tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Solution first appeared in the monthly magazine The New Review in three issues between December 1889 and February 1990. It was specially commissioned for the new publication, which was founded and edited by Archibald Grove. The story itself was based on an anecdote related to James by his friend the actress Fanny Kemble.

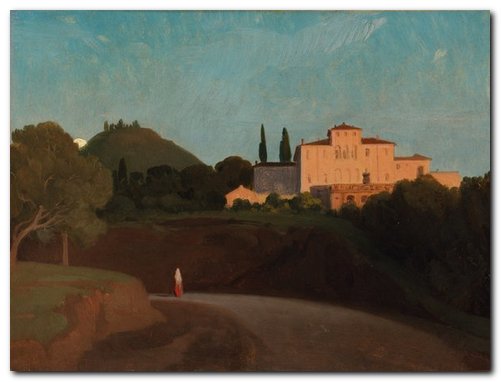

Frascati – Paul Flandrin

The Solution – critical commentary

Social conventions

Contemporary readers might find it difficult to appreciate the social nicety which is at the crux of this tale. During a group excursion to a picnic, Wilmerding quite innocently goes for a walk with Veronica, the eldest daughter of Mrs Goldie. They are missing from the main group for some time.

In the nineteenth century (and earlier) the social conventions for contact between men and women were so tightly controlled that for a single woman to be alone with a single man – out of any supervision by a chaperone, a family friend, or any other third party – was considered to be a potential blot upon her reputation.

The inference is clearly a prurient fear of some sexual connection being made, but alongside or even beneath that in the case of the class James was writing about is a financial fear that social capital would be lost. The woman’s reputation could not be converted into real capital via marriage arranged on

Mrs Goldie’s social ambition is to find husbands for her daughters. This is not an easy task, because she herself has no money (compared with people in the circles where she is mixing) and two of her daughters are not attractive.

Veronica alone has the social capital of good looks; but if her reputation were to be sullied by what was considered an episode of improper behaviour, that capital would be lost. This is a situation he had already explored in his famous novella Daisy Miller more than ten years previously.

This is the crux of the trick played on Wilmerding by Montaut and the narrator: they know that he has such an elevated sense of honour that he will be prepared to marry Veronica if he thinks he has placed her in an untenable position.

The international dimension

Wilmerding is an upright and naive American who has found himself out of his depth amidst European social mores. From his republican background, he doesn’t realise the significance of taking an innocent stroll with a young unmarried woman.

The two Europeans, the narrator and Montaut, realise that Wilmerding has unwittingly placed himself in a socially embarrassing position, and they play on his credulity and his sense of honour – the Frenchman Montaut more unscrupulously than the English narrator. .

Fear of marriage

It is difficult not to see this as yet another variation on the theme of ‘fear of marriage’ which James explored in so many of his stories. We know that James debated with himself the tension between marriage and remaining a bachelor – always coming down on the side of the latter. And this is not even taking into account the homo-erotic impulses to which he eventually gave way later in life.

The story illustrates the danger posed by a pretty face and an unmarried woman. One innocent stroll in the Italian countryside is enough for a man of honour to be entrapped – obliged to proffer marriage when no such gesture was contemplated or intended.

Of course this instance is slightly amusing, because Wilmerding is rescued from his trapped condition by the whiles of a clever woman, Mrs Rushbrook, who simultaneously ‘bags her man’. Nevertheless, he has to pay a price, which Mrs Goldie is happy to seize on.

If you wished to push the ‘fear of women and marriage’ argument even further, you could argue that Mrs Rushbrook not only ‘snares’ Wilmerding, but also relieves him of his money in doing so. So – two women strip him of his independence and his money. Bachelors beware!

The framed narrative

James was very fond of the framed narrative – where there is an account of how the story comes about enclosing another more detailed narrative of the story itself. But the ‘frame’ here is not complete. The inner narrator (the un-named diplomat) is already dead when the story begins, and the main narrative is the outer-narrator’s reconstruction of events with ‘amplification’.

It is rather curious that James should take the trouble to create this double sourcing of the narrative when he makes no further use of it after the introductory paragraph. But it is entirely in keeping with his manner of creating stories, as the even more complex example of The Turn of the Screw proves.

The Problem – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Solution – HTML version at The Ladder

The Solution – HTML version at The Ladder

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Solution – plot summary

Part I. An un-named narrator, a former officer from the English diplomatic service, looks back to his posting in Rome in the early part of the nineteenth century when he was twenty-three. He mixes with attachés Wilmerding and Montaut from the United States and French embassies respectively in a social life which centres on an English widow Mrs Blanche Goldie and her three daughters.

They visit Mrs Goldie at an afternoon tea-party near Frascati, Wilmerding is missing for some time with Veronica, the most attractive of Mrs Goldie’s daughters. Montant argues to the narrator that this indiscretion obliges Wilmerding to make an offer of marriage to Veronica, otherwise her reputation will be compromised. They disagree, and make a bet on the outcome.

Part II. After the holiday the diplomats reassemble in Rome. The narrator teases Wilmerding for having returned without having made any formal commitment to Veronica. They discuss the subtle differences between American and European conventions regarding single men and women. As something of a joke, the narrator claims that Wilmerding has ‘gone too far’ with Veronica, at which Wilmerding professes complete innocence regarding his intentions.

Wilmerding consults Montant for advice – then suddenly leaves to go back to Frascati. Montant then claims he has won the bet – because Wilmerding will feel obliged to marry Veronica out of a sense of honour. But the narrator rides after Wilmerding, arriving back at Frascati to find that Wilmerding is already engaged to Veronica – so he rides on to seek advice from Mrs Rushbrook, the widow of an English naval officer who he wishes to marry.

Part III. The narrator feels very remorseful that his ‘joke’ has backfired and implores Mrs Rushbrook to help him quash the engagement. She argues that his best recourse would be to offer to marry Veronica himself. The next day the narrator goes to see Mrs Goldie to explain the misunderstanding. She refutes his arguments on the grounds that nobody knows what Wilmerding’s motives are.

She also challenges the narrator to propose marriage himself to Veronica – since although he has no money, he is very well connected and is expected to rise in the diplomatic service. Immediately afterwards, the narrator meets Wilmerding, Veronica, and Mrs Rushbrook, who are all very friendly. Mrs Rushbrook asks for details of Wilmerding’s social background.

Part IV. Back on duty in Rome, the narrator feels embarrassed and avoids Wilmerding. He visits Mrs Rushbrook, who has done nothing to help his secret plan, and thinks Veronica will blossom once she is married. But Wilmerding suddenly leaves Rome, having been rejected by Veronica. Next day the narrator confronts Mrs Rushbrook, who says she has offered her own money to the Goldies to buy off Wilmerding. Mrs Goldie, having come into money, goes off on a world tour. The narrator then reveals that Mrs Rushbrook in fact persuaded Veronica not to marry Wilmerding in exchange for his money – and that she had married him herself.

Principal characters

| I | the un-named outer narrator who relays the tale |

| — | an un-named inner narrator – a former member of the English diplomatic service |

| Mrs Blanche Goldie | a flamboyant English widow with three unmarried daughters |

| Veronica Goldie | the most attractive daughter |

| Rosina Goldie | unattractive |

| Augusta Goldie | unattractive |

| The General | American foreign officer in Rome – a Carolinian dandy |

| Henry Wilmerding | his secretary, a rich Quaker gentleman |

| Guy de Montaut | French attaché in Rome |

| Mrs Rushbrook | an accomplished English widow of a naval officer |

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories