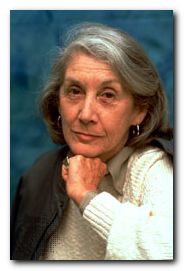

Nadine Gordimer (1923—2014) was born into a privileged white middle-class family in the Transvaal, South Africa. She began reading at an early age, and published her first story in a magazine when she was only fifteen. Her wide reading informed her about the world on the other side of apartheid – the official South African policy of racial segregation – and that discovery in time developed into strong political opposition to apartheid. She attended the University of Witwatersrand for one year. Her first book was a collection of short stories, The Soft Voice of the Serpent (1952). In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. She was awarded the Nobel prize for Literature in 1991.

Nadine Gordimer (1923—2014) was born into a privileged white middle-class family in the Transvaal, South Africa. She began reading at an early age, and published her first story in a magazine when she was only fifteen. Her wide reading informed her about the world on the other side of apartheid – the official South African policy of racial segregation – and that discovery in time developed into strong political opposition to apartheid. She attended the University of Witwatersrand for one year. Her first book was a collection of short stories, The Soft Voice of the Serpent (1952). In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. She was awarded the Nobel prize for Literature in 1991.

Nadine Gordimer was a writer who started by picking up the modernist baton from authors such as Virginia Woolf, and she is one of the few writers who has taken the techniques of modernism a few steps further. She does this particularly in her short stories, where like Woolf she uses the genre as an experimental kitchen for her longer prose works such as her novellas and full length novels. In fact some of her shorter fiction is more interesting in terms of formal experimentation than her novels, many of which are often rather long and formless – although this is a purely personal opinion.

Her writing is always interesting politically – and she never shirked the difficult issues raised by the legacy of white European domination in South Africa. She’s also an excellent observer of what might be called the politics of gender or sexuality. She writes about the physical relationships between women and men in a way which is honest, frank, revealing, and unsparingly unsentimental.

Some passages in her work render the sexual tensions between men and women more accurately than any writer since D.H.Lawrence – and they have the novelty of often being presented from a woman’s point of view, though she is perfectly capable of writing from a male perspective too. She’s also very good at dealing with issues of sex at the level of furtive assignations and sweaty armpits – something often ignored by serious writers.

Her most experimental work is in some of the short stories; the longer stories and novellas such as July’s Children are nearly as successful, but her novels have not seemed so tightly controlled – with one magnificent exception. The Conservationist which lays bare the whole issue of the white European in black Africa.

The Conservationist (1974) concerns a white industrialist who farms his land (with native help) at the weekend and genuinely wants to make his presence a positive contribution. But most of all he wants to preserve his power and his privileged way of life – despite being surrounded by poverty and suffering. He just doesn’t understand that the indigenous population are the natural owners of the land, and the result is disastrous – for him.

The Conservationist (1974) concerns a white industrialist who farms his land (with native help) at the weekend and genuinely wants to make his presence a positive contribution. But most of all he wants to preserve his power and his privileged way of life – despite being surrounded by poverty and suffering. He just doesn’t understand that the indigenous population are the natural owners of the land, and the result is disastrous – for him.

It’s a marvellous novel which summarises the situation in South Africa in the 1980s – but in a way which casts a shadow right up to the present day. The other issue which this magnificent book conveys is the sense of place which is so important to life in South Africa. The native Africans are dispossessed – yet they are at one with the land. Immigrant landowners might try their best to ‘own’ and ‘cultivate’ the land, but they are never ‘at home’ on it.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Jump Her development as a writer of short stories is wonderful. She starts off in modern post-Checkhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, Nadine Gordimer experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative (rather like Virginia Woolf) and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred.

Jump Her development as a writer of short stories is wonderful. She starts off in modern post-Checkhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, Nadine Gordimer experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative (rather like Virginia Woolf) and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Selected Stories As her work matured, her style and methods underwent a similar development to those of Virginia Woolf. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. There are some stories which make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes on first reading it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

Selected Stories As her work matured, her style and methods underwent a similar development to those of Virginia Woolf. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. There are some stories which make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes on first reading it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The following extract from The Conservationist gives some idea of her robust prose style, composed of dense, powerful imagery, rich vocabularly, gnarled syntax, and sinuous prose rhythms.

The weather came from the Mozambique Channel.

Space is conceived as trackless but there are beats about the world frequented by cyclones given female names. One of these beats crosses the Indian Ocean by way of the islands of the Seychelles, Madagascar, and the Mascarenes. The great island of Madagascar forms one side of the Channel and shields a long stretch of the east coast of Africa, which forms the other, from the open Indian Ocean. A cyclone paused somewhere miles out to sea, miles up in the atmosphere, its vast hesitation raising a draught of tidal waves, wavering first towards one side of the island then over the mountains to the other, darkening the thousand up-turned mirrors of the rice paddies and finally taking off again with a sweep that shed, monstrous cosmic peacock, gross pailletes of hail, a dross of battering rain, and all the smashed flying detritus of uprooted trees, tin roofs, and dead beasts caught up in it.

© Roy Johnson 2009

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield