Sylvia Beach (1887-1962) was an American-born bookshop owner and publisher who emigrated to Paris and became a central figure in the expatriate community between the first and second world wars. She is best known as the owner of the bookstore Shakespeare and Company and as the publisher of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses (1922).

She was born in Baltimore, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister and the grand-daughter of missionaries. At birth she was christened Nancy Woodbridge Beach, but she adopted the name Sylvia later. In 1901 the family moved to France when her father was appointed a minister at the American Church in Paris.

She spent the next few years living in Paris until the family moved back to America when her father became a minister in Princeton. However, she made return trips to France, then lived in Spain and later worked for the Red Cross in Serbia.

During the later years of the First World War she went back to Paris as a student of French literature. She had very little formal education, though by the time she finally settled in Paris in 1916 she could speak three foreign languages – French, Spanish, and Italian.

In 1917, at the age of thirty, she entered Adrienne Monnier’s bookshop, joined the lending library, and found the woman who became her lover and life partner. She also discovered her vocation and in 1919 opened her own bookshop as Shakespeare and Company in a nearby former laundry. The business functioned as both a bookshop and a lending library. Both women’s enterprises were financed by their parents.

“My loves were Adrienne Monnier and James Joyce and Shakespeare and Company”

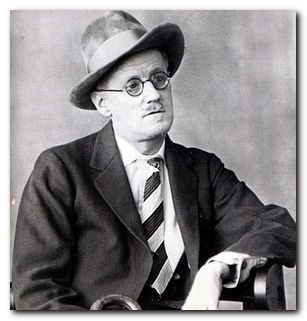

Primed with customers from Monnier who were interested in English literature, the new bookshop was an immediate success. One of her first loyal customers was Valery Larbaud who later became a translator of James Joyce’s work. Other early subscribers included Andre Gide, Eric Satie, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and Joyce himself. Sylvia Beach formed an immediate bond with Joyce, who was then in the middle of writing Ulysses.

As far as the business was concerned, she was astonishingly inefficient. She kept almost no records, and didn’t even put prices on the books she was trying to sell. Hours were spent chatting to people who just happened to have called by – but she was well liked for being so receptive.

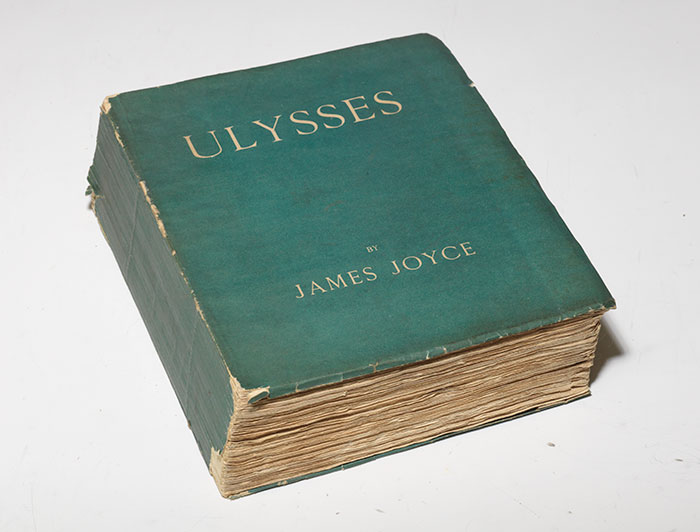

Beach took up the crusade on behalf of Joyce’s unpublished novel Ulysses when his principal benefactress Harriet Shaw Weaver failed to find people who would even set up the book in print.. It was considered ‘indecent’ by everyone – including Virginia Woolf.

When she decided to publish the novel herself she sent out publicity leaflets which had the interesting effect of attracting more American writers to visit her shop, eager for news of a work that was considered scandalous even before it was published. The visitors were also encouraged by a collapse of the Franc, which made living cheaper against the dollar.

Sylvia Beach poured all her time, money, and emotional resources into the production of Ulysses. Joyce sponged off her mercilessly – as he did off everyone else. The novel’s early years are now quite well known. It was vilified as ‘obscene’ and its author branded a ‘lunatic’. This only increased sales.

But not everyone was pleased. Gertrude Stein thought Shakespeare and Company was lowering the tone of the Left Bank by publishing indecent material. She also believed that the true genius of literary modernism was none other than her good self. She studiously avoided both Beach and Joyce at all cultural events.

Beach stayed out of these social squabbles and concentrated on the task in hand. She began a game of cat and mouse with the authorities who wished to supress Joyce’s work. Copies of Ulysses were smuggled to America and England, and occasionally the customs officers would confiscate her parcels and destroy their contents. [My ‘old’ copy of the Bodley Head edition has this shameful record of prurient vandalism reproduced as a preface.]

She befriended more Americans in the next wave of expatriates – writer Ernest Hemingway and composers George Antheil and Aaron Copeland. In 1926 she brought out a fourth edition of Ulysses, which was printed with copies of revisions and corrections to the original text. Meanwhile Joyce had begun work on his next book Finnegans Wake which was to take him seventeen years to complete.

The cross-cultural fertilizations that took place in this period are well illustrated in the figure of John Dos Passos. He was a visitor to Sylvia Beach’s bookshop at the time he was writing Manhattan Transfer. He was naturally influenced by Ulysses, but he also met Soviet cinematographer Sergei Eisenstein with whom he discussed the techniques of collage, fast-cut editing, and montage, all of which he incorporated into his literary style.

There was a small cloud on this endlessly sunny horizon when Ford Maddox Ford threatened to open a rival bookshop offering lower prices. Sylvia simply removed all his works from her own shop, his sales dropped, and his plans collapsed.

Whilst the fast sets of the Hemingways and the Scott Fitzgeralds passed their summers in month-long parties in Pamplona and Antibes, Sylvia and Adrienne retreated to an isolated farm in the Savoy mountains, living on fresh milk and sleeping in a hayloft.

By 1926 the American influence on Paris was in full spate. Josephine Baker was a succes de scandale in Le Revue Negre. Beach made her contributions to this fashion by organising a Walt Whitman exhibition and helping to promote the sensational performance of George Antheil’s Ballet Mechanique that ended in a riot.

But the American connection was not all sweetness and light. Samuel Roth, a notorious publisher in New York, brought out a pirated copy of Ulysses. The novel was not protected by copyright at this time because America had not signed the Bern agreement.

Sylvia Beach orchestrated an international protest, and meanwhile supported Joyce through gritted teeth when extracts from Work in Progress (which became Finnegans Wake) began to appear, much to general bewilderment. Harriet Weaver, his principal benefactress predicted that it would eventually become a ‘curiosity of literature’. History might prove her right.

In 1927 Beach’s mother was arrested in Paris on a charge of shoplifting in Galleries Lafayette. Rather than face the public humiliation of a trial, she committed suicide. Sylvia was devastated and, exhausted by her efforts to fight the Roth piracy, she put a little more distance between herself and Joyce.

Around this time Samuel Beckett appeared and was added to the roster of unpaid ‘assistants’ to Joyce, who continued to cadge, borrow, and even steal money from anybody who had any.

This decade of license and excess – ‘The Roaring Twenties’ – came to an abrupt halt in October 1929 with the Wall Street crash. But not everyone suffered: Joyce continued to fund his lavish lifestyle with other people’s money and started the new age of austerity by biting the hand that had fed him for the previous ten years. He cheated Sylvia Beach out of the rights to Ulysses which she had gone to so much trouble to publish for him.

Yet with the burden of Ulysses removed, her financial position at the shop at first actually improved. But on the other hand, many of her expatriate American customers began returning to their homeland. The value of the dollar was falling, and European stormclouds were gathering. She was forced to sell off some of her precious first editions and manuscripts, and a ‘friends of Shakespeare and Company’ fund was established to keep the shop alive.

In 1936 Beach paid her first visit to America for twenty-two years. On return to Paris she found that a rival had moved in to live with her lover Adrienne. The political uncertainties of the late thirties were no good at all for business, and she only kept the shop going thanks to generous gifts from friends and a series of sponsored internships.

At the outbreak of war and the occupation of Paris by the Germans, Sylvia opted to stay put and keep the shop open. But when a Nazi officer threatened to close the business because she would not sell him a copy of Finnegans Wake, she hid her entire stock in an attic at the top of the building, where it remained throughout the war.

She was arrested in 1942 and interned at Vitell, later to be released following the influence of a friend in Vichy. At the liberation in 1944 she did not, contrary to popular myth, re-open the shop after it was ‘liberated’ by Ernest Hemingway. Instead, she organised help for her friends and began to write her memoirs.

Adrienne, her mentor, mother-figure, and lover committed suicide in 1955 to escape the double pains of rheumatism and Menieres disease. Beach lived on to establish a permanent home for her archive of Joyce materials at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and she died in her beloved Paris in 1962.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Noel Riley Fitch, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties, London: Penguin, 1985, pp. 447, ISBN:

More on biography

More on literary studies

More on the arts