how to check your work for publication

Proofreading and making corrections is the very last stage of preparing a document for publication. At this point the main content of what you have written should already be finalised – checked for accuracy of content, grammar, spelling, completeness, and layout.

Proofreading looks at the presentation of the text in great detail – mainly for matters of bibliographic and typographic consistency. You will be checking on features in the document such as the following, checking for regularity and consistency.

- Capitalization of headings

- Font size and style

- Spacing between paragraphs

- Regularity of indentation

- Use of italics and bold

- Page numbering

- Hierarchy of headings

Word-processors

Word-processors take a lot of the strain out of proofreading. Spell-checking will be easy, and matters such as letter-spacing and line-spacing are automatically regularised.

The basic appearance of writing on the page (or screen) is also controlled automatically.

For instance, text justification can be set as left-aligned or fully-justified. Left-aligned text creates regular spaces between words, but the right-hand edge of the text will be uneven – which is called ‘ragged right’ or ‘unjustified’. Choice of justification will be determined by the document type.

Fully-justified text creates an even left and right-hand margin – but there may be uneven spaces between words. These gaps can cause what are called ‘rivers’ of white space to appear in the text. These are created by irregular spaces between words.

Word-processors can usually give you control of a number of features in a document. These can be set automatically, and therefore eliminated from the number of tasks involved in proofreading.

- Hyphenation on and off

- Picture captions

- Headers and footers

- Size of titles and sub-titles

- Treatment of numbers

- Use of quotation marks

- Bibliographic citations

- Punctuation of lists

- Page numbering

- Hierarchy of headings

Proofreading example

The following extract contains several elements that require an editorial decision. That is, where choices of house style must be made about the use of capitals, quotations, commas, numbers, and so on. The passage does not contain any mistakes.

In 1539 the monastery was ‘dissolved’, and the Abbot, in distress of mind—recognising that there was no alternative but to co-operate with the King’s officers—blessed the monks (they numbered fifty-seven), prayed with them, and sent them out from the abbey gates to follow their vocation in the world.

There are eight issues here that call for editorial decisions on the styles used in presentation of text.

- Dates are shown using numbers [1539]

- Quotations are shown using single quote marks [‘dissolved’]

- Capitals used for titles of specific office holders [Abbot, King]

- No capitals for informal references to institutions [monastery]

- Em-dash used for parenthetical remarks [—]

- Use of -ise not -ize for endings [recognising]

- Numbers up to 100 shown in words [fifty-seven]

- Use of the serial comma

These details make all the difference between an amateur attempt at document production, and a successful and professional piece of work.

Inconsistencies in any of these style issues will cause problems for the reader: For instance, Abbot is an official title, whereas abbot is merely a term to describe the type of clergyman.

House style

House style is the term given to a set of conventions for the presentation of printed documents in an organisation.

The conventions might be formalised as a printed style guide [The Economist Style Guide, New Hart’s Rules] or they might be an informal set of guidelines governed by tradition and convenience.

Any company that wishes to appear professional will have its own house style. It can decide on its own protocols, some of which might contravene traditional practices.

The organisation could be any form of business or official body:

- Publishing company [a newspaper or magazine]

- Government body [Department of Education]

- Legal institution [Courts of Justice]

- Commercial enterprise [IBM, Amazon]

These organisations have a house style so that there will be consistency and uniformity in the way they present themselves visually to the world.

They might wish to specify the size and font style of their titles, headings, and sub-headings. They are likely to specify how graphics are to be displayed, and they might have policies regarding the use of foreign or emotionally loaded terms.

For instance, newspapers have to make policy decisions on how to describe a dictator’s staff – as a ‘government’ or a ‘regime’.

Proofreading method

The first choice you will need to make is between proofreading on screen or on paper. Many people find it easier to spot mistakes if they print out a document and do the editing and proofreading by hand.

The advantages and disadvantages of the two approaches are essentially as follows.

Editing directly on screen has the advantage that you do not have to transfer corrections from paper to screen. The disadvantages are that any changes you make will over-write the original text. It is also harder to see small details on screen than on paper.

It is true that you can save each separate version of an edited text. This means you have a record of your earlier versions. But each new version leads deeper and deeper into a labyrinth of complexities when making comparisons to select the best.

Editing by hand on a printed document has the disadvantage that all corrections will need to be re-typed, The main advantage is that the original text will still be visible if second thoughts arise.

For details of the advantages and disadvantages of the two approaches, see Editing documents on screen and paper.

You might find it difficult to concentrate on all the small details of proofreading. This is because it is very tiring to hold a number of issues in your head at the same time.

If this is the case, try this tip to make things easier. Split the task into a number of separate stages. Proofread for just one feature at a time. Go through the work checking only on your use of capitals in headings; then go back again to check only on your use of italics, and so on. Use the list of features below as a guide.

| Abbreviations | Full stops |

| Apostrophes | Hyphens |

| Bold | Italics |

| Brackets | Numbers |

| Capital letters | Quotation marks |

| Colons | Semicolons |

| Commas | Spelling |

| Dates | Titles |

Further detailed guidelines on

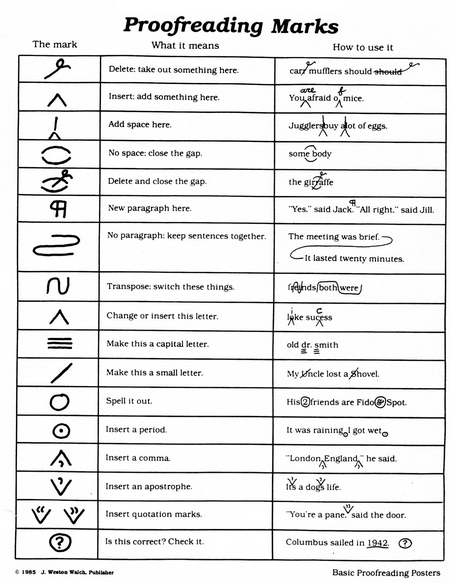

Proofreading marks

There is also an elaborate system of marks used in professional proofreading for correcting the proofs of printed documents. These are for the specialist, and it is unlikely that the average writer would need to use them. But they might be of interest.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills