tutorial, synopsis, commentary, and study resources

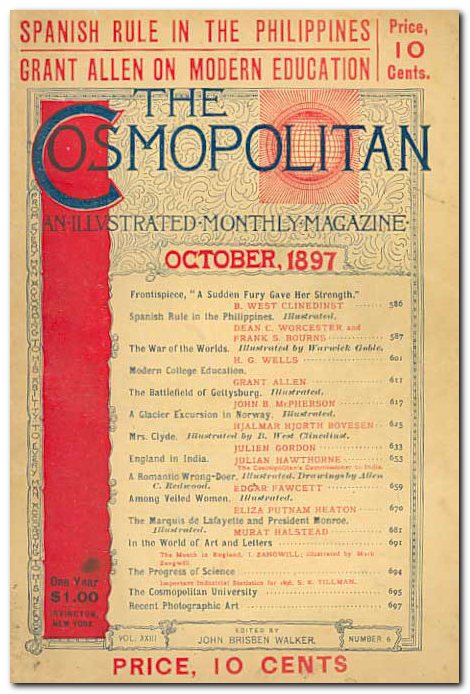

An Outpost of Progress was written in July 1897 and first appeared in the magazine Cosmopolitan in 1897. Quite amazingly, given the subject of the story, this was a magazine which began as a ‘family magazine’ and eventually became a magazine for women. In the late nineteenth century however, it was a leading outlet for literary fiction, publishing stories by Rudyard Kipling, H.G. Wells, Edith Wharton, Theodore Dreiser, and other leading contemporary writers. The first appearance of An Outpost of Progress in book form was as part of the collection Tales of Unrest published in 1898. The other pieces in this collection were Karain: A Memory. The Idiots. The Return. and The Lagoon.

Cosmopolital Magazine – October 1897

An Outpost of Progress – story synopsis

Part I. An unsuccessful painter has been established as chief of a trading outpost somewhere in Africa. When he dies of a fever his replacement is Kayerts, with Carlier as assistant. However, the business is actually run by Makola, who is from Sierra Leone. The director of the trading company thinks the two men he has been sent are quite useless. They themselves feel vulnerable, being cut off from civilization, and each hopes the other will not die, because they would not like to be left alone.

Kayerts is there to earn a dowry for his daughter: Carlier has been sent there by his family because he has no money and is completely idle. They make a perfunctory attempt to improve their sparse quarters, then give up, taking no interest at all in the life that surrounds them. Makola conducts all trade with the local population, swapping ivory for cheap rubbishy European goods.

The two men get caught up childishly in their reading of novels by Dumas, Fennimore Cooper, and Balzac that the director has left behind. They are supported by (and dependent upon) produce donated by Gobila, the chief of a nearby village.

One day they are visited by a menacing group of strangers carrying weapons. The two men do not know what to do – so Makola deals with them but does not report the results. That night there is a lot of drumming and gunshots are heard.

Part II. The station has a staff of native workers who come from a distant tribe. Makola reports that the armed traders (who are from Luanda) wish to sell some ivory. The next night the workers are given palm wine and Makola trades them as slaves for the ivory. One of Gobila’s men is shot in the process. Kayerts and Carlier protest their outrage, but do nothing. Gobila and his villagers cut off relations (and supplies) with the station.

Since the two men are incapable of finding their own provisions, they begin to deteriorate physically. They are hoping for a visit from the company steamship for supplies, but it does not appear. Then they have a dispute over a trivial issue regarding some remaining lumps of sugar. They chase each other around the outside of the house, but Kayerts has a revolver, and ends up shooting Carlier by accident. Makola has witnessed the scene: they agree to report that Carlier died of a fever and he will be buried next day.

Next morning the station is engulfed in mist. Kayerts awakes to find Carlier’s body next to him, and he panics with fright. At the same moment the company steamer arrives on the river, and Kayerts fears that civilization is coming to judge and condemn him. He commits suicide by hanging himself on the cross marking his predecessor’s grave.

An Outpost of Progress – study resources

![]() An Outpost of Progress – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

An Outpost of Progress – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() An Outpost of Progress – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

An Outpost of Progress – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle eBook

![]() An Outpost of Progress – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

An Outpost of Progress – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() An Outpost of Progress – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

An Outpost of Progress – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() An Outpost of Progress – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

An Outpost of Progress – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

An Outpost of Progress – principal characters

| Kayerts | the new chief of the trading station – fat, small |

| Carlier | his assistant – tall with thin legs |

| Makola (Henry Price) | native clerk, from Sierra Leone |

| Mrs Price | his wife, from Loanda |

| Gobila | neighbouring village chief |

An Outpost of Progress – commentary

These are the opening lines of the story. The notes which follow offer a detailed interpretation or close reading.

There were two white men in charge of the trading station. Kayerts the chief, was short and fat. Carlier, the assistant, was tall, with a large head and a very broad trunk perched upon a long pair of thin legs.The third man on the staff was a Sierra Leone nigger, who maintained that his name was Henry Price. However, for some reason or other, the natives down the river had given him the name Makola, and it stuck with him through all his wanderings about the country. He spoke English and French with a warbling accent, wrote a beautiful hand, understood book-keeping, and cherished in his innermost heart the worship of evil spirits. His wife was a negress from Loanda, very large and very noisy. Three children rolled about in sunshine before the door of his low shed-like dwelling. Makola, taciturn and impenetrable, despised the two white men. He had charge of a small clay storehouse with a dried grass roof, and pretended to keep a correct account of beads, cotton cloth, red kerchiefs, brass wire, and other trade goods it contained. Besides the storehouse and Makola’s hut, there was only one large building in the cleared ground of the station. It was built neatly of reeds, with a verandah on all the four sides. There were three rooms in it. The one in the middle was the living-room, and had two rough tables and a few stools in it. The other two were the bedrooms for the white men, Each had a bedstead and a mosquito net for all furniture. The plank floor was littered with the belongings of the white men: open half-empty boxes, torn wearing apparel, old boots; all the things dirty, and all the things broken, that accumulate mysteriously around untidy men. There was also another dwelling-place some distance away from the buildings.

A close reading

1. ‘There were two white men in charge of the trading station.’

This is very typical of Conrad’s use of dramatic irony – because we rapidly learn that the two men are only nominally in charge. It is their assistant Makola who really does all the work and determines what goes on, whilst they are hopelessly incompetent. The term ‘white men’ is significant because the story is set against the political background of the exploitation of black Africa by white Europeans.

2. The two names Kayerts and Carlier suggest that the story is set in the Belgian Congo. Kayerts is a Flemish name, and Carlier is French, these being the two linguistic groups which comprise Belgium. The physical description of the two men emphasises their difference in the manner of comic music-hall double acts (of the Laurel and Hardy, Little and Large variety). And the term perched in ‘a very broad trunk perched upon a long pair of thin legs’ is belittling and quasi-comic.

3. ‘Sierra Leone nigger, who maintained his name was Henry Price’

The use of the term ‘maintained’ suggests just the opposite – that Makola has given himself the name Henry Price because he wants to identify his interests with those of his employers. Conrad’s use of the term ‘nigger’ would not be remarkable in 1897 when the story was written.

4. The natives call him ‘Makola’ – and so does Conrad, which reinforces the reading of the previous sentence. His ‘wanderings’ suggest that he is confident and experienced.

5. Makola speaks two European languages in addition to his own African language and his wife’s (which is very likely to be different). He is also a skilled clerk. Thus he has absorbed European culture, in contrast to the two Europeans who are completely incapable of absorbing his. Yet he still worships evil spirits. In other words, he has a foot in both cultures.

6. His wife is from Loanda, which is on the coast of Angola, close to what was once called the ‘Slave Coast’. This is why she understands what the slave traders are saying later in the story.

7. ‘Rolled about’ suggests that the children are at ease in their natural environment. ‘Shed-like’ tells us the poor state of their accommodation.

8. ‘Impenetrable’ is a typical Conradian term – abstract and quasi-philosophical. It tells us that Makola keeps his feelings and his motivation well hidden. It is a similar type of term to those Conrad uses later to describe the topographical setting of the story – ‘hopeless’, ‘irresistible’, and ‘incomprehensible’. Such details contribute to the reason why Africa in a moral sense defeats the two Europeans in the story. The term ‘despised’ however is a key insight into Makola’s judgement and feelings: this points to the element of racial conflict in the story.

9. The ‘trade goods’ in which the station deals are in fact cheap rubbish, and they are being exchanged for ivory, a highly valued item in Europe. The exchange is therefore unfair, and the Africans are being cheated. But the term ‘pretended’ suggests that Makola might be engaged in a little cooking-of-the-books on his own account.

10. The ‘one large building’ reveals just how undeveloped this trading station is, at the same time as emphasising its isolation. The ‘verandah’ which goes round all four sides will be an important feature in the later part of the story when Kayerts is chasing Carlier round the house.

11. The mosquito nets would be important, because the two men are close to the equator, and therefore a long way away from their European homeland. Moreover, the previous chief of the trading post has died of fever.

12. The two men do not know how to look after themselves. The floor of the building is ‘littered’ with their ‘broken’ and ‘dirty’ goods. We also learn that they have come equipped with ‘town wearing apparel’ which is completely inappropriate for living in the tropics.

13. The other ‘dwelling place’ nearby is another example of Conrad’s scathing irony. For this place is the grave of the first station chief. Africa has already killed off one representative of Europe when the story opens – and it will claim two more before it ends.

Joseph Conrad – video biography

Conrad’s literary style

In his introductory notes to the collection Tales of Unrest in which An Outpost of Progress appeared, Conrad gives a clear indication that he was aware of breaking new ground in his writing:

almost without noticing it, I stepped into the very different atmosphere of An Outpost of Progress. I found there a different moral attitude. I seemed able to capture new reactions, new suggestions, and even new rhythms for my paragraphs.

It is certainly true that from the late years of the nineteenth century onwards, Conrad developed his very idiosyncratic prose style – one which many people find difficult to follow. His sentences become longer and longer; he uses a rich and sometimes abstract vocabulary; he is much given to quasi-philosophic intrusions into his own narrative; and in some of his novels he uses multiple narrators and a radically fractured chronology of events.

What follow are a series of notes on his style, based on a further passage from An Outpost of Progress.

The two men watched the steamer round the bend, then, ascending arm in arm the slope of the bank, returned to the station. They had been in this vast and dark country only a very short time, and as yet always in the midst of other white men, under the eye and guidance of their superiors. And now, dull as they were to the subtle influences of surroundings, they felt themselves very much alone, when suddenly left unassisted to face the wilderness; a wilderness rendered more strange, more incomprehensible by the mysterious glimpses of the vigorous life it contained. They were two perfectly insignificant and incapable individuals, whose existence is only rendered possible through the high organisation of civilised crowds. Few men realise that their life, the very essence of their character, their capabilities and audacities, are only the expression of their belief in the safety of their surroundings. The courage, the composure, the confidence; the emotions and principles; every great and every insignificant thought belongs not to the individual but to the crowd: to the crowd that believes blindly in the irresistible force of its institutions and of its morals, in the power of its police and its opinion. But the contact with pure unmitigated savagery, with primitive nature and primitive man, brings sudden and profound trouble to the heart. To the sentiment of being alone of one’s kind, to the clear perception of the loneliness of one’s thoughts, of one’s sensations — to the negation of the habitual, which is safe, there is added the affirmation of the unusual, which is dangerous; a suggestion of things vague, uncontrollable, and repulsive, whose discomposing intrusion excites the imagination and tries the civilised nerves of the foolish and the wise alike.

Sentence length

Some of the sentences here (particularly the last) are quite long. This is because he is expressing complex ideas or generating a charged atmosphere. These are what some people find difficult to follow. But they are not all long: the first, for instance, dealing with a simple action by characters, is much shorter.

Paragraph length

Conrad’s paragraphs in general are quite long – which was common in the literature of the late nineteenth century. The first part of this paragraph describes what the two characters are doing and what they are feeling; but from the sentence beginning ‘They were two perfectly insignificant and incapable individuals’ the paragraph content switches to quasi-philosophic reflections and generalisations about human behaviour.

Narrative mode

This story is written in what’s called the ‘third person omniscient narrative mode’. That is, Conrad tells us what his characters do, what they think, and how they feel. He is in charge of the entire story, and he also provides an account of the inner lives of his characters.

But from the sentence beginning ‘Few men realise …’ the narrative mode changes. The statements which follow – right up to the end of the paragraph – are generalised observations about life and human behaviour. These opinions are not attributed to the characters (who are fairly stupid people anyway) but are offered as if they were universal truths to which any sane person would agree.

Conrad here is slipping into an unacknowledged or disguised form of first person narrative. The opinions about how human beings react to ‘primitive nature and primitive man’ are Conrad’s own opinions – but he offers them in such a subtle and powerful manner that only a careful and alert reader will notice.

Conrad here is being what is called an ‘intrusive narrator’ – weaving his own philosophy of life into the narrative. And because he is the author, in complete charge of the text, he can make his evidence in the events of the story fit the assertions he is offering. Such is the magic of imaginative literature.

But it is worth noting these shifts in narrative mode – particularly in the case of Conrad, because in many of his longer stories and his novels he manipulates the delivery of narratives in an even more complex fashion – and sometimes gets himself into trouble: (see Freya of the Seven Isles, Nostromo, and Chance for instance).

Language

You will probably have noticed that Conrad uses a number of very charged terms in his evocation of milieu in which his two characters find themselves – terms such as ‘irresistible force’, ‘unmitigated savagery’, and ‘negation of the habitual’. What makes these difficult to grasp at first is that he is switching from the very specific and concrete description of the two men and the trading station to an abstract and very general consideration of their condition. This is almost the language of philosophy – and it is certainly a change of register.

The terms ‘force’, ‘savagery’, ‘habitual’, and ‘intrusion’ are all abstract nouns which draw readers’ attention away from the overt ‘story’ and force them to consider rather large scale social reflections on life.

In fact the combination of a rather unusual and powerful adjective qualifying an abstract noun — ‘unmitigated savagery’ and ‘profound trouble’ — is a sort of trade mark of Conrad’s literary style. You will see many other examples in this story and throughout his work in general.

Prose rhythm

In prose fiction rhythm is easier to feel than to define, but it should be fairly clear that Conrad puts a lot of rhythmic emphasis into his writing by his use of alliteration, repetition, and what are called balanced phrases and parallel constructions.

For instance ‘The courage, the composure, the confidence’ is a fairly obvious use of alliteration, with an insistent stress falling on the initial letter c in each of these words (which are all abstract nouns).

He uses both repetition and parallel construction in ‘To the sentiment of being … to the clear perception … to the negation of the habitual …’ – which helps the reader through a very long sentence.

Syntax

The term ‘syntax’ is used to describe the order of words in a sentence and the logic of their connection. These are normally determined by the long traditions and the historical development of the language itself. But Conrad is often given to unusual constructions — such as ‘The director was a man ruthless and efficient’.

This isn’t wrong or grammatically incorrect, but in conventional English adjectives are usually placed before the nouns that they qualify — as in ‘The director was a ruthless and efficient man’.

But English was Conrad’s third language after Polish and French, and he often uses constructions which are influenced by or echoes of his first and second languages.

Joseph Conrad’s writing

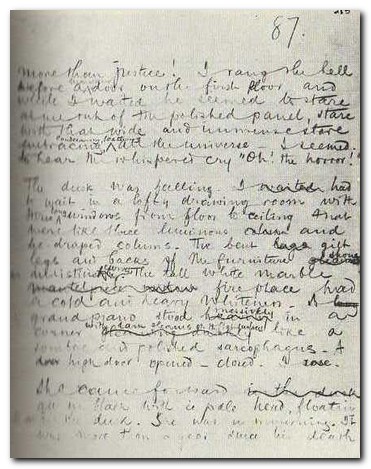

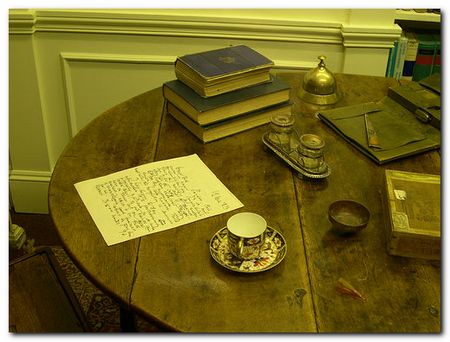

Manuscript page from Heart of Darkness

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Other writing by Joseph Conrad

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Joseph Conrad links

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

Joseph Conrad complete tales