This book examines some of the fundamental questions about writing. What is it? What is it for? How is it related to literacy? It’s also about the philosophy of information storage and transmission. A great deal of what Albertine Gaur has to say centres on the historic development of different writing systems. She shows how they emerged from numbering systems and pictographic records. She covers numeric as well as pictorial and non-linguistic forms of writing in a historical and cultural range which is simply breathtaking.

It’s a scholarly book, pitched at a fairly high intellectual level [well, I found it so] in which terms are left unexplained and you have to keep up with a compact and rapid manner of delivery. She admits that her particular approach of posing questions about the nature of writing raises problems rather than supplying answers, but in identifying gaps in our knowledge she challenges some widespread assumptions.

It’s a scholarly book, pitched at a fairly high intellectual level [well, I found it so] in which terms are left unexplained and you have to keep up with a compact and rapid manner of delivery. She admits that her particular approach of posing questions about the nature of writing raises problems rather than supplying answers, but in identifying gaps in our knowledge she challenges some widespread assumptions.

For instance, she raises a serious criticism of the UK’s current National Literacy Strategy based on what she sees as a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of the phoneme – the supposed smallest possible unit in the sound system of any language.

Equally tenuous is the connection between language and writing. Speculation, for example, about how well (or how badly) the alphabet represents the English language is more or less spurious for the simple reason that the alphabet was never meant to write English in the first place. The present alphabet goes back some three thousand years via Etruscan and Roman forms of writing to a Greek alphabet which was, in turn, simply an adaptation of the Phoenician consonant script, to a time when the English language did not even exist.

The part of the book I found most interesting was the account of how contemporary writing systems (the Roman alphabet) developed historically from a common Proto-Semitic script. This leads into a consideration of why certain writing systems succeed (the rather difficult Chinese for instance) whereas others don’t. It usually comes down to politics.

Some people used to believe in a monogenesis theory of writing, rather like the monotheistic religious belief – one source, one author, one instant moment of creation. She comprehensively debunks this myth, but then very broadmindedly goes on to discuss examples of people who have actually invented scripts to fit spoken languages.

There are fascinating reflections which arise from asking such apparently simple but profound questions as ‘What is a book?’ The answers to this question, which involve the long transition from the scroll to the collection of separate pages called a codex reveals the origin of much of which we now take for granted: titles, tables of contents, pages, and page numbers.

It’s beautifully illustrated with pictures of rare texts, unusual scripts and printings, and examples of writing systems from all over the globe, Albertine Gaur was formerly head of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books at the British Library. It’s quite clear that she knows these objects intimately, and this book is her attempt to share her knowledge and enthusiasm for them. Anyone who is interested in the philosophy of writing or the book as a physical object will profit from the encounter.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Albertine Gaur, Literacy and The Politics of Writing, Bristol: Intellect, 2000, pp.188, ISBN 1904705065

More on theory

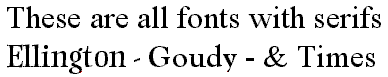

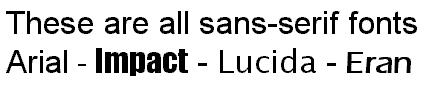

More on typography

More on digital media