tutorial, commentary study resources, commentary, criticism

The Ambassadors was written between October 1900 and July 1901, and initially appeared as a serial running in the North American Review. Its first appearance as a single novel was in the autumn of 1903 by Methuen in London and Harpers in New York.

The novel comes from what is called James’s ‘late period’. The writing is mannered, baroque, complex, and focused intently on the psychological relationships between his characters. There is very little ‘plot’ here in the conventional sense. Much of the interest in the narrative is centred on the limitations of the principal character, from whose point of view the story is told. Lambert Strether is a morally upright, middle-aged American who feels that life has passed him by. He wants to do the right thing, but finds himself somewhat out of his depth when he visits Paris – which Walter Benjamin called ‘the capital of the nineteenth century’.

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

The Ambassadors – critical commentary

The Ambassadors is narrated in third person omniscient mode, almost entirely from Lambert Strether’s point of view. Just occasionally, James lapses into first person (plural) mode, speaking of Strether as ‘our friend’. The novel also follows a structural pattern, in keeping with its first publication as a serial, of taking each section (‘Book Tenth’) up to a point immediately preceding a dramatic climax, then beginning the next section after the dramatic event has taken place. The sequence of events is then re-traced retrospectively, with Strether reflecting endlessly on various possible nuances of behaviour.

In fact there is very little action in the novel at all. It consists of a series of conversations Strether has with other characters, punctuated by evocations of location (Chester, London, Paris). And the conversations consist almost entirely of the interlocutors trying to interpret or second-guess the psychological motivation and intentions of other characters in the plot.

These topics remain obscure for a number of reasons. The first is that almost all social intercourse is constrained by an elaborate set of protocols whereby everybody is forced to be extremely polite in their dealings with others. Nothing concrete or specific can be discussed openly, and all conversations are shrouded in mists of subtle inference, hints, allusions, and guesswork.

The second is that most of the characters talk to each other in a manner which is almost a continuation of James’s own style as narrator. Nobody speaks in the concrete and the here and now as most human beings normally do. They use elaborate metaphors and allusions, talking about other characters and the events of the novel (in so far as there are any) in oblique, orotund terms:

‘Ah,’ Miss Goostrey sighed, ‘the name of the good American is as easily given as taken away! What is it, to begin with, to be one, and what’s the extraordinary hurry? Surely nothing that’s so pressing was ever so little defined. It’s such an order, really, that before we cook you the dish we must at least have our receipt. Besides, the poor chicks have time! What I’ve seen so often spoiled,’ she pursued, ‘is the happy attitude itself, the state of faith and—what shall I call it?—the sense of beauty.’

There is a third reason that makes it difficult for the reader to form judgements about the events and the characters of the plot. James has them refer to each other as ‘tremendous…wonderful…magnificent… [and] immense’ – but none of the characters is shown or dramatised doing anything by which we can form an opinion on these matters. Everything is filtered through the eyes of Strether or James – and it is often difficult to see where one begins and the other ends.

There is also a great deal of concealment going on in the novel. Quite apart from the nature of the relationship between Chad Newsome and Mdme de Vionnet being concealed from Strether, it is also concealed from him by Maria Goostrey. She conceals her desire for Strether himself out of deference to his theoretical attachment to Mrs Newsome. This is not apparent to Strether until the end of the novel, though it can be perceived by the reader. This is a mild form of dramatic irony that James offers as easily digestible crumbs to readers whilst they grapple with the larger issues of obfuscation.

Moreover there is a larger form of concealment practised by James himself. As the author and the outer narrator he is in possession of all the facts from the very start of the novel, and occasionally shows his hand by mentioning that something will be revealed later (‘two or three incidents with which we have yet to make acquaintance’). But he deliberately obfuscates events and motives in a way which is likely to strain the patience of all but the most tolerant readers.

Homo-eroticism

Strether is a typical figure from James’s late works – a middle-aged man taking stock of his somewhat emotionally empty life. He has lost his wife and child; his only social function is acting as the titular editor of a literary magazine which is funded by Mrs Newsome (and doesn’t sell many copies); and he is very conscious that life seems to have passed him by.

“I seem to have a life only for other people … it’s as if the train had fairly waited at the station for me without my having the gumption to know it was there. Now I hear the faint receding whistle miles and miles down the line”

There are also a number of homo-erotic undertones to the novel – as there were in the latter part of James’s own life. Both Strether and Waymarsh have removed themselves from intimate contact with women (Strether’s wife is dead, and Waymarsh is separated). They travel together, and they share a certain scepticism regarding the opposite sex – all of whom are regarded as potential predators. In an early scene Strether visits Waymarsh whilst he is in bed. Waymarsh tells Strether ‘You’re a very attractive man’ and they joke about being married.

He looked across the box at his friend; their eyes met; something queer and stiff, something that bore on the situation but that it was better not to touch, passed in silence between them.

In fact whenever the male characters in the novel meet each other, there is a great deal of eye contact and touching of the knee, the hand, the shoulder. Although he is technically engaged to Mrs Newsome, Strether gradually drifts away from her during the novel and spends all his time in concern about her young son, who he describes in rhapsodic terms.

Strether is also pursued by Maria Goostrey, but when she finally makes him an offer of marriage, he rejects the opportunity on grounds that he wouldn’t wish to be seen profiting personally from the errand on which he has been sent. In other words, he rationalises his fear of heterosexual intimacy on grounds of a lofty self-denying moral principle.

Study resources

![]() The Ambassadors – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Ambassadors – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Ambassadors – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Ambassadors – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Ambassadors – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Ambassadors – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Ambassadors – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Ambassadors – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Ambassadors – Dover Thrift – Amazon UK

The Ambassadors – Dover Thrift – Amazon UK

![]() The Ambassadors – Dover Thrift – Amazon US

The Ambassadors – Dover Thrift – Amazon US

![]() The Ambassadors – Kindle eBook (includes sixty James books)

The Ambassadors – Kindle eBook (includes sixty James books)

![]() The Ambassadors – York Notes – Amazon UK

The Ambassadors – York Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Ambassadors – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

The Ambassadors – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Ambassadors – etext of the 1909 edition

The Ambassadors – etext of the 1909 edition

![]() The Ambassadors – audioBook edition

The Ambassadors – audioBook edition

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James – biographical notes

Henry James – biographical notes

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, web links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, web links, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, web links, study resources

The Ambassadors – characters

| Lewis Lambert Strether | 55 year old American widower, magazine ‘editor’, engaged to Mrs Newsome |

| Mr Waymarsh | a rich American lawyer, separated from his wife, Strether’s travelling companion |

| Miss Maria Goostrey | American woman living in Paris who offers herself as ‘a guide to Europe’ |

| Mrs Newsome | a rich American widow |

| Chadwick Newsome | a 28 year old heir to his father’s successful business |

| Sarah Newsome | Chad’s 30 year old sister, married to Jim Pocock |

| Jim Pocock | a leading Woolett business man, married to Chad’s sister |

| Mamie Pocock | Jim Pockock’s young sister |

| John Little Bilham | an American enthusiast about art, friend of Chad’s |

| Miss Barrace | a slightly eccentric American spinster and commentator on events |

| Signor Gloriani | a famous Italian sculptor |

| Countess Marie de Vionnet | a society beauty, separated from her husband, friend of Chad’s |

| Jeanne de Vionnet | her attractive young daughter |

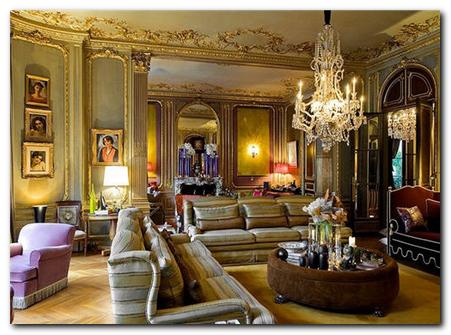

Paris interior – La belle epoque

The Ambassadors – plot summary

Lambert Strether is a middle-aged American widower who is engaged to be married to Mrs Newsome, the widow of a wealthy manufacturer. She dispatches him on an errand to bring back her son Chadwick (Chad) who is living in Paris, so that he can take his place at the head of the family business. She also fears that he has fallen under someone’s bad influence, presumably a woman.

Strether makes the journey, and on the way meets Miss Goostrey, a spirited American woman who has lived in Paris for years and offers to act as his ‘guide to Europe’. He discovers that Chad has improved and become more confident and sophisticated during his stay in Paris. This seems to be largely due to his relationship with Madame de Vionnet, a glamorous countess who is separated from her husband and who has an equally attractive daughter. Strether is not sure with which of the two women Chad is contemplating a relationship, but he too is attracted to them, and he also falls under the positive influence of the capital city and its pleasures.

Strether makes the journey, and on the way meets Miss Goostrey, a spirited American woman who has lived in Paris for years and offers to act as his ‘guide to Europe’. He discovers that Chad has improved and become more confident and sophisticated during his stay in Paris. This seems to be largely due to his relationship with Madame de Vionnet, a glamorous countess who is separated from her husband and who has an equally attractive daughter. Strether is not sure with which of the two women Chad is contemplating a relationship, but he too is attracted to them, and he also falls under the positive influence of the capital city and its pleasures.

When Strether fails to send Chad back to America and decides not to return there himself, a second rescue party is sent out to effect the diplomatic mission. This comprises Sarah, Chad’s sister, her husband Jim Pocock, and Mamie, Jim’s younger sister. The principal characters spend a great deal of time speculating about which of them is having the greater degree of influence on the others, but eventually Chad’s sister reveals that both she and her mother think Madame de Vionnet is a disgraceful woman. Mrs Newsome makes her displeasure felt by suspending her correspondence with Strether.

Strether thinks he has a solution to the problem, but on an outing into rural France he encounters Chad and Mdme de Vionnet in a situation that reveals their true intimacy, which other people have known about all along. Strether feels he has been used and betrayed, but nevertheless that Mdme de Vionnet’s influence on Chad has been positive. Knowing that he can no longer count on his engagement to Mrs Newsome, and turning down an offer of marriage to Maria Goostrey, he decides to go back to America, and face an uncertain future.

The novel in a nutshell

“Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to. It doesn’t so much matter what you do in particular so long as you have your life. If you haven’t had that what have you had? … I’m too old—too old at any rate for what I see… What one loses one loses; make no mistake about that. Still, we have the illusion of freedom; therefore don’t, like me to-day, be without the memory of that illusion. I was either, at the right time, too stupid or too intelligent to have it, and now I’m a case of reaction against the mistake… Do what you like so long as you don’t make it. For it was a mistake. Live, live!”

Lambert Strether to Little Bilham Book Fifth: Chapter Two

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

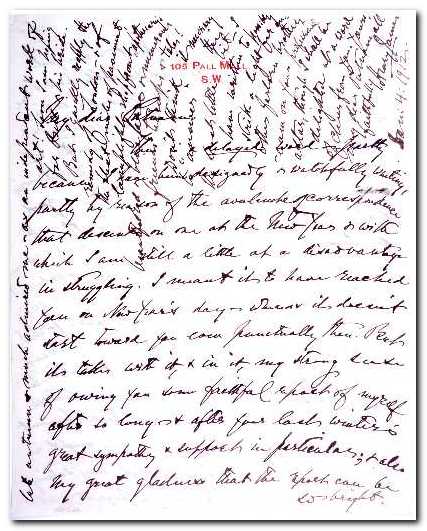

a Henry James manuscript

This is an example of what’s called ‘criss cross’ writing. To save paper, and because the postal service once charged by the sheet, many people wrote their letters in two directions on the page, perpendicularly to each other. It was not unusual to use both sides of the page, and thus get four pages of writing onto one sheet of paper.

The writing is not so difficult to read as you might imagine. We are accustomed to reading English language from left to right and from top to bottom on the page. Writing going in another direction becomes like ‘wallpaper’ in the background.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories