approaches to undertaking a major piece of work

Research projects

The length and purpose of research projects will depend on the level of your studies. At third year undergraduate level it might be between 3000 and 8,000 words. This might involve gathering information or making a brief investigation. An MA dissertation on the other hand is usually a longer piece of detailed academic analysis. This might be 15,000 words long or even more. A PhD thesis must be a piece of original research. Typical theses might be between 50,000 and 80,000 words long – or more.

Production

The principal difficulty is generating and handling so much material. Most people do not have the experience of assembling and writing such a long piece of work. You need to develop patience, persistence, and intellectual stamina. The material must also be given structure and coherence. You also need to present the material using the conventions of your subject-discipline.

Planning

Your essay-writing skills are your main source of support for such a task. You will need to shape and re-shape your work according to some plan or outline. This plan might change as you progress, but it will provide reassurance. Think of the work as a very big essay which will take a long time to complete. It is also likely to change both its shape and substance as you progress.

Confidence

Confidence

Despite your fears about tackling such a large piece of work, there are several reasons why you can feel confident of success. When you reach this stage you should know quite a lot about your own subject. You should now be accustomed to the language and conventions of your discipline, and aware of its principal concepts. By this stage you should also have all the basic study skills you will need. Remember that unless your project is a PhD thesis, it is unlikely that you are being asked to demonstrate dazzling originality. A research project is designed to give you the chance to show that you can make an in-depth investigation of a topic, and present your findings in an academic manner.

Form

The form of the project will depend on your subject and its conventions. It could be a review of ‘the literature’ of one aspect of your subject. It might be the writing up of a particular case study or investigation. Some reports offer the results of surveys or interviews. Others may be the records of scientific laboratory experiments. You should make yourself aware of the form of research projects in your own subject area.

Selection

Select a topic in which you are genuinely interested. This interest will help to sustain your commitment throughout the research. Completing a long piece of work is very difficult if you become bored with the topic. Be prepared to change the topic [in the early stages] if you are not happy with your first choice. Do this in consultation with your tutor or supervisor.

Topic

The best topics usually emerge from some subject you already know well. Select an item of interest which has arisen during your coursework. Do some preparatory work in narrowing down the subject to a precise focus. Don’t take on something that is too large or poorly defined. Both of these approaches will create additional difficulties. A limited project which is successful will gain more credit than an over-ambitious failure.

Examples

Study examples of other people’s successful projects. Copies of such work are usually kept in departmental libraries. Check what other topics have been covered in your subject or discipline. Discuss the possibilities with your tutor or supervisor, and with other students.

Conventions

The project is an exercise in undertaking a larger piece of work. You must also present your results in the conventional form for your subject. You are not usually expected to be dazzlingly original. You are showing that you have understood your subject, you can research a topic in some depth, and and can use the protocols of your discipline in presenting your results. Many people become very frustrated with the systems of academic quotation and referencing for instance. It’s a good idea to have full control of these at the earliest possible stage. This will save you lots of time later.

The hypothesis

Some projects begin with a clear idea, and evidence is sought to prove its validity. Alternatively, a body of work is investigated until an idea begins to emerge. You might even start from an intermediate position in which a vague hunch is pursued and revised in the light of your investigations. Each one of these approaches can be equally valid. The important thing is to be aware of which one you have chosen. The worst position to be in is floundering and uncertain, between all three.

The method

Keep relating your hypothesis to the evidence, and vice versa. Be prepared to change your hypothesis in the light of evidence if necessary. Do not be tempted to distort the evidence to prove your point. You should make the method clear to yourself first, and this will help you to explain it as part of your report or your dissertation.

Pedagogy

The extended project is used increasingly in further and higher education. It is a convenient teaching method, especially when numbers of teaching staff are getting smaller. Students learn through engagement with their materials and chosen topic. In fact it is a very efficient way of learning, because you are engaging with your subject matter in both a theoretical and practical manner. In one sense, you are teaching yourself.

© Roy Johnson 2009

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

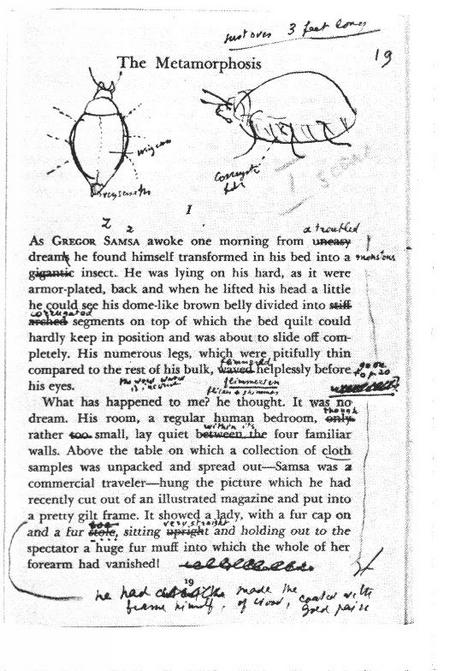

1. In preparation for writing a piece of work, you should take notes from a number of different sources: course materials, set texts, secondary reading, interviews, or tutorials and lectures. You might gather information from radio or television broadcasts, or from experiments and research projects. The notes could also include your own ideas, generated as part of the planning process.

1. In preparation for writing a piece of work, you should take notes from a number of different sources: course materials, set texts, secondary reading, interviews, or tutorials and lectures. You might gather information from radio or television broadcasts, or from experiments and research projects. The notes could also include your own ideas, generated as part of the planning process.