tutorial, commentary, study resources, further reading

Lost Illusions (Illusions Perdues) (1837-1843) is one of Balzac’s greatest novels. It is in three parts and originally appeared in serial form. The three volumes which make up the whole work are The Two Poets (1837), A Great Man in Embryo (1839) and Eve and David (1843). The story begins in the provinces, moves to Paris, then returns to provincial life. There is also a sequel in the equally outstanding A Harlot High and Low (1838-1847).

Lost Illusions – commentary

Structure

The basic structure of the whole work is quite simple – but it has subtle and complex relationship to the main themes of the narrative.

Part One begins in the provinces – the south-west city of Angouleme, where two ambitious young friends David and Lucien are keen to pursue their ambitions. David stays at home to develop research into the printing industry and he lives a settled domestic life. Lucien takes the opposite approach and elopes with a married woman in search of literary fame in Paris (which the critic Walter Benjamin called ‘the capital of the nineteenth century’).

Part Two is entirely given up to Lucien’s rise and fall as a writer and a socialite. It presents an excoriating critique of journalism, newspapers, the theatre, and literary commerce in general. Lucien is feted and lionised on a very flimsy basis – largely on the strength of his good looks. He struggles to survive because he lacks income, and when his money runs out he is thrown on the social scrap heap.

Part Three returns to the provinces where these two themes are merged again. Lucien becomes the prodigal son back home: David is on the verge of commercial success. But both are struggling against superior forces. David is the innocent victim of legal and commercial sharks, and he is lucky to survive in time to collect his rightful legacy. Lucien makes matters worse for his family, and after deciding to commit suicide is rescued only by falling into the clutches of a master criminal.

At first sight, the three parts do not seem to be well integrated. Part Two is so long it appears to overwhelm the two adjacent parts. And the narrative in Part Three is forced to jump backwards chronologically to explain what has been happening in Angouleme whilst Lucien was in Paris. But there is an important compositional factor which should be taken into account on the issue of overall coherence.

Balzac’s writing method

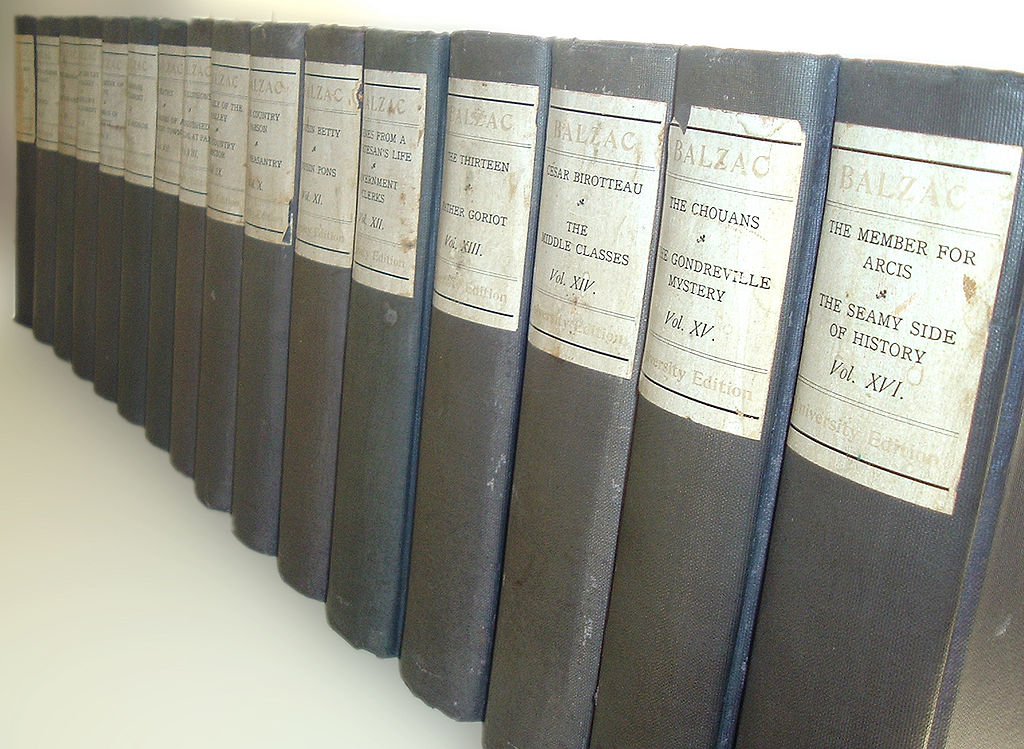

Balzac conceived and wrote his novels as the separate minor parts of a gigantic undertaking, La Comedie Humaine. This enormous compilation is an attempt to render the whole of French society and its development in the early part of the nineteenth century. It was a fictional world generated in what the critic George Saintsbury calls a ‘somewhat haphazard and arbitrary’ manner.

In any given year, Balzac might be working on two or even three separate parts of La Comedie Humaine. He would write (and publish) one novel, then later write another separate book dealing with a minor character from the first. It was rather like the completion of a huge literary jigsaw puzzle – one which progressively expanded the more he wrote.

To make matters more complex, he often changed the titles of the separate parts when they were transferred from serial publication in newspapers and magazines into single volume book format. All of these factors tend to militate against structural consistency. It is a miracle that La Comedie Humaine is as coherent as it is.

Names

There is an interesting reflection of social manners in the use of names throughout the novel. Lucien is the most obvious example. His name is not Lucien Rubempré, but Lucien Chardon. He has adopted a new patronymic because it disguises his origins as the son of a chemist, and the borrowed name has more aristocratic associations. But as soon as this deception is uncovered in fashionable society, he is ostracised as a parvenu and social climber – which is what he is.

Anais de Bargeton privately adopts the name of Louise for Lucien alone as a flirtatious link between them. She wants the pleasure of a mild affair without endangering her social reputation. She drops this affectation as soon they elope to Paris then go their separate ways

Baron Sixte du Chatelet, the dilettante ‘tax collector’ is a social fraud. He has adopted the ‘aristocratic particle’ de quite illegitimately to enhance his social standing. It is significant that Mme de Bargeton introduces him as Monsieur Chatelet at her salon in order to humiliate him before the other guests. However, it does not stop her eventually marrying him.

It is also worth noting in this regard that Balzac himself did exactly the same thing. He called himself Honore de Balzac without any legitimate claim to this distinction.

The business of literature

Balzac was intensely conscious of all aspects of what might be crudely termed ‘the book trade’. Lost Illusions contains scenes and even explanatory essays on all aspects of what is called ‘literary production’ – particularly its commercial elements. These range from the printing of books and even the production of the paper from which they are made.

It also includes the distribution of literary products and their reception into the marketplace. In addition he deals with the establishment of literary reputations via criticism and popular journalism, and the manner in which these are manipulated via very dubious commercial practices.

The novel starts with a study in printing technology as old miser Sechard sells his antiquated hand press equipment and cheats his son in doing so. There are full accounts of typography, setting type in cases, and the laborious process of proof-reading and editing text.

When Lucien reaches Paris he is confronted by all sorts of good and bad practices. His literary friends in the Cénacle have high ideals, but they live in poverty and earn their livings through odd-jobbing.

Perhaps the most amusing example of Balzac’s scathingly ironic view of the literary world comes when Lucien visits the offices of a newspaper. The naive young literary would-be expects to find grand premises, staffed by hard-working editors and creative journalists. Instead he finds a shabby one-man office concerned only with ‘subscriptions’. The newspaper is run by an editor who visits only occasionally, and it is written by journalists who do not exist. Copy for the publication is cobbled together on the fly from various sources, produced by writers unpaid and unseen.

Lucien’s friends in the Céacle and his colleague Etienne Lousteau give him warnings that represent Balzac’s extremely negative views on the business of journalism and the establishment of literary reputations. Reviewers accept bribes and produce their sycophantic criticism accordingly; they even extract favours from publishers and writers in exchange for favourable mention; and if refused, they will turn and pour scorn on the very same production.

The seedy side of the book trade is also exposed, with both reviewers and booksellers exhorting free copies from publishers, then selling them on at a profit. Wholesalers are motivated entirely by per item discounts and percentage reductions – with the actual value of the work in question completely disregarded.

The implications of all the literary activities to which Lucien is introduced are that books are a commodity like anything else such as cabbages or sacks of coal. Publishers are only interested in milking established literary reputations or whatever happens to be fashionable at the moment.

This seemingly cynical view of publishing is based on harsh economic realities. The publisher Dauriat explains the situation very clearly. He needs to make an advance payment to the author, then pay for good reviews in order to make the resulting sales profitable.

Obviously this is the sceptical-cum-cynical view of an author commenting on negative aspects of the business of publishing. But Balzac was himself a printer and a bookseller who knew the commercial aspects of the business first hand – from which he both profited and suffered. It is interesting to note that the system he exposes is virtually the same today – almost two centuries later.

Balzac knew this world very well – because he was a writer who also owned print production, and just like his idol Walter Scott, he virtually bankrupted himself by trying to combine the roles of writer, printer, and publisher. In fact, despite his immense success as a novelist, most of his earnings were swallowed up paying off debts – which were increased because of the extravagant life style he enjoyed.

Balzac is unrelenting in exposing the dubious and even corrupt relations that exist between journalists, theatre management, dramatists, actors, and the commercial enterprise in general. Authors pay to have their scripts considered; reviewers are instructed by newspaper editors how to report on theatrical productions; and organised groups of people (claqueurs and siffleurs) are paid to applaud or whistle at particular scenes and actors. Almost everywhere there is money oiling the wheels of reputations – and the last consideration of all is artistic merit.

Lucien’s review of a play featuring the eighteen year old actress Coralie who becomes his lover is hailed as a ground-breaking journalistic novelty. But it is nothing more than a plot summary with whimsical touches and entire paragraphs blatantly puffing up the two principal performers. The clear inference is that the feuilletons are pedalling second-rate material.

The business of business

Balzac was fascinated by the economic realities of life, and was keen to expose the detailed workings of material production, economic exchange, accountancy, and the system of banking and money which underpinned it all. Indeed, he even reproduces the solicitors’ accounts of David Sechard’s debts to show how legal fees have tripled the original amount of Lucien’s original three forged ‘bills’. (These are what we would now call ‘cheques’).

The scheming Cointet brothers illustrate perfectly the role of enterprises swallowing up their competitors to enlarge their own hold on the market. But they are not just printers: they are also paper manufacturers. These two essential parts of literary production had not yet become separated. Even more surprisingly, they also act as bankers.

It is not surprising that Balzac was much admired by Karl Marx, who believed that in works such as Lost Illusions the author exposed the essence of capitalism in all its moral, social, legal, and economic workings.

The realist novel

Balzac was one of the founders of what we now call the ‘realist novel’ – that is, fictional narratives which give an accurate and unsparing account of the society and its workings. A realist novel will normally include recognisable locations, credible characters, and dramas which reveal the way the world really operates. They also commonly offer a sharply critical view of social conflicts, and are prepared to explore topics such as corruption, poverty, crime, and other negative aspects of human behaviour.

Balzac creates a detailed and comprehensive account of the social milieu in which his dramas take place. The beginning of Illusions Perdues is set in the provincial location of Angouleme, and he provides what is virtually a sociological description of the city, its geography and economic history, plus the class stratification of its inhabitants.

This might at first seem like mere scene setting, but it demonstrates the provincial world from which the protagonist Lucien Chardon wishes to escape in his quest for fame in the capital, Paris. It also reveals how even the topography of a location can have an influence on the people who live there

In addition to this socio-economic understanding of society, Balzac also has an incredibly detailed perception of its physical details and their implications. His description of a house both reinforces the realism of its presentation (rather like a Dutch interior painting) and shows that he is vitally aware of the surfaces, the textures, colours, and the fabrics of the world in which his characters live.

When Lucien makes his first visit to Mme de Bargeton, he is overawed by entering a level of society far above his own. But the narrative reveals Balzac’s critical view of the Bargetons’ down-at-heel aspirations to domestic grandeur:

Lucien walked up the old staircase with chestnut banisters, the steps of which ceased to be of stone after the first flight. Crossing a shabby little anteroom and a large drawing-room, dimly lit, he found his sovereign lady in a small salon with wainscots of wood, carved in eighteenth-century style and painted grey. The upper parts of the door were painted in camaieu. The panelling was decorated with old red damask, poorly matched. The old-fashioned furniture was apologetically concealed under loose covers in red and white check. The poet caught sight of Madame de Bargeton seated on a couch with a thinly-padded quilt, in front of a round table covered with green baize, on which an old-fashioned, two-candled sconce with a paper shade above it cast its light.

Lost Illusions – study resources

![]() Lost Illusions – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Lost Illusions – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Lost Illusions – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Lost Illusions – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Lost Illusions – Random House – Amazon UK

Lost Illusions – Random House – Amazon UK

![]() Lost Illusions – Random House – Amazon US

Lost Illusions – Random House – Amazon US

![]() Illusions perdues – Wikipedia

Illusions perdues – Wikipedia

All characters in La Comedie Humaine

Cambridge Companion to Balzac – Cambridge UP – Amazon UK

Lost Illusions – plot summary

Part I – The Two Poets

Old miser Sechard sells an out-of-date printing press to his son David, who employs his poor school friend Lucien Chardon as a proof-reader. The two young men are soul mates with idealistic cultural and intellectual ambitions.

Lucien is introduced to local Angouleme society lioness Mme de Bargeton by her admirer the Baron Sixte du Chatelet. Lucien is flattered and falls in love with her. She decides to cultivate and promote him as a poet, and persuades him to change his name to Rubempré. Lucien would like David to share his good fortune, but his friend turns down the offer. David is very shyly in love with Lucien’s sister Eve.

Lucien delivers a poetry recital amongst the Angouleme elite, who are bored and snobbishly insult him. David proposes marriage to Eve, with a view to creating a business that can support Lucien in his ambition. David delivers a lecture on paper-making techniques to Eve in order to explain his plans. David’s miserly father refuses to help him improve the house he lives in.

Lucien develops his affair with Mme de Bargeton, and lives off the earnings of his mother, his sister, and David. But Lucien is frustrated by the refusal of Nais to give in to his romantic demands. Du Chatelet spreads rumours about the affair and eventually a duel is fought. Nais decides to leave for Paris and demands that Lucien go with her. Lucien borrows more money from David and his family.

Part II – A Great Man in Embryo

Du Chatelet follows Anais and Lucien to Paris, advising her not to compromise herself. Lucien spends money he cannot afford on fashionable clothes, but at the opera he becomes disenchanted with Anais – and she with him. He is ostracised when it is revealed he is a chemist’s son. Du Chatelet acts ambiguously but gives him sound advice. Lucien decides to renounce society and joins a group of poor Bohemian artists, convinced he will soon become rich and famous.

Lucien begins to approach booksellers with his novel and collection of poems. He finds a publisher but rejects the terms he is offered. Fellow writer Daniel d’Arthez encourages him and advises him to avoid journalism. The fellowship club together to give Lucien support, and he continues to accept money from his family.

Lucien decides he will take the risk and attempt to earn a living from journalism. He visits a newspaper office, only to discover that there is almost nobody in charge. He shows his collection of sonnets to Etienne Lousteau, who warns him against the corrupt world of journalism and the shabby end of book trading and criticism.

Lousteau takes Lucien into the grubby but fashionable world of journalism and the book trade in the wooden galleries of the Palais-Royal. A publisher pours scorn on poetry but agrees to read Lucien’s work. Lousteau takes Lucien to the theatre where they mix with actresses and critics.

Lousteau explains the complex financial networks of patronage, bribes, backstabbing, and ownership that connects theatre management, reviewers, and newspaper editors. He holds out a tempting but tainted offer to Lucien, who is suddenly the object of interest to the young actress Coralie. Lucien writes a review of the play and is immediately invited to join the staff of a newspaper.

The journalists enjoy a debauched dinner party with the actresses, during which newspapers are criticised by the very people who write for them. The actress Coralie takes Lucien back home where he remains for two days in the sumptuous apartment maintained by her rich ‘protector’ Camusot.

After improving the manuscript of his novel, the Cénacle reproach Lucien for becoming a journalist. His relationship with Coralie is exposed by her protector Camusot, who reluctantly condones it. Lucien attends a newspaper editorial meeting where they discuss the invention of canards, but his collection of sonnets is still refused by publisher Dauriat.

Lousteaux instructs him on how to write negative critical articles. Lucien writes a damning critique of a Dauriat publication, which prompts Dauriat to buy Lucien’s poems outright and harness his services. Lucien then writes another article praising the same book. He also writes a column satirising Mme de Bargeton and Baron du Chatelet.

Lucien’s theatre reviews are heavily edited to suit the theatre’s relationship with the newspapers. He is introduced to the organisation of claques, siffleurs, and re-selling of complementary seats. Lucien and Coralie throw a lavish dinner party at which his success as a journalist is ‘crowned’.

Lucien mixes in the aristocratic society that once shunned him. He is encouraged to get rid of Coralie, join the political conservatives, and apply for royal permission to adopt the name Rubempré. He is implored to stop attacking Mme de Bargeton, whom he meets again and who flatters him.

Lucien lives beyond his means, runs up debts, and does less and less work. He moves away from literature towards politics. Lousteau explains the journalistic system of blackmailing celebrities who have something to hide.

Lucien unsuccessfully tries to raise money, and gambles away the little he has. The Céacle warns him not to join the Royalists, but he ignores them. He becomes an object of ridicule and a symbol of betrayal. He pays for good reviews of Coralie’s new performance and is forced to write a damning review of d’Arthez’ excellent new book. Coralie fails in her new part, and Lucien is refused his promotion to the name Rubempré.

His review arguments spill over into a duel, in which he is injured. He becomes bankrupt and when Coralie dies he hasn’t enough money to pay for her funeral. He forges bills in his brother-in-law’s name, pays off his debts, and decides to go back home.

Part III – An Inventor’s Tribulations

Lucien arrives back in the Angouleme region to discover that David and the family have been plunged into debt because of the forged bills.

Previously, Eve took over the press whilst David pursued his dream of new paper making techniques. They enter into a dubious business relationship with rival printers Cointet. Eve is shocked to learn the truth about her brother Lucien’s degenerate life in Paris. Then his forged bills arrive in Angouleme.

David and Eve cannot meet the bill, which has been loaded with extra legal charges. The bill is sent back to Lucien, who is advised to delay matters – which merely adds further costs. David consults lawyer Petit-Claud who is in the pay of the Cointet brothers. Finally the legal costs are three times the size of the original debt. Petit-Claud inflames tensions between David and old Sechard, who still refuses to help his son, who goes into hiding to avoid arrest.

David succeeds with his new invention. Both the Cointets and his own father want to know his secret. Petit-Claud ties to arrange a financially advantageous marriage. At this point Lucien reaches home.

Lucien is accepted back into the family – but with reservations on both sides. He is suddenly celebrated as a writer in the local press – but the adulation has been artificially arranged by Petit-Claud.

Petit-Claud pretends to assist Lucien, whilst secretly plotting against him. Lucien orders stylish new clothes from Paris and attends a grand celebration held in his honour. He plans to flatter Louise again and wangle a research grant for David. But David is tricked with a forged letter to emerge from hiding and is arrested.

Lucien decides to commit suicide but when he leaves home he is dissuaded by a Spanish priest Carlos Herrera (Vautrin the arch-criminal in disguise). Vautrin promises him financial support in exchange for Lucien’s allegiance.

Meanwhile Petit-Claud persuades Eve and David to reach a compromise with the Cointets, who enforce a disadvantageous business deal. Lucien’s money arrives a day too late to save them. Cointet goes on to become rich; David gives up his experiments and inherits his father’s fortune. Petit-Claud advances his legal career. For news of Lucien the reader is referred to the next instalment of the Comedie Humaine, which was to be A Harlot High and Low.

Illusions Perdues – characters

| Jerome-Nicolas Sechard | a miserly printing press and vineyard owner |

| David Sechard | his son, a typographist with scientific ambitions |

| Lucien Chardon | David’s poor school friend, a handsome would-be writer |

| Mme Anais de Bargeton | an attractive social lioness with snobbish ambitions |

| Baron Sixte du Chatelet | a dilettante tax collector with social ambitions |

| Daniel d’Arthez | a talented writer, Lucien’s close friend in the artistic fellowship |

| Etienne Lousteau | a successful young freelance journalist |

| Coralie | an eighteen year old Jewish actress |

| Camusot | a rich and retired silk merchant and Coralie’s ‘protector’ |

| Dauriat | a publisher at Palais-Royale |

| Boniface Cointet | a paper-maker, printer, and banker in Angouleme |

| Cerizet | David’s duplicitous employee |

| Pierre Petit-Claud | an ambitious and scheming provincial solicitor |

| Vautrin | a master criminal, ex-convict, and homosexual (real name Jaques Collin) |

© Roy Johnson 2018

More on Honore de Balzac

More on literary studies