curtain, accompanied by jagged and heavily syncopated music. It caused public outrage at the time, yet ironically it is the work by which she is now best known.

Her controversial social success, eccentric costume, and poetic experiments also generated a great deal of rivalry and animosity. Noel Coward lampooned Edith and her brothers as The Swiss Family Whittlebot, and F.R. Leavis observed that the Sitwells ‘belonged to the history of publicity’ – which in retrospect seems largely true.

She went to live in Paris with Helen Rootham, where she was introduced by Gertrude Stein to the second great love of her life – the Russian painter Pavel Tchelitchew. She devoted herself to him, became his muse and patroness, and travelled extensively with him, all the time seemingly unaware that he was a homosexual.

In 1930 Helen Rootham was diagnosed with cancer, which suddenly transposed Edith into the role of carer. She was living on a modest allowance from her father, and supplemented this by turning to journalism. She wrote articles for the newspapers in which she articulated her controversial views on issues of the day.

But on Helen Rootham’s death she also suffered another blow – Pavel Tchelitchew decided to emigrate to America. This was an emotional low point for Edith, and she was persuaded to return to the family’s ancestral home by her brother Osbert. (Her father had gone to live in a castle in Tuscany he spent thirty years restoring.)

This move brought on a fresh lease of poetic life and further critical acclamation from the likes of Kenneth Clark and Cyril Connolly, who predicted that her work would outlive that of T. S. Eliot and W.H. Auden (in which he has so far been proven wrong). There was also an invitation to make a celebrity lecture tour in the United States. Further public accolades were heaped upon her, and even though she was regarded as something of a professional eccentric, she was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1954.

But fame did not bring her happiness. She became financially dependent on her brother, and she felt herself the poor relation. She imagined herself to be a ‘working woman’ but in fact ran up enormous debts in the family name.

Osbert was able to offer her summer residence in the Derbyshire stately home and winters in the Tuscan castle he inherited from his father – so she was not exactly slumming it. There was also the ‘season’ in London, when she lived at the Sesame Club in Mayfair, driven around in a chauffeur-driven Daimler of gigantic proportions. In her later years she became infirm and was confined to a wheelchair. She died in 1964, suffering from alcoholism and paranoia.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Facade – Buy the book at Amazon UK

Facade – Buy the book at Amazon US

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on literary studies

More on the arts