the romance, the double, the psyche

Although Frankenstein is constructed from many of the basic elements of the romantic novel, Mary Shelly seems to have raised her ‘ghost story’ (1) well above the level of mere occasional entertainment for which it was intended. Her importation of mythical strains and psychological insights which, however inchoate or unconsciously expressed, leave the novel still speaking meaningfully and tantalisingly to us today, long after serious interest in most supernatural horrors and Italianate castle-wanderings has faded.

The notion that her achievement is somewhat ‘accidental’ is suggested by the fact that the standard elements of romanticism are used in such a haphazard fashion. Some of them contribute to the strengths of the story, whilst others create its major weakness. But what elevates the novel, quite apart from its sheer narrative vigour, is the expression she gives to features of the conscious and the unconscious mind which lie deep beneath the surface of the story.

The notion that her achievement is somewhat ‘accidental’ is suggested by the fact that the standard elements of romanticism are used in such a haphazard fashion. Some of them contribute to the strengths of the story, whilst others create its major weakness. But what elevates the novel, quite apart from its sheer narrative vigour, is the expression she gives to features of the conscious and the unconscious mind which lie deep beneath the surface of the story.

The most obvious of the standard elements of romanticism are The Romantic Hero, Nature, Sentiment, The Macabre, and Death. Frankenstein doesn’t have just one romantic hero – it has three. And yet this triplication is well enough controlled to constitute a strength in the narrative rather than a double redundancy. First there is the outer narrator – Walton, a self-educated and ambitious man, a disappointed poet who has inured himself to great hardship in order to undertake a dangerous journey of exploration. He feels solitary, lonely, and yearns for a friend, declaring to Frankenstein his ‘thirst for a more intimate sympathy with a fellow mind’. His declaration falls on fertile ground, since Frankenstein has had a close friend (Clerval) but lost him – one of the many ironic parallels and reversals in the novel.

Frankenstein himself is of course the central romantic hero – another intelligent and well-educated man who, out of noble if dangerous ambition to act in a God-like manner – creating life – brings misery, isolation, and eventually death upon himself and others.

We tend to forget Walton for most of the narrative, but the third hero is present from his ‘birth’ onwards in almost symbiotic relation to his creator. And the Monster is quite pointedly similar to the other two. He is sensitive and well-educated, and initially well disposed towards his fellow men. But he too feels a painful yearning for a ‘friend’ – in his case a mate – and because Frankenstein has both made him repulsive to other humans and refused to create a female companion for him, the Monster feels doubly excluded: ‘I am solitary and abhorred’. His acts of revenge set him eternally apart from society, and although we know that he still entertains high aspirations and delicate sentiments, his tragedy is to be doomed and self-destructive – just like his creator.

These three figures share in varying degrees one of the standard requisites of the romantic hero – an unfulfilled or incomplete relationship with the opposite sex. Walton is a twenty-eight year old bachelor whose only contact with women is that via correspondence with his ‘beloved sister’ – the chaste version of this phenomenon.

Frankenstein on the surface seems to be more healthy. He has an enthusiastic regard for Elizabeth, his ‘more than sister’ – the blue-eyed, high-born orphan who in the earlier version of the story was his cousin (2). But it is significant that Frankenstein puts a long delay on his marriage to Elizabeth, he never consummates it, and as Robert Kiely rather wittily points out, if Frankenstein labours for two years trying to create life ‘we may wonder why he does not marry Elizabeth and, with her co-operation, finish the job more quickly and pleasurably’ (3)

The monster is the more pitiable case. He longs quite explicitly for a mate with whom he can reproduce his own kind, but he too comes no closer to a sexual connection with Woman than the typically romantic union-through-death when he murders Elizabeth.

Another common feature of the romantic hero is shared by Walton, Frankenstein, and the Monster. All of them are powerful egoists who claim that their sensitivity and suffering is greater than that of others. Walton claims that he is different from ordinary mortals because of his solitary self-education, but he puts it in typically self-aggrandising form: ‘I have thought more, and … my day dreams are more extended and magnificent’.

Another common feature of the romantic hero is shared by Walton, Frankenstein, and the Monster. All of them are powerful egoists who claim that their sensitivity and suffering is greater than that of others. Walton claims that he is different from ordinary mortals because of his solitary self-education, but he puts it in typically self-aggrandising form: ‘I have thought more, and … my day dreams are more extended and magnificent’.

Frankenstein takes this sort of claim merely as a starting point for himself. As soon as his troubles get under way he frequently claims to be the most accursed and tormented of all mortals. When Justine is about to be hung (for a crime for which he is indirectly responsible) he suggests that his pain is greater than hers:

The tortures of the accused did not equal mine; she was sustained by innocence, but the fangs of remorse tore my bosom, and would not forgo their hold.

Egomania reaches a high point in Frankenstein, but it is outstripped by the Monster in the soliloquy on his creator’s death: ‘He suffered not … the ten thousandth portion of the anguish that was mine’ and ‘Blasted as thou wert, my agony was still superior to thine’.

It is the interplay, the correspondences, and the conflicts between these three typically romantic heroes which gives the novel so much of its richness. The romantic mise en scène on the other hand tends to be rather commonplace except where Mary Shelley has the confidence to exaggerate it as a form of dramatic heightening. The Rousseauesque location of Geneva in which Frankenstein is raised seems nothing more than a conventional background, and the rural idyll of de Lacey’s cottage and its surroundings where the Monster is educated is somewhat schematic, a setting dictated by the notion of ‘natural man’ being expounded at that point in the story.

Notes

1. Mary Shelley’s own introduction to the novel. Oxford University Press edition (2011) which reprints the 1831 text. All subsequent quotations are from this edition.

2. James Rieger (ed), Frankenstein, New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1974, which reprints the 1818 text.

3. Robert Kiely, The Romantic Novel in England, Harvard University Press, 1972.

4. Kiely gives an account of this reading, combining it with the Frankenstein/Shelly as Prometheus reading.

Christopher Small, Ariel Like a Harpy, London: Gollancz, 1972, which also covers exhaustively the biographical readings of the novel.

6. Masao Miyoshi, The Divided Self, New York: New York University Press, 1969.

7. Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id, London: Hogarth Press, 1962. All subsequent quotations are from this edition.

8. Cited in David Punter, The Literature of Terror, London: Longman, 1980.

© Roy Johnson 2011

Frankenstein – study resources

![]() Frankenstein – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

Frankenstein – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Frankenstein – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

Frankenstein – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

![]() Frankenstein – York Notes for students – Amazon UK

Frankenstein – York Notes for students – Amazon UK

![]() Frankenstein – York Notes for students – Amazon US

Frankenstein – York Notes for students – Amazon US

![]() Frankenstein – Spark Notes for students – Amazon UK

Frankenstein – Spark Notes for students – Amazon UK

![]() Frankenstein – Spark Notes for students – Amazon US

Frankenstein – Spark Notes for students – Amazon US

![]() Frankenstein – Cliffs Notes for students – Amazon UK

Frankenstein – Cliffs Notes for students – Amazon UK

![]() Frankenstein – Cliffs Notes for students – Amazon US

Frankenstein – Cliffs Notes for students – Amazon US

![]() Frankenstein – Norton Critical Editions – Amazon US

Frankenstein – Norton Critical Editions – Amazon US

![]() Frankenstein – 1994 Robert de Niro film – Amazon UK

Frankenstein – 1994 Robert de Niro film – Amazon UK

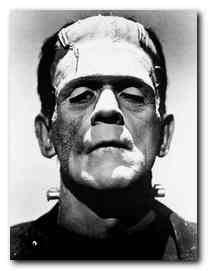

![]() Frankenstein – 1931 original film with Boris Karloff – Amazon UK

Frankenstein – 1931 original film with Boris Karloff – Amazon UK

![]() Young Frankenstein – 1974 Mel Brooks spoof – Amazon UK

Young Frankenstein – 1974 Mel Brooks spoof – Amazon UK

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories