tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

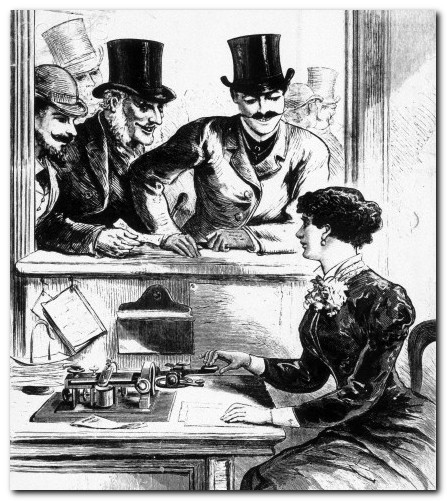

In the Cage first appeared in book form in both England and America in 1898. It was later revised and included in the complete New York edition of James’s work in 1909. The tale is quite unusual in James’s oeuvre in that it takes its subject matter from the daily life of a working-class woman. The milieu is also novel, because the events of the narrative are set in one corner of a grocer’s shop – albeit located in Mayfair.

In the Cage – critical commentary

Story? Novella? Novel?

At almost thirty-three thousand words, In the Cage is too long to be classed as a short story. It strays beyond the limits of this genre both in terms of length and subject matter. Of course James never claimed that any of his shorter fictions were short stories in the sense that this term is now used. The collective title he used for his shorter works was Tales – which turned out to be very well chosen, since this term does not carry any fixed expectations in terms of form or content.

The issue of categorisation depends very much on the interpretation given to the content of the piece. If it is regarded as an innocent and brief interlude during the summer months of a young woman’s life, it would be quite legitimate to classify it as a long short-story. She indulges in an imaginative romance, but then settles for a safe if predictable marriage.

But if the issues of modern telegraphy, transmitting messages, the different expectations and behaviour between working and liesured classes, and the educative process of the young woman’s lesson in realism are taken into account – a case could be made for it being a short novel. These are large enough issues to warrant classification in the heavier and more serious genre.

However, in even a short novel we would normally expect a more even-handed and fully rounded account of the principal characters. In the Cage provides characterisation for only the young woman, her friend Mrs Jordan, and her fiancé Mr Mudge. We really know very little about Captain Everard and almost nothing about Lady Bradeen except through the imagination of the young woman or the social gossip of Mrs Jordan. This is not the substance we expect of the realist novel, no matter how foreshortened.

That leaves the possibility of classifying the work as a novella. The tale certainly has a number of the ingredients we expect to find in the genre that James particularly admired – what he called “the beautiful and blessed nouvelle“. . Novellas are like simplified and densely compressed novels, with few characters and an intensely concentrated subject which usually has universal significance.

Narrative interest in this tale is focussed on the educative experience of one character – the young woman telegraphist. The location (apart from one brief holiday excursion) is largely her commercial environment in Mayfair and the pressure she is under from social conditions at work and home. Her professional skills working with contemporary technology are a fitting symbol for communications between the classes which form the backbone to the narrative. And it could be argued that her final decision to realistically accept her fate as the wife-to-be of a grocer is a universal theme.

On all these grounds In the Cage qualifies as a novella. But there are some problems with this interpretation which fits the tale to this genre.

Problems

Foremost is the issue of inevitability. The novella (and even the novel) does require a certain degree of persuadable, logical, inevitable outcome from the premises it has laid forward. It also has to be said that most novellas have a very serious, and often a tragic outcome: one thinks of classics in the genre, such as Benito Cereno, Death in Venice, and even James’s own The Turn of the Screw, which was written in the same year.

The problem with In the Cage is that the young lady, for the majority of the narrative, is a hopelessly romantic fantasist – imputing all sorts of characteristics and motives to her customers without any supporting intelligence. James deliberately satirises this attitude, as he does the comparable snobbery and pretention of Mrs Jordan. What he does not really supply is sufficient evidence for her change of heart when she decides to settle for marriage to Mr Mudge.

Quite apart from his semi-comic name, Mr Mudge has been characterised throughout the tale as a well-intentioned man but a monumental bore of Dickensian proportions. He represents a realistic marriage prospect for a young woman of the telegraphist’s position in society – but since we have been made aware of his shortcomings largely from her point of view throughout the narrative, her conversion to accepting him at its end doesn’t seem altogether persuasive. Neither is such a resolution the substance of the novella, which normally deals in serious issues. The future for Mr and Mrs Mudge in Chalk Farm is nothing more than the prospect of a life of unremitting Pooterism, The Diary of a Nobody having been published only a few years earlier in 1888). This sort of bathetic outcome is not normally the substance of a novella.

On these grounds, it might be safer to simply leave In the Cage categorised as the completely amorphous Tale, a long story of sorts (which is more or less the same thing), or a very short novel. It is interesting to note that it is placed in all these categories by members of the book trade such as Amazon and AbeBooks.

In the Cage – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1892—1898 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1892—1898 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 18—18 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 18—18 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() In the Cage – Kindle edition

In the Cage – Kindle edition

![]() In the Cage – eBook versions at Gutenberg

In the Cage – eBook versions at Gutenberg

![]() In the Cage – audioBook versions at LibriVox

In the Cage – audioBook versions at LibriVox

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

In the Cage – plot summary

Part I. An un-named young woman works as a telegraphist in the post office within a grocer’s store in Mayfair. She has become engaged (without much enthusiasm) to Mr Mudge, a grocer, and she lives in rather poor circumstances with her mother and her elder sister.

Part II. Her fiancé wants her to move to an ‘outer suburb’ (Chalk Farm) so as to be nearer to him, and to save money. But she prefers to stay in Mayfair, the social life of which gives her scope for her imagination.

Part III. She despatches telegrams and cryptic messages, and she fantasises about the lives of her customers – particularly a ‘handsome lady’ who might be called Mary or Cissie.

Part IV. She interprets the lives of her customers from the contents of their telegrams – particularly a man who comes in with the handsome lady, who she assumes to be the ‘Everard’ mentioned in some messages.

Part V. She is very conscious of class differences and the profligate way her (largely upper-class) customers spend their money (judging by the length of their messages – which are priced per word). She feels powerful in knowing people’s secrets and she generalizes that her women customers are on the whole in pursuit of her men.

Part VI. Her friend Mrs Jordan invites her to join her flower-arranging enterprise, which she enjoys because it brings her into contact with upper class society.

Part VII. She is tempted by the idea, because she wants to meet people from the upper class. Mrs Jordan claims to be on intimate terms with her clients, but it is clear that she is exaggerating any such connections.

Part VIII. The two women begin to compete over who has the closer connections with fashionable society. The young woman also begins to have doubts about her engagement to Mr Mudge.

Part IX. She has mixed feelings about Mr Mudge, who is boring and predictable, yet she respects his simplicity and honesty. She can see his limitations, and she aspires to ‘greater’ (more romantic) things.

Part X. She tells Mr Mudge that she is appalled by the rich people who are her customers, but it is clear that she feels a snobbish pleasure at ‘mixing’ with upper class society. He too is attracted to the idea of rubbing shoulders with the well-to-do.

Part XI. Meanwhile,, she continues to inflate the significance of her (non) ‘relationship’ with Captain Everard. She invents excuses for querying his written notes, but sees them as having been planted there deliberately for that purpose.

Part XII. She imagines that Captain Everard would like to share his problems with her and confide in her about his love affairs. She goes to the building at Park Chambers where he lives and fantasises about meeting him.

Part XIII. The handsome lady returns, and she helps her to correct a mistake in her telegram, which reveals her knowledge of the lady’s affairs.

Part XIV. When the summer arrives Mr Mudge wants to plan a holiday together. She is bored by the excessive details of his preparation, and starts walking past Park Chambers every night. On one occasion she does meet him there.

Part XV. They walk into Hyde Park and sit on a bench together, talking. He reveals that he knows she has been taking a ‘special interest’ in him, which makes her cry.

Part XVI. Thinking that she is unlikely to meet him again, she tells him the whole truth of the interest she has taken in him, but that she will be leaving to work elsewhere. He asks her to stay and ‘help’ him.

Part XVII. She admits to him that she enjoys knowing about people’s private lives and says she will do anything for hi. He implores with her to stay working in the post office, and she leaves him saying that she will never give him up.

Part XVIII. She goes on holiday to Bournemouth with her mother and Mr Mudge, where he is more boring than ever, but she retreats from him into a private world of the imagination. However, he announces that having been given a rise at work, he is now ready to marry.

Part XIX. She relates her recent experiences in the Park with Captain Everard to Mr Mudge, and explains how she wants to protect him from danger. She also wants Mr Mudge to wait longer before they marry – at which Mudge is (understandably) miffed.

Part XX. Some weeks later Captain Everard returns to the post office. She feels that something is wrong, and possibly reaching a dramatic climax. Everard lingers in the shop, but they do not get a chance to speak to each other.

Part XXI. The same thing happens again later. She persuades herself that Everard is somehow trying to help her. She also interprets all his telegrams as signs of danger of some kind.

Part XXII. She thinks her services as Everard’s protector will come to an end, and she will be obliged to accept Mr Mudge. However, the very next day Everard arrives with an urgent telegram. Next day he comes back again saying he wants to recover a telegram sent some time ago.

Part XXIII. She procrastinates in trying to locate the telegram for him, but in the end supplies the information he needs. She has memorised it, because of her interest in his correspondence.

Part XXIV. During the late summer low season Mrs Jordan continues to boast about her connections with high society. She invites the young woman back to her humble rooms in Maida Vale. She is engaged to marry Mr Drake.

Part XXV. Mrs Jordan reveals that Mr Drake is due to be engaged (as a butler) by Lady Bradeen – who is a correspondent of Captain Everard’s via his telegrams. Lady Bradeen is due to marry Captain Everard, following quickly on the death of her husband. The two women ‘compare’ impressions of Lady Bradeen – who neither of them know.

Part XXVI. The two women then compare their own marriage prospects comeptatively. The young woman realises that they are both doomed to live in obscurity. Nevertheless, compared to Mrs Jordan, she feels fortunate.

Part XXVII. Mrs Jordan then reveals that Captain Everard has no money at all, but lots of debts, and was involved in a social scandal from which Lady Bradeen saved him – but forced him to marry her as the price for doing so.

The young woman departs, more glad than ever to have the prospect of her own home and marriage to Mr Mudge.

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Daisy Miller (1879) is a key story from James’s early phase in which a spirited young American woman travels to Europe with her wealthy but commonplace mother. Daisy’s innocence and her audacity challenge social conventions, and she seems to be compromising her reputation by her independent behaviour. But when she later dies in Rome the reader is invited to see the outcome as a powerful sense of a great lost potential. This novella is a great study in understatement and symbolic power.

Daisy Miller (1879) is a key story from James’s early phase in which a spirited young American woman travels to Europe with her wealthy but commonplace mother. Daisy’s innocence and her audacity challenge social conventions, and she seems to be compromising her reputation by her independent behaviour. But when she later dies in Rome the reader is invited to see the outcome as a powerful sense of a great lost potential. This novella is a great study in understatement and symbolic power.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories