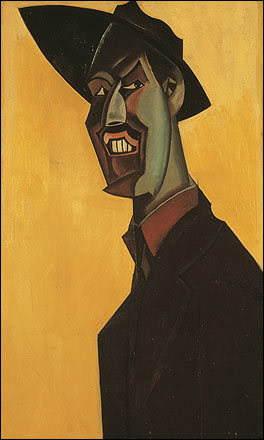

painter, novelist, critic, bohemian rebel

Wyndham Lewis was a controversial figure in English modernism between 1912 and 1954. He was both a graphic artist and a novelist, and he collaborated with some of the most influential creative figures of the period – the American poet Ezra Pound, the French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and the British painter Augustus John. He is credited as the co-inventor of Vorticism – the one native English movement in modern art.

Lewis was born in 1882 in Amhurst, Nova Scotia to an American father and an English mother. His full name included ‘Percy’, but as an adult he tried to discourage its use. In 1888 the family moved to England and his parents separated. Percy was raised by his mother in Norwood, south London, whilst his father settled in Ryde on the Isle of Wight. His father was a licentious and improvident character who lived on money supplied by an older brother.

Lewis was sent to boarding school in Bedford then to Rugby for two years where his academic record was poor. But he showed promise in painting and drawing. At sixteen he was enrolled at the Slade, where his drawing instructor was Henry Tonks, whose previous students included Augustus John.

Despite erratic attendance, Lewis did well and in 1900 won a two-year scholarship. However, he was expelled from the college after a year – for a combination of smoking and bad timekeeping. William Rothenstein introduced him to Augustus John, whom he henceforth regarded with a sort of hero-worship.

He moved into Fitzrovia, from where he made excursions to Spain and Holland, before settling in Paris. There he acquired his first mistress – a German woman Ida Vendel who was three years his senior. He now had two women who were supporting him financially – his mother and his lover.

There were plans to marry Ida, but he was subject to jealous rages when he discovered she had had lovers in her past. After a brief sojourn in Munich he returned to Paris, and although he spent most days in studios, he also had literary ambitions. There was a plan to write a series of sonnets. He spent a summer and Xmas holiday in the company of Augustus John and his family, but continued to cadge money from Ida and his mother, who even repaid his debts to other people.

Depressed by the failure of his relationship to Ida, he relapsed into a state of neurasthenia, which was then the fashionable term for unspecified maladies. To add to his woes he managed to contract gonorrhoea on a visit to Spain. In 1909 he made his literary debut in the English Review, alongside contributors such as Roger Fry and Clive Bell. He exhibited at the Grafton Group exhibition and participated at first in the Omega Workshops enterprise. But very quickly a series of disagreements and misunderstandings arose. Lewis reacted by producing libellous round robin denouncing Fry which put an end to the association.

He branched out into similar enterprises of his own. He collaborated with Richard Nevinson on designs for futurist tableaux vivants, and together with Ezra Pound and Cuthbert Hamilton established the Rebel Arts Centre. Lewis had a new suit made to emphasise his importance of his role as the Managing Director. The enterprise came to nothing.

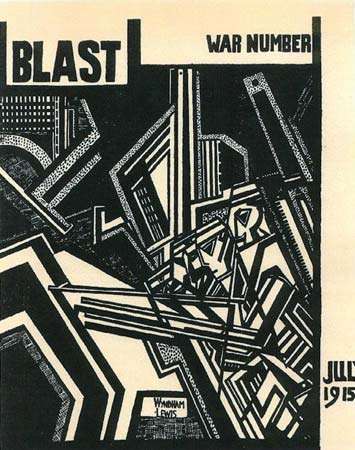

His next venture was the magazine BLAST which was launched, appropriately enough, a few days before the start of the First World War. It was virtually the journal of the English Vorticist movement, for which Lewis wrote most of its largely incoherent manifesto. The magazine caused a minor sensation, then like so many other avant-garde publications of its type, it folded after the second issue.

In his private life Lewis was breaking away from Olive Johnson, who had just borne his second child. His daughter Betty and son Peter were both raised by Lewis’s mother.

In 1916 he tried very hard to find a cushy appointment in the army, but had to settle for being a bombardier. He was posted to the front line in northern France, and whilst in the thick of heavy fighting he amazingly continued to edit the proofs of his novel Tarr which was being serialised in Harriet Weaver’s magazine The Egoist.

The following year he was given compassionate leave when his mother became dangerously ill with pneumonia. He had his leave extended thanks to the intervention of Nancy Cunard and wangled his way into becoming an official war artist. After a brief affair with Sybil Hart-Davis whose husband was fighting as a captain at the front in France he took up with Iris Barry (real name Frieda Crump) who became mother to his third child Robin. The boy was raised by his maternal grandmother and didn’t know the identity of his parents until he became an adult.

A second child Mavis was put into a ‘Home for the Infants of Gentlepeople’. Iris Barry went on to become the first film critic for the Spectator and the cinematic curator for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She is the subject of his magnificent portrait Praxitella. But Lewis left her behind in his wake as he became something of a celebrity portrait painter. He also had an affair with Nancy Cunard but separated from her because of her preference for anal sex.

A group of his friends subscribed to a fund which would provide a monthly income to stave off his chronic financial problems. His response was to complain and insult them, whilst continuing to accept the money. He sent one of them a peremptory postcard “WHERE’S THE FUCKING STIPEND? LEWIS”

He was engaged in producing what he called his One Great Book, provisionally entitled The Man of the World, which was in fact several separate works: a study of Shakespeare, a political work on social class, and studies of contemporary youth culture and homosexuality. Not surprisingly, nobody would publish it, and the ‘book’ was split up into several separate publications. In 1926 he released both Time and Western Man (philosophy) and The Wild Body (stories).

He worked hard at promoting himself in America in the mistaken belief that he would reach a wider audience. But the market value of his paintings was falling there. By the late 1920s his domestic situation matched his fairly chaotic private life. He had rooms in two separate houses in Bayswater, one an office, the other a library. A third establishment off Portobello Road was used for painting and was kept for him by his current mistress Gladys Hoskins.

In 1930 he published The Apes of God, a huge novel consisting of lampoon portraits of characters in the London art world, including all the people from whom he had borrowed money and turned into enemies. It caused a lot of complaints, to which he responded by publishing a follow-up book of self-justification. He also got married to Gladys and visited Berlin.

On the strength of a German visit lasting less than a month, he produced an enthusiastic ‘study’ of Hitler and National Socialism This work was later to tarnish his reputation when Hitler’s ‘methods’ became better known in Britain. But at the time Lewis was on the crest of a wave with several publishing contracts in hand.

He moved to new premises in St John’s Wood, with a pokey studio in Fitzrovia. He produced more books, one on ‘Youth-politics’ [a euphemism] which libelled Godfrey Winn and Alec Waugh. When his publishers were forced to withdraw the work, he produced another on exactly the same subject with a different publisher. This did nothing to stem the tide of legal and financial claims made against him, largely for unpaid debts – including from his own solicitors.

His main financial problems were caused by demanding advance payment for books and paintings which he then failed to produce. His health suffered because of the lingering side effects of his gonorrhoea. And he brought more trouble on himself by writing libellous fictions and critical attacks on fellow artists

He had further difficulties placing his written work caused by the censorship imposed by the two influential circulating libraries – W.H. Smith and Boots the chemist. His novel The Roaring Quean attacking the Bloomsbury group was deemed unpublishable by Jonathan Cape’s lawyers.

His support for Oswald Mosley and Franco in Spain made sure he remained firmly against the tide of popular liberal opinion. Yet when his exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1937 did not attract much attention, Stephen Spender managed to gather the names of twenty (mainly leftist) artists for a letter of support in The Times.

However, his now-famous portrait of T.S. Eliot was rejected by the Royal Academy for its summer exhibition, which caused a short-lived controversy and the resignation of Augustus John as an academician.

But he did not endear himself to many people (except the Blackshirts) by publishing a book with the ridiculously provocative title of The Jews Are They Human? Whatever his political views, he left no time in sailing out of England on September 1, 1939 and emigrating to Canada – the land of his birth.

Commssions for portraits were hard to come by, so he moved on to New York where he located a literary agent John Jermaine Slocum who not only lent him money but provided a house to live in rent-free. Lewis responded to this generosity in his customary fashion: he became hostile over business arrangements and never repaid the money.

He returned with Gladys to Canada, but spent more time searching for commissions than executing them. He began looking for an ‘artist in residence’ appointment, fell on hard times, and was regularly sponging on his ex-wife Iris Barry.

Then in 1942 his luck changed. He was commissioned by Sir Kenneth Clark to produce a visual record of Canada’s activity in assisting the war effort. He also secured some public lectures via the good services of a young Marshall McLuhan who organised a slightly dubious publicity venture to lure rich patrons. He rewarded his benefactor with outbursts of paranoid hostility.

After six years abroad he returned to England the very week that the war ended. He was met by bills for unpaid rent and taxes covering the period of his absence. All efforts to resume normal productive life were hampered by post-war austerity. There was food and fuel rationing, shortage of comfort, money, and worst of all – no gin. At a physical level, his eyesight was failing, his teeth were decaying, and the apartment had dry rot.

Whilst he continued to behave in a selfish and curmudgeonly fashion to his friends and benefactors, it should be said in his favour that as art critic of The Listener he championed the causes of painters such as Robert Colquhoun, Francis Bacon, Robert MacBride, Victor Pasmore, and Ceri Richards who at that time were not well known.

The problems with his eyesight got worse, and an X-ray revealed a calcified tumour at the base of his brain. All known treatments were extremely dangerous. To make matters worse, his wife Gladys became mentally erratic and began to sink into a mild form of paranoia. Eventually he became completely blind, but continued writing, both by using a dictaphone and even writing by hand with a Biro on large sheets of paper.

Two very different twists of fortune affected his final years. Repeated conflicts with his wife led to a separation: he went to live with an old flame Agnes Bedford in Belgravia. But he was given a £250 per year pension in the Civil Lists (which Winston Churchill later increased to £500) and he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Leeds University.

Despite delays in production, his critical essay The Demon of Progress in the Arts was published, as was his late novel Self Condemned, and there was a retrospective exhibition of his paintings at the Tate Gallery which was well received.

But he felt that all these accolades had come too late. His personal life was in ruins. He was under an eviction order from the council who wanted to demolish his home and studio. And there was no let up from the tumour in his brain. It eventually killed him at the age of seventy-two.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Some Kind of Genius – Buy the book at Amazon UK

Some Kind of Genius – Buy the book at Amazon US

Paul O’Keefe, Some Sort of Genius: A Life of Wyndham Lewis, London: Jonathan Cape, 2000, pp.697, ISBN: 0224031023

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on literary studies

More on the arts