tutorial, study guide, critical commentary, further reading

The Kingdom of this World (1949) is Alejo Carpentier’s historical novel documenting the first successful slave revolution in the Americas. It took place on the island of Hispanola in what is now Haiti between 1791 and 1804. The story is told largely from the point of view of a poor slave, and it unfolds in a series of amazingly vivid tableaux that capture both the confusion of political upheavals and the complexities of European colonialism in the New World. It is generally considered Carpentier’s first great novel.

The Kingdom of This World – commentary

Historical background

The islands that make up the Antilles were first visited (‘discovered’) by Christopher Columbus in 1492. He was making his journey westward in search of spices and gold, and he thought he had landed in China or India. That’s why the area is known as the West Indies.

His journey was quickly replicated by the British and the French. All of these European nations claimed ownership wherever they landed. And they were meanwhile at war with each other. At this time even America was a colony ‘belonging’ to England.

Having established political and military control over the islands, the next phase of European colonial expansion was to import slaves from Africa to do the work of exploiting the natural resources of the islands – the sugar cane, tobacco, and minerals. Much to the chagrin of Columbus, there was no gold. Carpentier gives a vivid account of this episode in his other novel The Harp and the Shadow (1979).

The events of The Kingdom of This World take place on Hispanola in the Caribbean, an island which is split into two separate countries – Haiti and San Domingo. The political history of the region is quite complex. Haiti was then a French colony, whilst San Domingo was under Spanish domination.

The French regarded the island as a colony, but during the French Revolution there was a humanitarian decision made in Paris that slavery should be abolished. Hispaniolan slave leaders such as Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines took advantage of this, seized power, and declared the first ever black republic. Napoleon Bonaparte sent troops (such as Leclerc) to crush the rebellion, but they lost two thirds of their forces – largely due to cholera.

Voodoo

The slaves imported from West Africa brought with them a form of witchcraft that in Haiti became known as Voodoo. Like other religions this is founded on a belief in a supreme and unknowable creator. It has ritualistic ceremonies, a hierarchical system of priests, a belief in evil spirits, talismanic icons, reincarnation, trance-like states, and the sacrifice of animals.

When the colonial authorities tried to impose Christianity on the slaves, they merely incorporated European saints, altars, holy water and votive candles into their rituals. They also used religious celebrations as covert political meetings to strengthen their bonds of allegiance. The fictional character Boukman was a real historical person and religious leader who helped to prepare the 1791 revolt against the French.

Magical realism

Carpentier incorporates these elements of mystical beliefs into his narrative quite naturally, using the device he called ‘magical realism’. That is, elements of rational, material, and realistic depiction of the world are mixed with fanciful, non-realistic elements such as the slaves’ belief that Macandal can change himself into a bird or an animal to evade capture.

Their belief is a metaphoric reflection for the hope of salvation being kept alive in a community. Despite their beliefs, Macandal is eventually captured and executed horribly by being burned alive in an auto-da-fe. Carpentier thus combines his modernist technique of el real maravilloso with a realistic and historically accurate account of events. It is the past re-imagined and expressed in a literary style that combines some of the traditional elements of the realist novel with modernist techniques of a particularly Latin-American flavour.

Literary style

It should be obvious from even a cursory reading of Carpentier that he delivers his narrative in a manner that is radically different from conventional European novels of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

For instance there is less emphasis on the psychology and the emotional experience of individual characters. He is more interested in providing an overview of events – of showing historical forces at work.

In addition he does not create a continuous narrative, with events following in detailed chronological sequence. Instead, he arranges his scenes as a series of tableaux which represent, either symbolically or metaphorically, the important stages of historical development.

For example, the sudden emergence and even more rapid death of General Leclerc at first appears somewhat arbitrary. He had not been mentioned before this brief appearance. But he represents the counter-revolutionary forces sent by Napoleon to quell the revolution. Leclerc is on a ship with a cargo of savage dogs that will be used to track down and terrorise slaves.

But Leclerc does not complete his commission – because he dies of cholera. This might appear to be another accidental episode to an inconsequential character. It is not – because Leclerc represents the French government’s counter-revolutionary forces – two thirds of whom died of cholera in their attempt to repress the slave revolt.

The narrative

A great deal of the novel is related from the point of view of Ti Noel, who is an uneducated slave with no material possessions. He starts out enslaved on the de Mezy plantation; he takes part in the uprising; and he even thinks of raping de Mezy’s French mistress – though it is not made clear if he does or not.

He is eventually sold on to another slave owner in Santiago de Cuba. Technically, he then becomes a free man, but on return to Haiti he is enslaved anew during the construction of the fortress by the new ‘King’ Henri Christophe I.

When the ‘King’ is in his turn overthrown, Ti Noel returns to the former, now devastated de Mezy plantation and and lives in makeshift accommodation amongst the ruins. Many critical commentators have seen this sequence of events as Carpentier offering a cyclic view of history. That is, when one system of oppression is overthrown by a revolution, it will be replaced by another system imposing a similar tyranny under a different name.

This is a short-sighted view in my opinion that does not take into account Carpentier’s generally positive view of social development. It certainly does not take into account the heroic epiphany which is accorded to Ti Noel in the finale of the novel – in which he replaces his former religious views with one which takes a realistic and material view of the world.

In the Kingdom of Heaven there is no grandeur to be won, inasmuch as there all is an established hierarchy, the unknown is revealed, existence is infinite, there is no possibility of sacrifice, all is rest and joy. For this reason, bowed down by suffering and duties, beautiful in the midst of his misery, capable of loving in the face of afflictions and trials, man finds his greatness, his fullest measure, only in the Kingdom of This World.

The Kingdom of This World – study resources

The Kingdom of This World – at Amazon UK – (text in English)

El reinido de este Mundo – at Amazon UK – (text in Spanish)

The Harp and the Shadow – at Amazon UK – (text in English)

El arpa y la sombra – at Amazon UK – (text in Spanish)

The Kingdom of This World – plot summary

Part One

I Poor black slave Ti Noel compares feeble European rulers with the warrior kings of his African ancestors.

II Macandal’s arm is crushed in the de Mezy plantation sugar mill – then amputated.

III Macandal collects herbs and poisonous plants, then takes them to a Voodoo witch. He poisons a dog, then runs away.

IV Ti Noel misses Macandal’s African influence. He finds him hiding in the mountains, having made contact with other resistance fighters. Macandal begins to spread poison in the plantations

V The poisons spread, killing animals and humans alike. Slaves are tortured until one reveals that Macandal is the culprit.

VI There is a search for Macandal but he is not found. People believe he can change his form into that of birds and animals.

VII Four years later M. de Mezy remarries at Christmas. Ti Noel attends a Voodoo ritual celebration where Macandal reappears in human form.

VIII Slaves are herded into the town square to witness Macandal being burned alive. They believe his spirit escapes in a different form.

Part Two

I In twenty years the island prospers. M. de Mezy imports a French actress as a mistress but continues raping slave girls. Ti Noel keeps the memory of Macandal alive.

II Ti Noel attends a meeting at which Bouckman brings news of freedom won in the French revolution. They seek help from the Spanish in adjacent San Domingo.

III A general revolt against the whites takes place. The slaves pillage de Mezy’s house and estate.

IV de Mezy finds Mlle Floridor murdered in the house. The revolt is supressed, with severe reprisals. Ti Noel is spared for his re-sale value.

V de Mezy escapes to Santiago de Cuba along with other landowners. He sells off his slaves and gambles away the proceeds.

VI Self-indulgent Pauline Bonaparte arrives from France with her husband General Leclerc who is to put down the revolt.

VII General Leclerc contracts cholera and dies. His wife Pauline returns to France.

Part Three

I Ti Noel returns from Cuba to Haiti as a free man.

II Ti Noel arrives at the magnificent palace of Sans Souci built for the new ‘King’ Henri Christophe.

III Ti Noel is forced into a new form of slavery – building the Citadel La Ferriere which Henri Christophe constructs as a bulwark against the French.

IV When the Citadel is finished Ti Noel returns to live in the remains of the de Mezy estate. He travels to Cap Haitien but the city is in the grip of fear. Henri Christophe has buried his personal confessor alive.

V The confessor reappears at a mass, and the King falls into a terrified spasm, afraid that the people will rise against him.

VI A week later there is a revolt of the King’s officers, and Henri Christophe is stranded alone in Sans Souci. He watches from the palace as the fires and the insurgents close in on him. He dresses in ceremonial uniform then shoots himself.

VII The queen and her retinue escape to the fortress whilst the palace is being looted. The king’s body is submerged in a vat of mortar then intered as part of the Fortress

Part Four

I The queen and princesses escape to Rome with Solimon. He is an object of curiosity in the city. In the Villa Borghese he comes across a statue of Venus modelled by Pauline Bonaparte. The experience unnerves him, and he wants to go home again. He dies dreaming of his African roots.

II Ti Noel equips his makeshift lodgings with furniture looted from Sans Souci. He dresses in Henri Christophe’s old uniform and imagines himself the ruler of a kingdom.

III Mulatto surveyors arrive to take over the land. Ti Noel tries to hide from them by assuming various animal forms.

IV Ti Noel contemplates the geese that have escaped from Sans Souci. He then has an epiphany that man finds his greatness by suffering and enduring in the real world, not in some imaginary afterlife.

The Kingdom of This World – characters

| Ti Noel | a black slave on the de Mezy plantation |

| Lenormand de Mezy | the French plantation owner |

| Macandal | a black slave and freedom fighter |

| Bouckman | a Jamaican slave |

| Mlle Floridor | de Mezy’s French mistress, a failed actress |

| Henri Christophe | a cook who becomes the first ‘King’ of Haiti |

| General Leclerc | a French soldier sent to quash the slave revolt |

| Pauline Bonaparte | his self-indulgent and adulterous wife |

| Soliman | Pauline’s black slave and masseur |

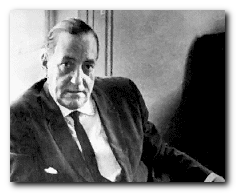

© Roy Johnson 2018

More on Alejo Carpentier

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Chase

The Chase

The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps