internationalism, pacifism, and social resistance

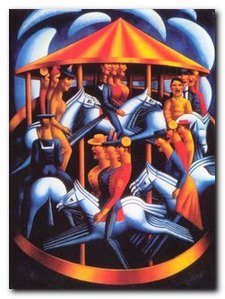

The painter Mark Gertler was a pacifist who refused to support Britain’s involvement in the First World War. After the Battle of the Somme he painted Merry-go-Round (1916). Considered by many art critics as the most important British painting of the First World War, Merry-go-Round, shows a group of military and civilian figures caught on the vicious circle of the roundabout. One gallery refused to show the painting because Gertler was a conscientious objector. Eventually it appeared in the Mansard Gallery in May, 1917.

The painter Mark Gertler was a pacifist who refused to support Britain’s involvement in the First World War. After the Battle of the Somme he painted Merry-go-Round (1916). Considered by many art critics as the most important British painting of the First World War, Merry-go-Round, shows a group of military and civilian figures caught on the vicious circle of the roundabout. One gallery refused to show the painting because Gertler was a conscientious objector. Eventually it appeared in the Mansard Gallery in May, 1917.

Society hostess Ottoline Morrell was educated at home and at Somerville College, Oxford, where she studied politics and history. Her husband Philip Morrell became a Liberal MP (for Blackburn) following the general election in 1906. He was critical of the government’s position on the First World War. They sheltered a number of conscientious objectors on their farm estate at Garsington near Oxford, including Duncan Grant, Clive Bell, and Mark Gertler. It was there that Siegfried Sassoon, recuperating after a period of sick leave, was encouraged to go absent without leave in a protest against the war.

Much scoffing has been expressed by their guests in thinly-veiled depictions in their novels about the luxury and extravagance of Garsington – but the truth is that the Morrells were sailing financially close to the edge, and eventually they had to sell the entire estate. Because Ottoline Morrell had a brief relationship with one of her members of staff, it’s assumed that this provided the creative spark for D.H.Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

The writer Gerald Brenan was unusual as a member of the Bloomsbury set, because he did serve in the war. He was the son of an army officer, and was partly educated at the military academy at Sandhurst. He served from 1914 to 1919 and was, as his biographer Jonathan Gaythorne-Hardy points out, a ‘brave, successful, conscientious and enthusiastic officer’. He spent over two years on the Western Front, reaching the rank of captain and winning a Military Cross and a Croix de Guerre.

David Bomberg – The Mudbath 1914

Biographer Lytton Strachey was a conscientious objector during the war. He is famous for his confrontation with the board which interrogated objectors. His claims of pacifism were challenged by a board member asking him what he would do if he found a German soldier raping his sister. His witty riposte was ‘I should try and come between them’. What is less well known is that Strachey could easily have evaded the inquisition on medical grounds, but didn’t. Even less well known than that is the fact that he wrote a polemical essay against the war.

The painter Duncan Grant was a pacifist, like most of the members of the Bloomsbury group, In order to be exempted from military service during World War I, he and David Garnett (his lover at the time) moved to Wissett in the Suffolk countryside to become farm labourers. Although they were at first refused exemption by a tribunal, they appealed and were eventually recognised as conscientious objectors.

Harold Nicolson worked as a diplomat in the Foreign Office. Because of this, he was exempt military service during the first world war. After the end of the first world war he took part in the Paris Peace Conference, and he was very critical of the punitive reparations extracted by the allies (which also caused his fellow Bloomsburyite John Maynard Keynes to resign from the commission).

Between the wars he flirted briefly with Sir Oswald Mosley’s fascists, but then entered the House of Commons as National Labour Party member for Leicester West in 1935. (His wife refused to visit the constituency, regarding it as ‘bedint’ – a family slang term for ‘unacceptably low class’.)

He was very active as a parliamentarian, and became a keen supporter of Winston Churchill, especially during the second world war, when he was appointed private secretary to the Minister of Information in the government of national unity. He lost his seat in the 1945 election, and then despite joining the Labour Party, he failed to get back into parliament. He is a fairly rare example of someone from the upper class whose political allegiances moved leftwards as he got older.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

John Maynard Keynes lectured in economics at Cambridge on and off from 1908. He also worked at the India Office and in 1913 as a member of the Royal Commission on Indian finance and currency, published his first book on the subject. His expertise was in demand during the First World War. He worked for the Adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer and to the Treasury on Financial and Economic Questions. Among his responsibilities were the design of terms of credit between Britain and its continental allies during the war, and the acquisition of scarce currencies.

He represented the Treasury at the Versailles Peace Conference, but resigned in strong opposition to the terms of the draft treaty which he set out in his next book Economic Consequences of the Peace, (1919). Keynes argued that the war reparations imposed on Germany could not be paid by a country which had been devastated by war. He warned that this would lead to further conflict in Europe – which of course turned out to be true.

The poet Rupert Brooke is often (quite erroneously) classed as a ‘war poet’ because some of his early works glamourised the idea of war – and he was in fact a fervent supporter of it. But he never saw active service. His poetry gained many enthusiasts and he was taken up by Edward Marsh, who brought him to the attention of Winston Churchill, who was at that time First Lord of the Admiralty. Through these connections he was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a temporary Sub-Lieutenant shortly after his 27th birthday and took part in the Royal Naval Division’s Antwerp expedition in October 1914.

He sailed with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on 28 February 1915 but developed sepsis from an infected mosquito bite. He died on 23 April 1915 off the island of Lemnos in the Aegean on his way to a battle at Gallipoli. As the expeditionary force had orders to depart immediately, he was buried in an olive grove on the island of Skyros, Greece.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War — Part I

The Bloomsbury Group and War — Part I

© Roy Johnson 2004

Bloomsbury Recalled is written by Quentin Bell, one of the last surviving members of the Bloomsbury circle. He offers a disarmingly candid portraits of his father, Clive Bell, who married the author’s mother, Vanessa Stephen (Virginia Woolf’s sister). He pursued love affairs while Vanessa, after a clandestine affair with art critic Roger Fry, lived openly with bisexual painter Duncan Grant, with whom she had a daughter, Angelica. Clive, Duncan and Vanessa were reunited under one roof in 1939, and the author conveys a sense of the emotional strain of growing up in ‘a multi-parent family.’ Acclaimed biographer of his aunt, Virginia Woolf, Bell here defends her as a feminist and pacifist. Along with chapters on John Maynard Keynes, Ottoline Morrell and art historian-spy Anthony Blunt, there are glimpses of Lytton Strachey, novelist David Garnett (Angelica’s husband) and Dame Ethel Smyth, the pipe-smoking lesbian composer, who fell in love with Virginia Woolf.

Bloomsbury Recalled is written by Quentin Bell, one of the last surviving members of the Bloomsbury circle. He offers a disarmingly candid portraits of his father, Clive Bell, who married the author’s mother, Vanessa Stephen (Virginia Woolf’s sister). He pursued love affairs while Vanessa, after a clandestine affair with art critic Roger Fry, lived openly with bisexual painter Duncan Grant, with whom she had a daughter, Angelica. Clive, Duncan and Vanessa were reunited under one roof in 1939, and the author conveys a sense of the emotional strain of growing up in ‘a multi-parent family.’ Acclaimed biographer of his aunt, Virginia Woolf, Bell here defends her as a feminist and pacifist. Along with chapters on John Maynard Keynes, Ottoline Morrell and art historian-spy Anthony Blunt, there are glimpses of Lytton Strachey, novelist David Garnett (Angelica’s husband) and Dame Ethel Smyth, the pipe-smoking lesbian composer, who fell in love with Virginia Woolf.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

Hello, I’ve read your essay in some parts, its very interesting. Can you please tell me how they escaped going to war (the young men in the group)

Thank you.

They registered as ‘conscientious objectors’. This was a legal opportunity to opt out of combat if you could convince a panel (of sceptical and generally hostile) experts, that you had moral or religious convictions which prevented you from taking up arms. Most of the Bloomsbury figures managed to escape service in that way. Some of them were forced to do other work instead – such a labouring on farms.