tutorial, commentary, web links, and study resources

The Diary of a Man of Fifty first appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine and Macmillan’s Magazine for July 1879. The first English book version appeared later the same year in the collection The Madonna of the Future and Other Tales published by Macmillan.

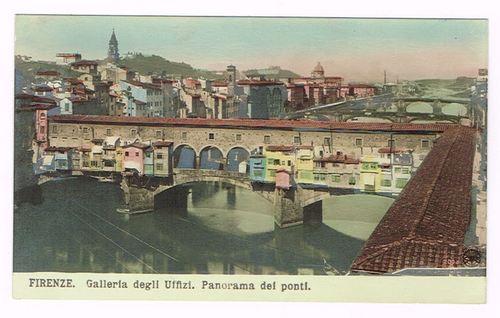

The setting – Florence

The Diary of a Man of Fifty – critical commentary

This tale is one of James’ least-known stories, and he didn’t even include it in the twenty-four volume New York Edition of his Novels and Tales (1907-09). It’s also rather unusual, because it’s written in the form of a journal. James normally liked to keep the narrative and the point of view tightly under his own control in the form of a first person or omniscient third person narrator. The only other instances of his using the diary and journal forms in his tales were A Landscape Painter (1866), A Light Man (1869), and The Impressions of a Cousin (1883).

The General is very forcibly struck by the parallels between his own situation and Stanmer’s. The General was in love with the beautiful Countess twenty-five years previously, and now he meets young Stanmer who is enchanted by her equally alluring daughter, and who bears the same name – Bianca. The General felt betrayed by the Countess when she married his rival, Count Camerino, and he feels that Stanmer is likely to be ill-treated by Bianca in the same way – though he has no evidence to support this notion.

Stanmer feels that the General is pursuing the ‘analogy’ too far, and resists the attempts to persuade him of any danger. And in the end, Stanmer does marry Bianca, and he is happy according to his own report. So for once in these cautionary tales about the dangers of marriage, the protagonist’s fears seem to be overturned. The General is left wondering what might have been, and the reader is left wondering if he is another candidate for James’s collection of unreliable narrators – a man who is so blinded by his own past experience and lack of real perception that he is unable to correctly interpret the world he inhabits.

It is difficult to form a clear judgement on this issue – because we do not have sufficient independent evidence. But it is worth noting (in the balance of its being a ‘cautionary tale’) that both the Countess and her daughter Bianca ‘lose’ three husbands between them – all of whom die in duels brought about because of rivalry and jealousy. So no matter what we think in the choice between Stanmer and the General, the state of matrimony is depicted as a zone of conflict and potential death.

Study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1874—1884 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Diary of a Man of Fifty – Classic Reprint edition

The Diary of a Man of Fifty – Classic Reprint edition

![]() The Diary of a Man of Fifty – Kindle edition

The Diary of a Man of Fifty – Kindle edition

![]() Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition

Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition

![]() The Diary of a Man of Fifty – eBook formats at Gutenberg

The Diary of a Man of Fifty – eBook formats at Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Diary of a Man of Fifty – plot summary

An English army general of fifty-two returns to Florence twenty-five years after a romance with Countess Falvi, a woman who has died ten years previously. He revisits the places they used to frequent together.

He then meets Edmund Stanmer, a young English traveller of twenty-five who is acquainted with the Countess’s daughter Bianca. The General takes a liking to him, feeling that he is a reminder of his younger self.

Stanmer arranges a meeting between Bianca and the General, who is at first reluctant to follow it through, because his memories of her mother are that she was a dangerous woman.

However, when he goes to see Bianca the next day she is charming and attractive. They reminisce about her mother. Bianca lost her own father when she was young; her mother re-married, and she also lost her own husband three years previously.

The following day the General warns Stanmer that Bianca is an actress and a coquette, just like her mother. Stanmer resents the comparison and wants to know what the mother did to hurt the general – but he initially passes up on the opportunity to hear what it was.

Next evening at the Casa Salvi the General learns that Bianca’s stepfather was killed in a duel. They discuss Stanmer together , and Bianca asks the general to ‘explain’ her to his young friend.

The General continues to warn Stanmer about Bianca, but admits that he finds her fascinating. He then stays away from the Casa Salvi for a while, uncertain about his intentions regarding Stanmer.

But then Stanmer demands to know what happened between the General and the countess. The General reveals that he was jealous of Count Camerino, who was a suitor to the Countess, and who killed her husband in a duel caused by jealous rivalry – though another man (acting as his second) was deemed responsible. The General was horrified when the Countess married the man who had killed her own husband, and he left Florence, never to see her again.

The General takes his leave of Bianca, who reproaches him for having deserted her mother at a time when she needed a protector.

The general later hears that Stanmer married Bianca. The two men meet again in London some time later, where Stanmer tells the General that he was wrong about his account of the Countess, and that maybe she really did need his protection. This causes the general to doubt his own judgement, and he thinks it might be possible that he has made a mistake.

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Principal characters

| General — | an un-named former soldier from the English army in India (52) |

| Edmund Stanmer | a young Englishman (25) |

| Countess Salvi-Scarabelli | the General’s former amorata |

| Bianca Scarabelli | her beautiful daughter |

| Count Salvi | the Countess’s former jealous husband |

| Count Camerino | the general’s rival, and second husband to the Countess |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2005

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories