tutorial, commentary, web links, and study resources

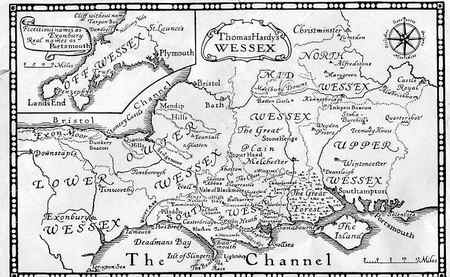

The Return of the Native first appeared as a serial in Belgravia magazine between January and December 1878. This was a publication which specialised in sensation fiction. It was then published in the popular three-volume novel format later the same year by Smith, Elder. Hardy made extensive revisions to the text when it was reprinted as part of the first collected edition of his works in 1895 and later for Macmillan’s Wessex Edition in 1912. These revisions however do not affect the substance of the plot: they were mainly to do with substantiating the geography of the story and drawing the fictitious place names more closely in line with the topography of Dorsetshire which Hardy had re-imagined as Wessex.

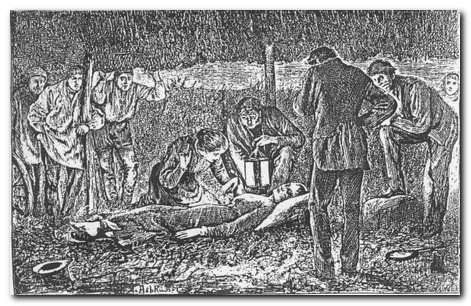

‘Something was wrong with her foot’

original illustration by Arthur Hopkins

The Return of the Native – critical commentary

Setting

One of the features that concentrates the novel and its drama is that every single scene is set in Egdon Heath and its immediate surroundings. The heath is shown in all seasons, and its vegetation and wild life is documented with almost scientific accuracy.

It is interesting to note that for those who wish to escape rural isolation, Budmouth is the nearest urban centre. Eustacia has come from there, and it is the town with its ‘promenades and parades’ to which she wishes to escape in the novel’s finale.

Hardy makes no attempt to glamourise the countryside: it is harsh terrain; people get soaking wet when it rains; and even those who make their living from it have to wear protective clothing to guard against the furze.

Melodrama

It was very common in the nineteenth century for novels to have complex plots and lots of dramatic tension. Novels first appeared in serialized form, and performed a similar function to television soap operas today. Even though Hardy is now seen as a bridge between these conventions and those of the modern era, he was repeatedly drawn to arrange his stories in a way in which drama tips over into melodrama. A central scene from the novel illustrates this point very well: the episode in which Mrs Yeobright is refused entry to Clym’s house.

She has decided to seek reconciliation with her estranged son, but when she arrives at the house Clym is asleep, and Eustacia is entertaining her ex-lover Wildeve. Hardy devises clever plotting in order to make these circumstances and coincidences to seem plausible to the reader. But when Mrs Yeobright turns to go back home, full of anger and resentment at being refused admission, it is tipping over into melodrama to have her then bitten by a snake. Though it has to be said that Hardy had flagged up their presence on the Heath earlier in the novel.

Sexual liberties

It is also interesting to note how often in his fiction Hardy explores the boundaries of sexual liberty. At a time when both men but particularly women were supposed to remain chaste until marriage, Hardy is adept at exploiting circumstances in which these restraints could be circumvented or challenged.

In a scene which takes place outside the time frame of the narrative, Thomasin Yeobright and Damon Wildeve have travelled to Southerton in order to be married. The marriage does not take place because the paperwork was made out for Budworth.

The importance of this detail is that they have stayed somewhere away from home, as a couple, without being married. It is not clear if sexual intimacy took place or not, but the mere possibility that it could have done puts a stain on Thomasin’s character, for which her aunt reproaches her: “It is a great slight to me and my family and when it gets known there will be a very unpleasant time for us”.

A very similar set of circumstances obtain in Hardy’s earlier novel of 1872, A Pair of Blue Eyes in which the protagonists Stephen Smith and Elfride Swancourt have a failed elopement to Plymouth (then London) which results in their being absent from their home town for one night together (which they spend travelling on trains) – but this is enough to put her social reputation entirely at risk.

The Return of the Native – study resources

![]() The Return of the Native – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Return of the Native – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Return of the Native – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Return of the Native – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Return of the Native – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Return of the Native – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Return of the Native – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Return of the Native – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Return of the Native – York Notes (Advanced) – Amazon UK

The Return of the Native – York Notes (Advanced) – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

![]() The Return of the Native – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

The Return of the Native – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Return of the Native – audiobook version at LibriVox.org

The Return of the Native – audiobook version at LibriVox.org

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

The Return of the Native – characters

| Diggory Venn | young handsome man (24) covered in red dye for most of the novel, and a persistent peeping tom and eavesdropper |

| Grandfer Cantle | a yokel who reminisces about his role in Napoleonic wars |

| Chistian Cantle | a young unmarried man (31) who is a self-elected loser |

| Mrs Yeobright | a proud and strict woman, the daughter of a curate |

| Clement (Clym) Yeobright | her son, ex-jewellery salesman, would-be schoolmaster |

| Thomasin (Tamsin) Yeobright | Mrs Yeobright’s niece |

| Damon Wildeve | an inn-keeper and former engineer |

| Eustacia Vye | a passionate and romantic woman, Wildeve’s former lover |

| Susan Nonsuch | a country woman |

| Johnny Nonsuch | her son, young boy who carries messages |

| Captain Drew | a retired seaman, Eustacia’s grandfather |

| Olly Dowden | a country woman, maker of brooms |

| Timothy Fairway | a rural worker |

The Return of the Native – plot summary

Book the First – The Three Women

November bonfire celebrations are taking place on Egdon Heath. A group of locals decide to celebrate the nuptials of Thomasin Yeobright and Damon Wildeve, but it turns out that they were not married because of irregularities in the marriage licence. Damon goes to meet Eustacia Vye, his former lover, who has been waiting for him on the Heath. She charges him to remain faithful to her.

Their conversation is overhead and transmitted to Diggory Venn, who has been turned down as a suitor to Thomasin, but has remained faithful in his love for her. He spies on Damon and Eustacia, who cannot resolve their feelings for each other. Venn then asks Eustacia to leave Damon for Tamsin, which she refuses to do. Mrs Yeobright intervenes to protect her niece’s good name by telling Wildeve that Tamsin has another suitor (Venn). Damon and Eustacia continue to equivocate.

Book the Second – The Arrival

Eustacia hears her name linked with the absent Clym Yeobright, and becomes fired up romantically by his reputation alone. Tamsin continues to worry about her local reputation since she and Wildeve are still not married. Eustacia tries to meet Clym on his return to Egdon Heath, but fails in her attempt.

She arranges to take part in the Christmas mummers play, where she meets Clym, falls further in love with the mere idea of him, and becomes jealous of Tamsin. She breaks off her relationship with Wildeve, who goes back to Tamsin again and is accepted by him. Tamsin finally marries Wildeve, and is given away by Eustacia (all of which is arranged by Diggory Venn).

Book the Third – The Fascination

Clym has returned from being a jewellery shop salesman in Paris with the intention of setting up a school, despite his mother’s disapproval. He recruits Eustacia to his scheme, and his mother criticises both his lack of ambition and his connection with a flirt who has no money.

Clym falls for Eustacia and decides he wants to marry her, but she thinks that their love might not last. Eventually they agree to marry in fourteen day’s time. Clym leaves home and sets up a small rented house on the Heath. His mother is full of bitter disappointment. She sends inherited money to Tamsin but Christian loses it all gambling against Wildeve, who then loses it all in his turn to Diggory Venn, who gives it all back to Tamsin (though half was intended for Clym).

Book the Fourth – The Closed Door

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

When he is struck with an eye ailment through reading too much, he decides to become a humble furze-cutter. Eustacia goes to a rural dance and meets Wildeve again – and is observed by Diggory Venn once more, who then begins an active campaign to distract Wildeve’s attentions towards Eustacia (all in order to protect Tamsin).

Venn encourages Mrs Yeobright to reconcile herself with Clym, and Clym feels he ought to do the same. Mrs Yeobright finally goes to Clym’s house, but arrives when he is asleep and Eustacia is being visited by Wildeve. Mrs Yeobright finds the door closed against her, and is mortified. When Clym wakes up he goes in pursuit of his mother and finds her collapsed on the Heath, having been bitten by an adder. Eustacia follows, meets Wildeve en route to discover that he has inherited eleven thousand pounds, and arrives at the Heath as Mrs Yeobright is dying from exhaustion, snake bite, and a broken heart.

Book the Fifth – The Discovery

Clym falls ill after his mother’s death and reproaches himself for not having made contact with her.Then he learns from Diggory Venn and young Johnny the true sequence of events that led to his mother’s failed visit. He confronts Eustacia, who admits to all except Wildeve’s identity as the person who was in the house with her. Clym is convinced that she is having an affair with someone, they argue, and eventually agree to separate. Eustacia goes back to live at her grandfather’s house and momentarily contemplates suicide.

Eustacia then plans to leave for Paris via Budworth, with Wildeve’s financial assistance. Clym writes to Eustacia inviting her back, and Tamsin has differences with Wildeve regarding Eustacia. Failing to receive Clym’s letter, Eustacia sets off to meet Wildeve and is caught in a storm on Egdon Heath. Susan Nonsuch curses Eustacia with a wax effigy. Tamsin seeks Clym’s help, and despatches him to check on Eustacia and Wildeve, who appear to be eloping. Eventually, Clym and Wildeve meet on the Heath. Eustacia falls into a weir, both men try to save her, but Eustacia and Wildeve are drowned.

Book the Sixth – Aftercourses.

Diggory Venn becomes a prosperous dairy farmer. Clym thinks to take up with Tamsin (as his mother once wished) but she marries Diggory Venn instead. Clym becomes an itinerant preacher, still devoted to the memory of his mother.

The Return of the Native – bibliography

Gillian Beer, ‘Can the Native Return?’ in her Open Fields: Essays in Cultural Encounter (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 31-54.

Kristin Brady, ‘Thomas Hardy and Matters of Gender’, in Dale Kramer (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 93-111.

Pamela Dalziel, ‘Anxieties of Presentation: The Serial Illustrations to Hardy’s The Return of the Native‘, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 51.1 (1996), 84-110.

Terry Eagleton, ‘Nature as Language in Thomas Hardy’, Critical Quarterly, 13 (1971), 155-172.

Joseph Garver, The Return of the Native, Penguin Critical Studies, (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1988).

Jennifer Gribble, ‘The Quiet Women of Egdon Heath’, Essays in Criticism, 46.3 (1996), 234-257.

Nicola Harris, ‘”The Danse Macabre”, Hardy’s The Return of the Native, Browning, Ruskin and the Grotesque’, Thomas Hardy Yearbook, 26 (1998), 24-30.

Robert Langbaum, Thomas Hardy in Our Time, (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1995).

Phillip Mallet, ‘Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native‘, in Jay Parini (ed. and introd.), British Writers: Classics, vol. i (New York: Scribner’s, 2003), 291-310.

Mary Rimmer,’A Feast of Language: Hardy’s Allusions’, in Phillip Mallet (ed.), The Achievement of Thomas Hardy (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000), 58-71.

Dennis Taylor, ‘Hardy Inscribed’, in Phillip Mallet (ed.), The Achievement of Thomas Hardy (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000), 104-122.

Brian Thomas, The ‘Return of the Native’: Saint George Defeated (New York: Twayne, 1995).

Hardy’s WESSEX

The Return of the Native – further reading

![]() John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

![]() Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

![]() L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

![]() Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

![]() R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

![]() Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

![]() James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

![]() Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

![]() P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

![]() P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

![]() Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

![]() R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

![]() Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

![]() F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

![]() Norman Page, Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

Norman Page, Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

![]() Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

![]() Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

![]() Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

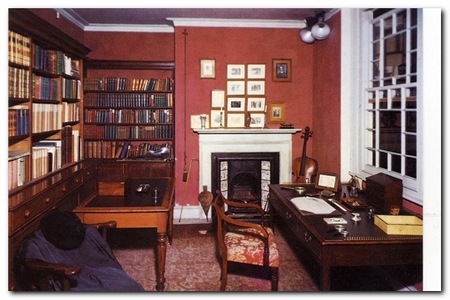

Hardy’s study

reconstructed in Dorchester museum

Other works by Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Thomas Hardy – web links

Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, book reviews. bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

The Thomas Hardy Collection

The complete novels, stories, and poetry – Kindle eBook single file download for £1.29 at Amazon.

Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, the novels and literary themes, poetry, religious beliefs and influence, biographies and criticism.

The Thomas Hardy Society

Dorset-based site featuring educational activities, a biennial conference, a journal (three times a year) with links to the texts of all the major works.

The Thomas Hardy Association

American-based site with photos and academic resources. Be prepared to search and drill down to reach the more useful materials.

Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production features, box office, film reviews, and even quizzes.

Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Small collection of academic papers and articles ‘favoring signed articles by recognized scholars and articles published in peer-reviewed sources’.

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Evolution of Wessex, contemporary reviews, maps, bibliography, links to other web sites, and history.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Thomas Hardy

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories