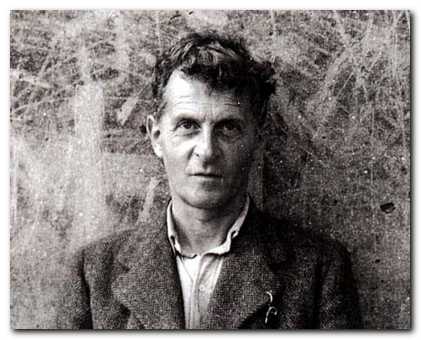

portrait of the tortured Anglo-Austrian ‘genius’

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) was born into an aristocratic and fabulously wealthy family in Vienna at a time when it was the epicentre of the Hapsburg empire. The family was Jewish, but had largely converted to Christianity. It provided a very rich cultural and intellectual environment – Brahms, Mahler, Klimt and Schiele were family friends. Ludwig was the youngest of eight very talented children but was regarded in comparison as not very bright. He studied at the same secondary school in Linz as Adolf Hitler, did poorly in most subjects, lost any scraps of religious belief. and came under the influence of Schopenhauer, Karl Kraus, and the anti-Semitic misogynist work Sex and Character by Otto Weininger, a homosexual and Jew who became a cult figure following his suicide at the age of twenty-three.

Even though Wittgenstein’s first thoughts about philosophy began in his late teenage years he continued his studies in engineering (under his father’s influence) and in 1908 went to Manchester to study the very young discipline of aeronautics. He invented an early form of jet engine and even patented the design for a propeller – but his real interest had been piqued by reading Bertrand Russell’s The Principles of Mathematics. In 1911 he introduced himself to Russell at Trinity College Cambridge – a meeting which was to be decisive for both of them. He gave up engineering and the following year became Russell’s student.

Bertrand Russell

The relationship between them was complex and emotional. Russell regarded Wittgenstein as his intellectual successor in the study of philosophy, but quickly tired of his self-obsessed rantings and his neurotic behaviour. As a recognised ‘genius’ ( though still only twenty-four and an undergraduate student) Wittgenstein was immediately proposed as an Apostle – but he resigned the honour just as immediately, despite the support and continued sponsorship of the prestigious John Maynard Keynes.

Wittgenstein formed a close bond with fellow student David Pinsent – and given what we know of his later homosexuality it is difficult to escape the suggestion that a great deal of his lacerating self-criticism and worries about ‘sin’ and ‘one great flaw’ are attributable to repressed homo-eroticism. They took a holiday together in Norway which was full of emotional scenes, fallings-out, and reconciliations.

Meanwhile, Russell’s work on the fundamentals of logic was abandoned because of Wittgenstein’s criticisms. Russell handed over the baton to his student, his own confidence completely shattered. Wittgenstein developed the neurotic idea that he was shortly going to die, and that in order to complete his great work he must cut himself off from society and live alone like a hermit. This also included leaving Cambridge, so he went to live in a remote Norwegian village for a year, submerged himself in logic, put his relationship with Russell on a cooler footing, and immediately started paying court to G.E. Moore, who was a central figure at Cambridge following the success of his Principia Ethica in 1903.

However, when he discovered that his work on logic could not be submitted for his B.A. degree (because it entirely lacked a preface, structure, examples, and critical aparatus) he took out his anger on the unsuspecting Moore, and the two of them did not speak again for fifteen years. Following this disappointment he returned home to Vienna and gave large sums from his personal fortune to literary artists and painters whose work he did not know at all.

The soldier

At the outbreak of war in 1914 he immediately enlisted in the army but since Austria was at war with Britain he found himself on the opposite side to all his friends. He served in a variety of menial roles for a year before he was granted his fervent wish – to go to the front and face death. He did face it – and behaved with conspicuous bravery. It is amazing to note that despite his active military service, he continued to work on what became his magnum opus, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. But he also changed its original purpose: the final work on symbolic logic was blended with reflections on religious mysticism, which is one of the reasons why the work is still so difficult to understand. But his death wish was denied him. He was taken prisoner by the Italians at Monte Cassino and was not released until August 1919.

After the war, he was a changed man. He continued to wear his army uniform (of a state that no longer existed) ; he gave away all his money to his brothers and sisters (who were already enormously wealthy); and he enrolled to train as an infant school teacher. He could not get his book published (or understood) and he was beset by repeated thoughts of suicide as he grappled with his inner daemons . (It’s worth noting that three of his brothers had previously committed suicide.) His experiences as a village schoolmaster were at first a relief from his Weltschmerz, but within a couple of terms he had concluded that the local villagers were ‘loathsome worms’.

Then in 1922 his luck changed: his book was published in both Britain and Germany – though because of the work’s inherent unreadability he didn’t receive any royalty from sales. He continued working hard but unhappily in rural schools until his penchant for corporal punishment got the better of him, and when a young boy collapsed after a beating around the head. Wittgenstein disappeared the same day.

The architect

Following this crisis Wittgenstein tried to become a monk, but was rejected by the monastery because of his ‘unsound motives’, so he took work as a gardener, then threw himself into work on the design of a house for his sister Gretl. He also became mildly enamoured of a Viennese woman Marguerite Respinger, but his idea of love was of a sexless, platonic kind. Then gradually, via meetings with other Viennese philosophers, his original interests resurfaced, and he felt the need to return to Cambridge.

In 1919 he was forgiven and re-admitted as an Apostle; he registered as a PhD student, and worked with a supervisor who was seventeen years younger than him. He made new acquaintances (including the literary critic F.R. Leavis) continued ‘research’ which consisted largely of challenging his own previous ideas, and enjoyed watching westerns at the cinema with his non-philosophic friend Gilbert Pattisson. He was awarded a doctorate for his Tractatus, after a farcical viva in which he forgave his supervisors (Russell and Moore) for their inability to understand his work.

In 1930 he was awarded a five year fellowship on the strength of what was published after his death as Philosophic Remarks. This cleared him to abandon philosophic theory and start to concentrate on language. Many of his approaches and attitudes at this period chimed in rather unfortunately with the reactionary notions popularised by Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the Westwhich was influential around this time. This makes it less surprising that his next development was to look into the subject of magic and Frazer’s The Golden Bough (which T.S. Eliot had done some years previously) and it is even less surprising to realise that this led in its turn into outright anti-Semitism.

The apostate

Wittgenstein was very ambivalent about his racial heritage. His family were Jews who had largely converted to Christianity (Catholicism) but it was fairly clear that part of his anguished self-criticism sprung from an unwillingness to confront the truth of his origins (as in the case of his wealth and privilege) and the consequence of the self-hating and anti-Semitic Jew corresponds directly with the influence of Otto Weininger, whose reactionary opinions seem to run through Wittgenstein’s life like letters through a stick of rock.

Meanwhile he invited Marguerite, the woman he thought he was going to marry, for a three week holiday in Norway. He hardly saw her at all during that time, having also invited his friend Gilbert Pattisson. Not surprisingly, she decided he was not the marrying kind and left for Rome after two weeks. During this period Wittgenstein’s intellectual work proceeded in two directions: one was to undermine current notions of the philosophy of mathematics (he regarded maths as merely a technique for measurement) and the other was looking more and more closely into the roots of grammar, inventing for himself what he called ‘language games’.

At a personal level he became very close friends and eventually the lover of another young, clever, and very handsome undergraduate, Francis Skinner, someone who despite all his brilliance and promise, Wittgenstein eventually persuaded to give up academic life to work as a factory mechanic, which resulted in him becoming profoundly unhappy. Wittgenstein repeatedly urged the virtue of manual labour onto his students, whilst retaining his own position as a professional academic philosopher.

His teaching methods around this time were distinctly unorthodox. He gave up delivering lectures because they had become so popular. Instead, he dictated his ideas to a small group of favoured students, then let them circulate their notes amongst other students. This is the origin of what became known as The Blue and Brown Notebooks.

As his fellowship at Cambridge came towards its close, he faced another period of self-doubt and uncertainty. For a while there was a hare-brained scheme of going to work as a manual labourer in the Soviet Union – but that came to nothing, even after letters of introduction from the Russian ambassador in London. Instead, he retreated once again to living alone in Norway.

The confessions

However, from there he paid visits back home to Vienna and Cambridge to deliver a Tolstoyan ‘Confessions’ of his sins to friends and relatives. These turned out to be embarrassing revelations of trivial peccadillos and omissions of truthfulness which left most of his listeners mystified. What he doesn’t seem to have included is any mention of his homosexuality, which was subsumed under the heading of ‘sensuality’ in his diaries, along with detailed reports of his feelings of shame at masturbating.

In 1937, amidst Hitler’s manoeuvres to annex Austria, he was back in Vienna, missing Skinner but feeling at the same time that he should steer clear of ‘sensual temptations’. Instead he went to Dublin to investigate the possibility of a career in medicine. But following the Anschluss and his reclassification as a German Jew, he followed the advice of his friend and fellow philosopher Sraffa and obtained a job as research assistant at Cambridge and applied for British citizenship, which was granted in June 1939.

He moved in with Skinner and they lived together as a couple for the next two years. Wittgenstein was elected Professor of Philosophy and continued his lectures criticising what he saw as ‘scientific idol worship’. One of the students in his select audience who dared to take an opposing view was the young Alan Turing, who went on to develop his own philosophy of mathematics (in Manchester) to establish the foundations of modern computing.

When the war got under way two further events changed the direction of his life. First the sudden death of his lover Francis Skinner, and second his decision that he must give up teaching and take up some form of manual labour. He became a hospital porter at Guy’s Hospital in London. However, when his talents (and identity) were recognised, he was invited to join a medical research team based in Newcastle.

His next move was to Swansea where he had been given permission to continue his work in private. He continued with the philosophy of mathematics as his main concern, but began to include reflections on Freudian psychology and what he called ‘private language’. He arrived back in Cambridge in 1946 at the same time as his old tutor Bertrand Russell, who had been in America during the war. Both of them though the recent work of the other was worthless.

The living death

Following the end of the war, he was severely critical of the British government and its punitive attitude towards Germany, and he became rather sympathetic to the Left, though from a deeply conservative and an anti-science point of view. His antipathy to professional philosophy also deepened, and he regarded his own professorship as ‘an absurd …kind of living death’.

But as he wrestled with his pessimism and his plans to abandon philosophy (especially Cambridge) a glimmer of light came into his life. He fell in love with Ben Richards, a medical undergraduate almost forty years his junior. But to his existential worries was now added the issue raised by all such relationships – would it last? He answered this question for himself in characteristically perverse fashion by resigning from his post and going to live alone in a remote part of Ireland for the next year.

Once there, he thought he was losing the ability to do any constructive work, and the locals all thought he was mad. His only form of entertainment continued to be detective magazines and American ‘hard-boiled’ fiction. After a holiday in Vienna and Cambridge, he went to live in a hotel in Dublin, where he became a member of the Zoological Gardens in Phoenix Park. At first his work went well, but then he became ill and depressed, and despite uplifting visits from Ben Richards he began to feel that the end was drawing nearer.

In fact he had two years left to live, and he spent them living with friends in New York, Cambridge, and Oxford. He participated in philosophy seminars at Cornell University, but then became ill and felt he must return to Europe to die. Back in Cambridge he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He returned to live in the family palace in Vienna (where his sister was also dying) taking a great deal of trouble to conceal the nature of his disease from his relatives.

When the hormone treatment for his cancer brought about improvement, he moved back to Cambridge, despite all his continuing claims that he was disgusted by English culture. He undertook another holiday trip to Norway with Ben Richards, but his illness forced him back, where he moved into his doctor’s appropriately named house, ‘Storeys End’. The hormone treatment was stopped; he realised he was soon to die; and he put in a final creative burst for the last two months of his life, then died in April 1951 at the age of sixty-two.

Wittgenstein spent a great deal of his adult life in states of anguish, anxiety, and despair, even though he was very successful and became internationally famous. In this sense he was not unlike his fellow genius of the Hapsburg Empire and near contemporary, Franz Kafka, of whose works Wittgenstein remarked – ‘That man gives himself a great deal of trouble not writing about his trouble’ (though he could almost be speaking about himself). This apparent contradiction and perversity in Wittgenstein’s nature can perhaps be illuminated if not fully explained by a comparison with Leo Tolstoy.

Both Wittgenstein and Tolstoy came from extremely wealthy families with estates and retinues of servants; both felt guilty about the social privilege they enjoyed, and both ended up giving away their fortunes. Both of them adopted puritanical and Spartan lifestyles and became more or less vegetarian. Both of them felt driven by but enormously guilty about their sexual urges. In addition to this Wittgenstein was also homosexual, about which he would be forced to be secretive during the period he lived.

Both of them were obsessed with a religious belief in fundamental Christianity whose policies and practices they could not possibly maintain. Wittgenstein also knew that he was fundamentally Jewish, but tried to evade the fact. They were both intellectuals who railed against the intellectual establishment and preached the values of ‘the simple life’ and the moral dignity of manual labour – whilst keeping servants or being looked after by friends.

Both professed to yearn for a life in close proximity to simple peasants, but were appalled by the reality when they tried it. Both of them were misogynists; both of them affected workmen’s clothes; both were sceptical about scientific development, and both of them ended by repudiating their earlier works – Wittgenstein for intellectual reasons, Tolstoy for moral. This may not be a full explanation for his neuroses, but it suggests that they were not unique. Ray Monks’ magnificent biography is evasive on the issue of Wittgenstein’s homosexuality and it downplays the damaging effect of his peronality on the people who were attracted to him, but he presents a sufficiently comprehensive account of the life to enable us to make our own judgements on this very complex character.

© Roy Johnson 2015

Ray Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, London: Vintage Books, 1991, pp.654, ISBN: 0099883708

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on literary studies

More on the arts