Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) was a surrealist painter and writer whose life spanned two centuries and two continents. She was born in Chorley, Lancashire to wealthy parents in textile manufacturing.

Educated by private tutors and nuns, she was a rebellious and disobedient child who was expelled from more than one school. Her father disapproved of her interest in art, but her mother encouraged her cultural ambitions.

As the daughter of an upper-class family she was expected to be a debutante, and was actually presented formally at the court of King George V. But when she continued to rebel, she was sent to study art in Florence, where she was impressed by medieval painting and architecture. On return to London she was enrolled at the Chelsea School of Art and then at the academy run by expatriate cubist painter Amedee Ozenfant.

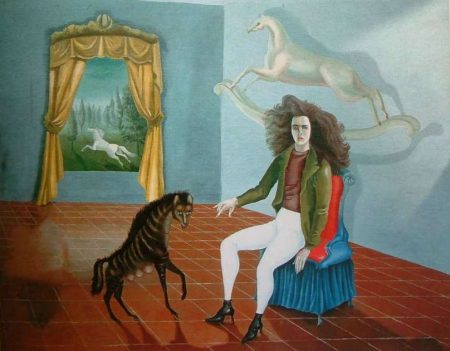

The year 1936 was something of an annus mirabilis for the nineteen year old student. She attended the International Exhibition of Surrealism at the New Burlington Galleries, and she read Herbert Read’s influential book Surrealism. She was attracted to the blend of realism and fantasy that the new artistic movement promoted. It also allowed her to blend the human with the animal world which is one of the striking features of her work.

Shortly afterwards she met Max Ernst, the German-born leader of both the Dadaism and Surrealism movements. He was forty-seven and married, she was twenty and single. They fell in love immediately, and the following year he dissolved his marriage and took her to Paris. He introduced her to other surrealist artists such as Joan Miro and Andre Breton. Their shared interests were reflected by the presence of birds and animals in their work.

Following this they moved to a small town in the Ardeche region of southern France, where they supported each other in painting and sculpture. She also experimented with automatic writing, which at that time was an integral part of surrealism. It was thought possible to tap into the unconscious mind by removing the critical, censoring element from the process of composition.

However, tragedy struck their idyll with the outbreak of war. Ernst was arrested by the French government for being a ‘hostile alien’. He was later released following the intercession of friends. But when the Germans occupied France, he was arrested again, this time by the Gestapo who had him on their list of ‘degenerate artists’. He managed to escape to America with the help of Varian Fry and Peggy Guggenheim, whom he later married.

Leonora was devastated by the separation. She was forced to sell everything in France and escaped to Spain, where she suffered from paralysing anxiety attacks and delusional episodes. She was eventually hospitalised and subjected to the barbaric ‘convulsive therapy’ and anti-psychotic drug treatment that was thought necessary at that time for people with mental disorders. She was traumatised by this experience, and eventually sought refuge in the Mexican embassy in Lisbon. The whole of this ghastly period is recorded in her memoir Down Below.

She made the experience of all this distress the source of inspiration for many of her works – both in fiction and graphic art. This was not unlike her contemporary the artist Frieda Kahlo. In 1941 she married the Mexican diplomat Renato Leduc whom she had met at the embassy. Like many marriages contracted around that time, it was one of convenience, enabling them to escape Europe. They went to New York, travelled down to Mexico, and divorced two years later. She remained in Mexico City for the rest of her life.

Her life was one of domestic seclusion – although she did become something of a cultural celebrity in the capital city. She met the Franco-Russian writer Victor Serge who was also living there in exile at the time. Later she married the Hungarian photographer Emeric Weisz with whom she had two sons, Pablo and Gabriel.

In the 1940s and 1950s her work became an interesting blend of her own fantasy and surrealism, Mexican folk lore and myth, and a growing sense of what we would now call ‘women’s liberation’. She wanted to explore the relationship of women’s bodies and sexuality with their psychological experiences of erotic life, of motherhood, and of domesticity.

She was completely unknown in Europe at that time, and remained so until she was ‘discovered’ in the early twenty-first century. But she exhibited in Mexico and had a certain following in New York. She had a close relationship with the Spanish surrealist painter Remedios Varo, who also lived in Mexican exile in the same neighbourhood. They even wrote collaboratively and attended meetings held by the Russian occultists Ouspensky and Gurdjieff.

In the 1960s she collaborated with other members of the Latin-American avant-garde such as the writer Octavio Paz and the film maker Luis Bunuel. She was also honoured with a major retrospective at the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. During the latter decades of her life she turned increasingly to three-dimensional works, producing bronze sculptures of humans and animals, as well as figures that combined both. She died in Mexico City in 2011 at the age of ninety-four. Her house in the Roma district has since been turned into a museum.

© Roy Johnson 2018

The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington – biography – Amazon UK

The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington – biography – Amazon US

Down Below – Memoir – Amazon UK

Down Below – Memoir – Amazon US

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington – Amazon UK

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington – Amazon US

More on biography

More on literary studies

More on the arts