tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

Benito Cereno (1856) was published in the collection The Piazza Tales which Melville wrote after the disappointing reception of his masterpiece Moby Dick which had appeared in 1851. Like many of his other works Benito Cereno is rich in ambiguities, symbolism, and profound meanings beneath its surface narrative. It’s based upon a documentary record of historical events written by the real Amasa Delano in 1817, but of course Melville dramatises ‘the capture of a ship’ to make it richer in suggestive allusion.

The events of the story are an exercise in sustained irony (a device also used by another mariner-novelist, Joseph Conrad). The first time reader is invited to see circumstances exactly as Captain Amasa Delano encounters them, as he goes from his own ship to offer help to a striken fellow captain. Everything he confronts is baffling, contradictory, and uncertain. He struggles to interpret what he finds, but is hampered by his own inclination to believe the best of everybody he meets. The truth of the situation is only revealed very dramatically at the very last minute.

Benito Cereno – critical commentary

Narrative

Most of Benito Cereno is told from the point of view of Amasa Delano. We encounter the puzzling conditions on board the San Dominick as he does; we have things presented to us as he sees them, and we do not have any other point of view by which to achieve a fictional triangulation to assess what is going on (except in a second or subsequent reading).

Melville’s narrative technique sometimes takes us into Delano’s thoughts, almost in a form of interior monologue, and at times Delano even addresses himself, as if thinking out loud.

The novella is set in 1799 – only a few years after the start of the slave uprising in San Domingo (now Haiti).

Present day readers cannot fail to notice that two of the Spanish crew of the San Dominick are killed by what is now called ‘friendly fire’. That is, when the Americans attack the San Dominick in order to recapture it from the rebel slaves, they mistakenly kill two Spanish sailors who are on their own side in the conflict.

The Novella

Benito Cereno was published as part of The Piazza Tales (1856); it is about 25,000 words long; and it could be regarded as a long short story – but it fulfils many of the criteria for being classed as a novella.

Unity of place

Almost the whole of the story takes place in one location – on board the San Dominick. Captain Delano goes to inspect the ship, climbs aboard alone, and stays there until his boat comes (for the second time) to take him back to the Bachelor’s Delight.

Even the depositions in court (which constitute the ‘explanation’ for what happened) are scenes which took place on board the San Dominick prior to its encounter with the Bachelor’s Delight.

Unity of action

The essential drama of the story unfolds in more or less one continuous action. Moreover, these events are compressed into the shortest possible chronological sequence – less than one whole day. Captain Delano goes on board the San Dominick in the morning, He takes a ‘frugal’ lunch with Captain Cereno. And when his boat ‘Rover’ comes back for the second time to take him back, he returns to the Bachelor’s Delight. The action of the story is concentrated in an almost Aristotelian manner to produce unity of time and action.

Unity of atmosphere

The whole of the narrative is shrouded in mists, becalmed seas, and symbols of mystery and ambiguity. The skies are gray, the San Dominick looks like a ‘white-washed monastery after a thunder-storm’. Nothing is quite what it seems. Delano is constantly baffled by the contradictions and mysteries he encounters. The ship’s figurehead is wrapped in a shroud; Captain Cereno shows no gratitude for being given help on his doomed ship; the slave Atufal is still in chains when others have been released. The tension and sense of menace increase until the moment in the ‘Rover’ that Captain Delano realises what is happening.

Even the events described in the court depositions intensify this atmospheric unity – since they enhance the macabre and grotesque nature of what has taken place aboard the doomed ship.

Unity of character

There are a number of minor named characters in the story – but essentially the whole drama is focussed on three people – Delano, Cereno, and Babo. Captain Delano is the naive, good natured protagonist, seeking to interpret the ambiguities of the world he encounters – and failing to do so at every turn until the truth is finally thrust upon him. Cereno is a good man totally in thrall to an evil power – almost a warning of what Delano’s naivety can lead to if he doesn’t wake up. And Babo is that evil power incarnate. He has been ruthless in taking control of the San Dominick; he has murdered his former ‘owner’, and had his skeleton nailed to the prow with an ironic warning inscribed ‘Follow your leader’. Babo orchestrates events on board the ship, including the menacing shave for Cereno.

The main issue

The event is one from many curious incidents recounted by mariners and others from events at sea. Melville’s work as a novelist draws on many of these recorded events. But these particular events are more than just curious: they embrace large scale political issues. The relationship between America, Europe, and colonialism for instance. America at the time of the story had just fought a war of independence, changing itself from a colony of Britain to an independent state. It had also been engaged in conflicts with England, Spain, and France regarding the slave trade.

The first successful slave uprising had started in San Domingo (now Haiti) in 1791. Slavery was not abolished formally in Great Britain until 1833 and in the USA until 1865, and it is interesting to note that the practice of slavery was first begun in the Spanish colonies around 1500.

So the story does not deal with small scale accidental matters, but forces of great geo-political importance. Benito Cereno, a Spaniard is in charge of a ship whose primary cargo is slaves, ‘owned’ by another Spaniard (Alexandro Aranda).

We do not know where the slaves are from, but it is significant that immediately after seizing control of the San Dominick the rebellion leader Babo wants to be taken back to Senegal – on the west coast of Africa. In other words, he has enough ‘race memory’ to know where he might have originally come from.

Benito Cereno – study resources

![]() Benito Cereno – Oxford World Classics edition

Benito Cereno – Oxford World Classics edition

![]() Benito Cereno – Dover Thrift edition

Benito Cereno – Dover Thrift edition

![]() Benito Cereno – Penguin Classics edition

Benito Cereno – Penguin Classics edition

![]() Benito Cereno – Cliffs Notes

Benito Cereno – Cliffs Notes

![]() Benito Cereno – Norton Critical Editions

Benito Cereno – Norton Critical Editions

![]() Benito Cereno – free eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

Benito Cereno – free eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() Benito Cereno – Kindle eBook edition

Benito Cereno – Kindle eBook edition

Benito Cereno – plot summary

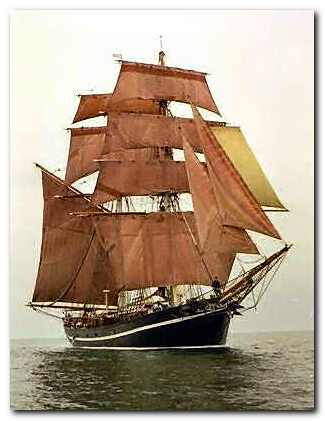

Amasa Delano is the good-natured captain of the Bachelor’s Delight, an American sealing ship sailing off the western coast of Chile in 1799. His ship is approached by another, the San Dominick, which is drifting aimlessly and appears like a ghost ship. Delano goes to inspect it and discovers a puzzling state of affairs on board. The captain, Don Benito Cereno appears to be in a state of collapse, there are very few crew members on board, and a cargo of ‘negro slaves’ has been let loose to act in a somewhat menacing fashion.

Benito Cereno explains to Delano that most of the crew were lost during terrible storms at sea, which also damaged the ship; but his explanation doesn’t entirely satisfy Delano, who nevertheless sends his boat back to the Bachelor’s Delight to fetch emergency supplies for the survivors.

Throughout Delano’s visit to the San Dominick, Benito Cereno is accompanied by a very attentive negro servant who never leaves his side. Indeed, he is so solicitous of his master’s wellbeing that Delano at one point offers to buy him for his own use.

Delano continues to be disturbed by the inexplicable goings-on around him – such as a group of slaves who are sharpening hatchets, and Benito Cereno’s lack of thanks for the assistance he is being offered. But Delano repeatedly interprets what he see in a positive and generous light.

When the relief supplies have been distributed, Delano sends the boat back to the Bachelor’s Delight, leaving him alone with the members of the San Dominick. He watches Babo shave Benito Cereno, then dines with them, the servant being present throughout. Delano then takes charge of the San Dominick and steers it towards the Bachelor’s Delight in a safe mooring. He invites Benito Cereno to join him on board for coffee – but Benito Cereno refuses.

When a boat arrives to collect him Delano is still puzzled by Cereno’s coldness and lack of response to a generous offer of help. But when Delano gets into the boat, Cereno suddenly leaps from the San Dominick, closely followed by Babo bearing a knife. Delano is convinced they are going to kill him, but it quickly becomes apparent that Babo intends to kill Benito Cereno.

Babo is seized, they regain the Bachelor’s Delight, and then a party of men sets off and recaptures the San Dominick, which is taken to investigative governmental courts in Lima, Peru.

The second part of the story is a sequence of depositions made to the court which record the true sequence of events regarding the San Dominick and the fate of those on board. Starting with a general revolt of the ‘cargo’ of slaves, Babo and his henchman Atufal take charge and command Benito Cereno to sail for Senegal, which is half way round the other side of the world, in West Africa. Members of the Spanish crew are murdered or thrown alive into the sea.

Alexandro Aranda (the ‘owner’ of the slaves) is murdered, and his skeleton is nailed to the front of the ship as a figurehead. After storms and damage to the ship, they arrive at Santa Maria at the same time as the Bachelor’s Delight. Babo arranges the deceptive appearance on board the San Dominick and threatens everybody on board with instant death if they reveal the truth of what has happened. He even puts Atufal in chains as a deceptive ploy, and plans to seize arms and capture the Bachelor’s Delight.

The tribunal recognises Babo as the principal culprit, and sentences him to death. Benito Cereno retreats to a monastery, where he dies three months later.

Principal characters

| Amasa Delano | American captain of the Bachelor’s Delight, a sealing and general trading ship |

| Don Benito Cereno | young captain of the San Dominick, a first-calss Spanish general trading ship |

| Babo | former slave and ‘attendant’ to Benito Cereno |

| Don Alexandro Aranda | ‘owner’ of the slave ‘cargo’ on the San Dominick |

| Atufal | Babo’s assistant, a slave and ‘former king’ |

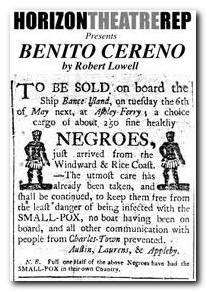

Theatrical adaptation

Poster for 1965 play by the poet Robert Lowell

Further reading

John Bryant (ed), A Companion to Melville Studies, Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 1986.

Robert E. Burkholder, Critical Essays on Melville’s ‘Benito Cereno’, Boston: G.K. Hall, 1992.

Andrew Delbanco, Melville: His World and Work, New York: Random House, 2006.

William B. Dillingham, Melville’s Short Fiction 1853-1856, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1977.

Marvin Fisher, Going Under: Melville’s Short Fiction and American 1850s, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

Richard Harter Fogle, Melville’s Shorter Tales, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960.

Kevin J. Haynes, The Cambridge Introduction to Herman Melville, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007

Carolyn L. Karcher, Shadow Over the Promised Land: Slavery, Race, and Violence in Melville’s America, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980

Robert S. Levine, Conspiracy and Romance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Robert Milder, Exiled Royalties: Melville and the Life We Imagine, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Lea Bertani Vozar Newman, A Reader’s Guide to the Short Stories of Herman Melville, Boston: G.K. Hall, 1986.

Elizabeth Schultz, Melville & Woman, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006

© Roy Johnson 2011

William (Billy) Budd is a handsome and popular young sailor, serving on a merchant ship The Rights of Man. He a great favourite of his ship’s master, Captain Graveling. In 1897 however, Billy is impressed into service on the HMS Bellipotent which is commanded by the aristocratic Edward Fairfax (‘Starry’) Vere. Billy is a figure of innocence and good nature. He is an illiterate foundling (an abandoned and presumably illegitimate child) and is popular with other crew members. But the ship’s master-at-arms John Claggart is fuelled by a malevolent impulse to harm Billy. He reports him to the captain, falsely accusing him of fomenting a mutiny.

William (Billy) Budd is a handsome and popular young sailor, serving on a merchant ship The Rights of Man. He a great favourite of his ship’s master, Captain Graveling. In 1897 however, Billy is impressed into service on the HMS Bellipotent which is commanded by the aristocratic Edward Fairfax (‘Starry’) Vere. Billy is a figure of innocence and good nature. He is an illiterate foundling (an abandoned and presumably illegitimate child) and is popular with other crew members. But the ship’s master-at-arms John Claggart is fuelled by a malevolent impulse to harm Billy. He reports him to the captain, falsely accusing him of fomenting a mutiny.