tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

Under Western Eyes (1911) is one of the most political of all Conrad’s novels – even though a good deal of it takes place in drawing rooms in Geneva. It is simultaneously a critique of Russian absolutism and of its reactive counterpart, revolutionary terrorism. Conrad is essentially a political conservative, but his background as a Polish national, raised under Tsarist rule, with an international career as a seaman before adopting British nationality, gives him a healthy non-partisan view on the political systems he considers.

Joseph Conrad

Conrad is now well ensconced in the Pantheon of great modernists, and his novels Lord Jim and The Secret Agent are popular classics, along with impressive novellas such as The Secret Sharer and Heart of Darkness which are even more celebrated in terms of the number of critical words written about them.

Under Western Eyes – critical commentary

Under Western Eyes, as its title suggests, is very much a depiction of Russia from the point of view of western liberal democracy. The narrator is an Englishman who was raised in Russia (‘a teacher of languages’) who reminds readers at regular intervals that many of the surprising details of the plot are products of a Slavic regime that will seem irrational to Europeans.

There is plenty of scope within the novel for Conrad to vent his antipathy to a regime that put his own father in jail and the entire Conrad family into a form of internal exile. But he does so in an even-handed sense. The government is shown as absolutist, despotic, riddled with police spies, and completely neglectful of its citizens, the majority of whom live in a state of abject squalor. But he is equally critical of the revolutionaries, who he depicts as a collection of misguided, self-serving bigots at best, and at worst as psychopaths, unprincipled anarchists, phony feminists, and murderous brutes.

It’s a triumph of Conrad’s skill that Haldin, a politically motivated revolutionary who assassinates not only a government official but several innocent bystanders, emerges as the novel progresses as an almost Christ-like figure. Similarly, the central figure Razumov, whose only clear behaviour for the majority of the novel is to betray a colleague to certain death and then act as a police informer, in the end undergoes a convincing transformation motivated by a sort of spiritual remorse.

Irony

Joseph Conrad is a master of sustained dramatic irony. It’s easy enough for any skilled writer to drop ironic statements into a narrative, but to maintain an ambiguous attitude to a subject or character throughout an entire narrative requires a very skillful form of deception. It can only be done by creating a narrative that reveals (or appears to reveal) one thing whilst other elements reveal something else. (Vladimir Nabokov is another writer who uses this technique.)

His central character Fazumov is a student of philosophy who thinks he is perceptive and clever. The other characters in the narrative reinforce this idea because they mistake his taciturn nature for ratiocinative profundity. They have confidence in him partly because of his good looks and because they assume he is acting on some high moral principle. But in fact for most of the narrative he is a mediocrity, an empty shell, and a coward.

Much of the tension in the plot is generated by the sustained dramatic irony of Razumov’s position in relation to the people he confronts. The revolutionaries mistakenly believe he has been part of the terrorist plot and in league with Haldin, its true perpetrator. He is forced to dissemble so as to conceal the fact that he in fact betrayed Haldin to the police. He is also forced to conceal from them (though this is an easier task) that he has become a police spy, tasked with reporting on terrorist plots back to the government in Russia.

Victor Haldin’s sister Natalia has learned in a letter from her brother that Razumov is a friend who can be trusted. She has every reason to believe that the two young men were friends and she hopes that Razumov can throw some light on her brother’s last hours before being arrested. Razumov is squirming with anguish in every conversation he has with her, his voice reduced to a low rasping noise as he is forced to conceal the fact that he betrayed Haldin and brought about his death. The entire novel is heavily indebted to Dostoyevski, and to Crime and Punishment in particular. Razumov like Raskolnikov spends much of his time in discussion with the police and the revolutionaries, always on the verge of confessing or giving himself away.

Narrative

As usual in his work written in his late period, Conrad adopts a complex and very oblique manner in delivering his story. His outer narrator (an English ‘teacher of languages’) recounts events he has learned from reading a journal written by the central character Razumov, some of it composed in retrospect and some contemporaneously (‘with dates’). But as in his other late novels such as Nostromo and Chance, Conrad from time to time appears to forget the narrative structure he has created for himself, and he lapses into a traditional third person omniscient narrative mode.

He recounts the thoughts, feelings, and inner motivations of minor characters – psychological motivations which could not be known to anybody else. These are figures who the narrator could only know about from having read of them as characters in Razumov’s journal, and whose inner life would therefore be hidden, certainly from a limited character such as Razumov and doubly so from another person reading about them in his reminiscences.

These flaws are not so severe that they destroy one’s faith in the novel as a whole, but they do undermine our confidence in a narrator who makes so many claims of moral discrimination – most of them on Conrad’s own behalf – despite his efforts to distance himself from the teacher of languages. They make us wonder why Conrad devises such a complex strategies when he both contravenes their logic and fails to keep accurate control of them.

The first part of the novel is relayed to us in first person narrative mode by the teacher of languages. He is reconstructing the story from a journal (‘a journal, a diary, yet not that exactly in its actual form’) kept by Razumov, that has come into his possession after the events of the novel have finished. This does not stop Conrad from drifting into third person omniscient narrative mode, speculating about issues that it is very unlikely anyone would record in a diary.

In the second part of the novel the teacher of languages talks to Haldin’s sister Natalia, who recounts her meeting with Razumov. But the events are once more delivered in third person omniscient mode:

The dame de compagnie, listening where now two voices were alternating with some animation, made no answer for a time. When the sounds of the discussion had sunk into an almost inaudible murmur, she turned to Miss Haldin.

This sort of focalisation is simply not consistent with a narrative which is supposed to originate with Miss Haldin and is being passed on to us by the teacher of languages. There are many such instances throughout the novel. Conrad also makes comments on events which are illogical or asynchronous. The teacher of languages, speaking of Haldin, observes: ‘I did not wish indeed to judge him, but the very fact that he did not escape … spoke to me in his favour’.

But he already knows why Haldin did not escape. In fact he knows the entire story before he delivers it as the novel readers hold in their hands. There are also instances where the teacher of languages invents scenes he has not witnessed and nobody has described to him. In the middle of recounting the story relayed to him by Miss Haldin, he speculates ‘I could depict to myself Peter Ivanovitch rushing busily out of the house again, bare-headed, perhaps, and on across the terrace with his swinging gait, the black skirts of the frock-coat floating clear of his stout, light-grey legs.’

For long stretches of the narrative Conrad has to pretend that the teacher of languages is unaware of the dramatic irony of presenting Razumov as a ‘friend’ of Haldin – when in fact at the very moment of starting the tale he has all the facts at his disposal. But because he takes part in the events as a fictional character, large sections of the book are related from his point of view as a spectator at the time of the events being described. This form of narration is an illusion, a conjuring trick on the author’s part. But it must be said that Conrad fails to keep the balls in the air some of the time. It’s difficult to escape the impression that Conrad was simply not paying sufficient attention to his work, although similar problems occur in other of his late novels.

Genesis of the text

These issues are further complicated by the very complex manner of Conrad’s process of composition. He wrote the novel over a two year period, breaking off at one point to produce his novella The Secret Sharer (which also deals with a character who shelters a murderer). Under Western Eyes was composed in longhand to produce a first draft, and these pages were then typed up to produce a version that Conrad corrected by hand. The result was then in turn typed into what approximated to a finished version. One problem is that all three of these stages were taking place at the same time, and another is that even when the process was complete Conrad made huge cuts and changes to the story for its publication both in serial and then in single volume form. On top of that there were also English and American editions of the novel that contain differences.

The best available version of the text is in Oxford Classics, which is based on the first English edition. But there are lots of problems in the text which need copious footnotes and extracts from other versions to explain. At one point Conrad even gets the full name of one of his important characters wrong.

Dostoyevski

Joseph Conrad claimed that he did not like the work of Fyodor Dostoyevski – an opinion perhaps fuelled by his anti-Russian feelings in general, having been exiled from his Russian-controlled Poland with the rest of his family early in life. But the parallels with Dostoyevski’s Crime and Punishment (1866) are unmistakable.

Both the protagonists – Razumov and Raskalnikov – are students. They both commit crimes and are subsequently haunted by a fear of being found out, whilst at the same time they both feel a passionate need to confess. Both men contemplate suicide as a relief from their anguish. Both these protagonists confess to a woman they love, and in a sense both are ultimately redeemed by this love.

Under Western Eyes – study resources

![]() Under Western Eyes – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon UK

Under Western Eyes – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Under Western Eyes – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon US

Under Western Eyes – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon US

![]() Under Western Eyes – annotated Kindle eBook edition

Under Western Eyes – annotated Kindle eBook edition

![]() Under Western Eyes – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

Under Western Eyes – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() Under Western Eyes – PDF version at RIA Press

Under Western Eyes – PDF version at RIA Press

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Joseph Conrad at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Under Western Eyes – plot summary

The protagonist is a young Russian student of philosophy named Razumov, a conservative and career-motivated young man. He has never known his parents, but he is in fact the natural son of Prince K—, who pays for his education. One day he returns home to find a student acquaintance named Victor Haldin sheltering in his apartment. Haldin informs Razumov that he has just committed a political assassination. He has evaded the police and intends to escape. This news causes Razumov a great deal of unease, as he has no sympathy for Haldin’s actions and feels that he is in danger of being implicated in the crime. .

Haldin asks Razumov to contact a cab driver called Ziemanitch, who may be able to help Haldin escape successfully. Razumov fears that all he has worked for is slipping away, but after much soul-searching agrees to help Haldin – primarily with the intention of getting him out of his apartment as soon as possible. When Razumov finds Ziemanitch in a drunken stupor and unable to assist, he beats him unmercifully. Then, in a state of heightened outrage at being placed in such a difficult position, he decides to betray Haldin to the police.

Haldin asks Razumov to contact a cab driver called Ziemanitch, who may be able to help Haldin escape successfully. Razumov fears that all he has worked for is slipping away, but after much soul-searching agrees to help Haldin – primarily with the intention of getting him out of his apartment as soon as possible. When Razumov finds Ziemanitch in a drunken stupor and unable to assist, he beats him unmercifully. Then, in a state of heightened outrage at being placed in such a difficult position, he decides to betray Haldin to the police.

Razumov goes to the one person that may be able to assist him – the official who arranges his sponsorship at the university. They go to the chief of police, General T – who agrees to keep Razumov’s name out of any official reports, because of his connection with Prince K—. Haldin is arrested, tried, and hanged. Razumov finds himself taking the first step to becoming a secret agent, although at this time he has no such intention.

The narrative then shifts to Geneva where Natalia and Mrs Haldin, the sister and mother of the executed revolutionary, have received the tragic news. In his last correspondence to his sister, Victor Haldin mentioned a certain serious young man named Razumov who was kind to him. Nathalie learns that Razumov is scheduled to arrive in Switzerland, and she impatiently awaits the arrival of her late brother’s final friend, hoping he might be able to shed light on Haldin’s last days.

In Geneva Razumov joins a group of exiled Russian revolutionaries who are planning an insurgency in the Baltic regions in an attempt to foment revolution in Russia. They regard Razumov as a hero, because they mistakenly think he was an associate of Haldin’s in the assassination plot. In fact he has gone to Geneva working as a spy for the Russian government.

All the publicly available evidence suggests that Razumov’s part in the arrest of Haldin can not become known. This is reinforced when news arrives that Ziemanitch has committed suicide. It is generally assumed that this was an act of remorse for betraying Haldin (which was not the case). But the strain of concealing his part in betraying Haldin causes Razumov a great deal of distress. This is compounded when he is forced to meet Nathalia and she asks him about the exact nature of his last contact with her brother.

This process of being interrogated is repeated with the key figures amongst the revolutionaries. At each stage Razumov is put under greater and greater psychological pressure and he feels more role strain and conflict of interests. He is being praised for a revolutionary act of terrorism that he did not commit, and his true political beliefs are deeply conservative.

However, powerfully affected by Natalia’s beauty and trustful nature, he finally breaks down and confesses to her. He then does the same thing with the revolutionaries, who punish him by bursting his ear drums. As a result of his deafness, he is run over by a street car and rendered a cripple. At the end of the novel, after her mother dies, Natalia goes back to Russia to do good works amongst poor people. Razumov has gone back too, but is not expected to live long.

Principal characters

| I | The un-named outer narrator, ‘a teacher of languages’, who presents events and participates in the story. |

| Kyrilo Sidorovitch Razumov | A student of philosophy |

| Prince K— | Razumov’s protector, sponsor, and secret father |

| Victor Haldin | A student and revolutionary |

| Ziemianitch | A drunken cab driver |

| General T— | Government official to whom Razumov betrays Haldin |

| Kostia | A dissolute student with a rich father |

| Gregory Matvieitch Mikulin | Police investigator |

| Natalia Haldin | Victor Haldin’s sister |

| Mrs Haldin | Victor Haldin’s mother |

| Peter Ivanovitch | A revolutionary and feminist |

| Madame de S— | Russian society revolutionary sympathiser |

| Father Zosim | Priest and police informer |

| Tekla | Servant and former revolutionary |

| Sophia Antonovna | Revolutionary |

| Nikita Necator | Revolutionary assassin – and police spy |

| Julius Caspara | Magazine editor and anarchist |

Joseph Conrad – biography

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

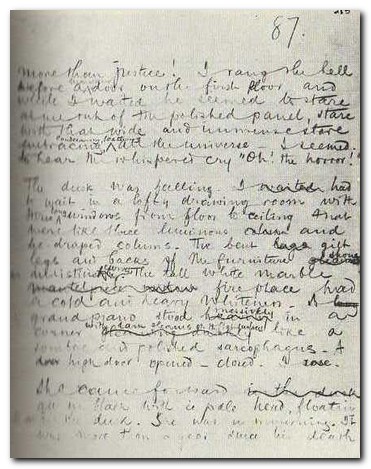

Manuscript page from Heart of Darkness

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941.

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010.

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010.

![]() Hillel M. Daleski, Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977.

Hillel M. Daleski, Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977.

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985.

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940.

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940.

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958.

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992.

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992.

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979.

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990.

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976.

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976.

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966.

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980.

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980.

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work, London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work, London: Northcote House, 1994.

Major novels by Joseph Conrad

Nostromo (1904) is Conrad’s ‘big’ political novel – into which he packs all of his major subjects and themes. It is set in the imaginary Latin-American country of Costaguana – and features a stolen hoard of silver, desperate acts of courage, characters trembling on the brink of moral panic. The political background encompasses nationalist revolution and the Imperialism of foreign intervention. Silver is the pivot of the whole story – revealing the courage of some and the corruption and destruction of others. Conrad’s narration is as usual complex and oblique. He begins half way through the events of the revolution, and proceeds by way of flashbacks and glimpses into the future.

Nostromo (1904) is Conrad’s ‘big’ political novel – into which he packs all of his major subjects and themes. It is set in the imaginary Latin-American country of Costaguana – and features a stolen hoard of silver, desperate acts of courage, characters trembling on the brink of moral panic. The political background encompasses nationalist revolution and the Imperialism of foreign intervention. Silver is the pivot of the whole story – revealing the courage of some and the corruption and destruction of others. Conrad’s narration is as usual complex and oblique. He begins half way through the events of the revolution, and proceeds by way of flashbacks and glimpses into the future.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Secret Agent (1907) is a short novel and a masterpiece of sustained irony. It is based on the real incident of a bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory in 1888 and features a cast of wonderfully grotesque characters: Verloc the lazy double agent, Inspector Heat of Scotland Yard, and the Professor – an anarchist who wanders through the novel with bombs strapped round his waist and the detonator in his hand. The English government and police are subject to sustained criticism, and the novel bristles with some wonderfully orchestrated effects of dramatic irony – all set in the murky atmosphere of Victorian London. Here Conrad prefigures all the ambiguities which surround two-faced international relations, duplicitous State realpolitik, and terrorist outrage which still beset us more than a hundred years later.

The Secret Agent (1907) is a short novel and a masterpiece of sustained irony. It is based on the real incident of a bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory in 1888 and features a cast of wonderfully grotesque characters: Verloc the lazy double agent, Inspector Heat of Scotland Yard, and the Professor – an anarchist who wanders through the novel with bombs strapped round his waist and the detonator in his hand. The English government and police are subject to sustained criticism, and the novel bristles with some wonderfully orchestrated effects of dramatic irony – all set in the murky atmosphere of Victorian London. Here Conrad prefigures all the ambiguities which surround two-faced international relations, duplicitous State realpolitik, and terrorist outrage which still beset us more than a hundred years later.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Joseph Conrad web links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

![]() Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

![]() Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

![]() Works by Joseph Conrad

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society of America

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

![]() Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales