tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Princess Casamassima first appeared as monthly serial insallments in The Atlantic Monthly magazine between 1885 and 1886. It was published in book form as three volumes by Macmillan in 1886. The work is very unusual in James’s oeuvre in dealing with both the working classes and with revolutionary politics. It also features a character (the Princess) who had appeared as the American beauty Christina Light in Roderick Hudson, published ten years previously in 1875.

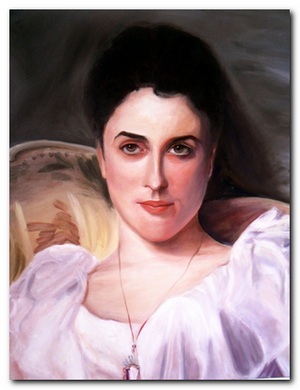

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

The Princess Casamassima – critical commentary

The serial novel

Like most other nineteenth century novelists, James was accustomed to producing his novels first in the form of monthly magazine installments, then in book form – either as single or multiple volumes. The Princess Casamassima first appeared in The Atlantic Monthly over the space of a year in fourteen installments, then in three volumes, published by Macmillan in 1886.

It has to be said that one reason why the novel has not proved popular with general readers (or scholars) is that the pace of the narrative is glacially slow. Although there are sufficient characters and plot intrigue to provide psychological development and dramatic tension, much of the story is laboured beyond belief. It’s as if James felt uncomfortable with the subject he had chosen. It is also true that he was literally making up the story as he went along, having been held up in his writing schedule over problems with his previous novel The Bostonians which was published almost at the same time (1885-1886).

There is none of the light and shade or the dramatic tension one would expect in the serial form (as one gets to abundance in Dickens for instance). Journeys from one location to another are described in excessive detail; interaction between the characters is traced exhaustively, but does not lead anywhere (see below); and there is a great deal of repetition.

Politics

Conversely, many elements hinted at in the account of events, particularly related to the ostensible subject of social revolutionaries, are not actually realised. There are mentions of spies, informers, agents provocateur, hard-line anarchists, and police surveillance, but none of this is dramatised or even discussed by the principal characters.

One cannot expect James to be particularly well informed on matters of revolutionary politics, because very few people knew anything much about the subject at that time in the 1880s. It was generally assumed that revolutionaries were small, almost secret groups of bomb-throwing anarchists and desperadoes who had utopian dreams of dispossessing the rich and overturning society.

However, James did choose his subject consciously, so he must be held accountable for his failure to provide any knowledge of its workings. None of the meetings in the Sun and Moon are reported, and even the conversations of his two principal characters, Hyacinth and Paul, do not cover revolutionary politics or even social theory. Paul merely opines that ‘the democracy’ will eventually prevail, whilst Hyacinth volunteers for his fatal mission as an act of bravado.

However, James was not entirely unaware of the lives of lower-class people. His story In the Cage deals with the life and working conditions of a young woman who operates a telegraphy machine within a grocery store in London’s West End.

The Dickensian shadow

There are many elements of the novel that have powerful overtones of Dickens. For instance, Hyacinth’s melodramatic origins. He is the unrecognised bastard child of a French prostitute and an English Lord who has been raised by an impoverished dressmaker. His mother has murdered his father; and as a child Hyacinth is taken to a gruesome deathbed meeting with his mother in a prison.

Rosy Muniment, the irrepressibly cheerful invalid with a crippled spine who finds positives in everything that surrounds her is closely reminiscent of Fanny Cleaver (Jenny Wren) the doll’s dressmaker in Our Mutual Friend whose lament is “my back’s bad and my legs are so queer” and is unstoppably chirpy and optimistic, despite her disabilities.

Mr Vetch and Hyacinth are a very close parallel to Pip and Joe Gargery in Great Expectations. Mr Vetch does everything to protect and help Hyacinth get on in life, and is very loyal to his foster mother. When Hyacinth becomes involved with the aristocracy and develops snobbish and selfish values, Mr Vetch is uncomplaining and does not reproach an entirely unthankful protege – and even offers to lend him money from his hard-earned savings as Hyacinth is engaged in squandering his small inheritance on trips to Paris and Venice.

There is even direct reference to Dickens when Paul Muniment sees someone who reminds him of Mr Micawber.

Resolution

What reinforces this impression of torpor more than anything else is the fact that at the end of the novel there are so many unfinished or unresolved elements in the plot. We know that Hyacinth cannot contain the contradiction which exists within him – the pull between his love of ‘civilization’, luxury, plus an aristocratic lifestyle, and his fast-disappearing socialist sympathies. So he resolves the issue personally by shooting himself. But what happens to the other ‘revolutionaries’? We have no idea what happens to the Princess, to Paul Muniment, to Eustace Poupin, to Schinkel, or even to Hoffendahl’s plot to assassinate someone of importance.

Many of the other plot lines are also left in an unfinished or unresolved state. The relationship between Paul and Hyacinth is not brought to any closure – nor is Paul’s romantic dalliance with the Princess. We do not have any explanation for Mr Vetch’s unquestioning support for Hyacinth, even when he is betraying his own principles and drifting into a self-indulgent ‘appreciation’ of luxuries afforded to the upper class.

Even Hyacinth’s melodramatic origins are not resolved or examined in any way in the later parts of the novel. Where Dickens might have produced some sort of long-term dramatic connection resulting from this sexual link between upper and lower class, James leaves this whole melodramatic episode merely as a donnée to illuminate Hyacinth’s problematic origins. In a novel of this length and complexity, I think readers are entitled to expect resolutions or at least connections to be made between the various elements of the narrative. All we are given instead is a ‘surprise’ twist to the tale which is fairly easy to foresee and brings one of James’s longest novels to an abrupt and quite unsatisfactory stop.

The Princess Casamassima – Study resources

![]() The Princess Casamassima – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Princess Casamassima – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Princess Casamassima – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Princess Casamassima – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Princess Casamassima – Digireads – Amazon UK

The Princess Casamassima – Digireads – Amazon UK

![]() The Princess Casamassima – Digireads – Amazon US

The Princess Casamassima – Digireads – Amazon US

![]() The Princess Casamassima – Library of America – Amazon UK

The Princess Casamassima – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() The Princess Casamassima – Library of America – Amazon US

The Princess Casamassima – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Princess Casamassima – plot synopsis

Book First

Chapter I. Prison office Mrs Bowerbank visits poor dressmaker Miss Amanda Pynsent (‘Pinnie’) regarding a possible visit for her adopted son Hyacinth Robinson to see his mother, who is dying in prison where she has been confined for the previous nine years for murdering he lover Lord Frederick Purvis, who is Hyacinth’s father.

Chapter II. Pinnie seeks advice from her radical neighbour Theophilious Vetch. She worries about revealing to Hyacinth his true parentage. Mr Vetch takes a tough realistic view and thinks Hyacinth ought to know the truth.

Chapter III. Pinnie and Hyacinth visit the gloomy penitentiary, but the meeting between Hyacinth and his mother is a disaster. He does not like the prison and does not know why he is there. His mother thinks he hates her. He submits unwillingly to her brief embrace, then they leave

Chapter IV. Ten years later Pinnie receives a visit from Millicent Henning, Hyacinth’s childhood friend and the daughter of a dissolute neighbouring family who have been evicted. Millicent is now a pushy and vulgar young cockney woman. Pinnie thinks she made a grave mistake in taking Hyacinth to the prison; her business has declined, and she has fallen onto hard times.

Chapter V. Hyacinth arrives home. He has become a bookbinder, has taught himself French, and although physically slight is attractive. But he is bitterly conscious of his low status in life. He is attracted to Millicent and walks home with her. She asks him about his ‘family background’ and mocks his lowly status. Nevertheless, he arranges to see her again.

Chapter VI. In a narrative flashback, when Mr Vetch has a copy of Bacon’s Essays bound as a gift for Hyacinth, he meets French radical exile Eustace Poupin, whereupon the two families become weekend friends. Poupin finds a position for Hyacinth at the Soho bindery where he works and becomes his mentor.

Chapter VII. Under the influence of Poupin, Hyacinth tries to understand social class and the revolutionary ethos. Via meetings of radical sympathisers in the back room of the Sun and Moon pub in Bloomsbury, he meets Paul Muniment, who takes him home to meet his disabled sister Rosy, where they also meet Lady Aurora Langrish, an aristocratic do-gooder.

Chapter VIII. They discuss various degrees of radical ideas, ending with predictions on how the aristocracy might behave in the event of an uprising amongst the lower classes in England.

Chapter IX. Rosy recounts to Hyacinth the history of their relationship with Lady Aurora, the upper-class ‘saint’ who spends her time amongst the poor. Hyacinth is very impressed by Rosy as she recounts her family’s poor working-class background. She supports the oppressed but wants the aristocracy preserved. Hyacinth wants to know more about the ‘party of action’ from his friends, but Paul keeps him at arm’s length in a good-humoured way.

Chapter X. Some months later Pinnie is more than ever concerned about Hyacinth’s continuing relationship with Millicent. He sees the positive side of her vulgar plebeian nature, and seems unaware of any sexual attraction he might be feeling for her. He even visualises her in heroic fashion as Liberty leading the people at the barricades.

Chapter XI. Hyacinth continues his relationship with Millicent, despite her having no taste in anything beyond vulgar acquisitiveness. He meanwhile feels excluded from the aristocratic lifestyle to which he instinctively feels he has the right. This produces a dichotomy in his political allegiances which he cannot resolve. He eventually unearths the true story of his origins. He asks Mr Vetch to secure tickets for a show and is asked about his membership of the First International.

Book Second

Chapter XII. When Hyacinth takes Millicent to the theatre he meets Captain Sholto (an upper class fellow radical) who wants to introduce him to his friend the Princess Casamassima. Hyacinth is torn between feeling patronised and flattered.

Chapter XIII. When he joins the Princess and Madame Grandoni in their box he is overwhelmed by their aristocratic glamour. The Princess reveals that she sends Sholto out into society to bring her ‘interesting’ people to study. She wants to ‘understand’ the common people and believes that social revolution is bound to be imminent.

Chapter XIV. When Hyacinth reports these events to Paul, his friend refuses to trust or give any of his time to people he sees as his class enemies. He makes an exception for Lady Aurora because she makes a practical effort to help Rosy. Hyacinth takes Pinnie to see Rosy, who ‘commissions’ her to make a pink nightgown.

Chapter XV. Hyacinth compare political notes with Lady Aurora. She reveals her deep-seated antipathy to her own class and the effort it has cost her to break free of it. Paul arrives with Captain Sholto and reveals to Hyacinth that Sholto is merely a tout for the Princess, who he regards as a ‘monster’. Sholto then invites Hyacinth back to his rooms in Westminster where they discuss the Princess, who was expelled from her home by her husband, who now wants her back again.

Chapter XVI. Prince Casamassima arrives in London hoping to effect a reconciliation with his wife – but she refuses to see him. The Prince discusses the situation with Madame Grandoni, fearful that Christina will bring his illustrious name into disrepute. Hyacinth arrives, and Madame Grandoni warns him against his radical ideas and principles.

Chapter XVII. When the Prince arrives, the Princess first complains about her husband, then she asks Hyacinth to help her ‘know the people’. She outlines her own life history and how she despises the emptiness of the aristocracy. Finally she invites him to visit her in the country. Hyacinth binds a copy of Tennyson’s poems in her honour, but when he goes to deliver it she has left town.

Chapter XVIII. Madame Grandoni meets the Prince before leaving for the country. She explains that Princess Christina now thinks it was a mistake to marry for money and a title. She also realises that Christina now finds the Prince terminally boring. The prince quizzes her about Hyacinth and Sholto.

Chapter XIX. Pinnie uses the creation of the pink dressing gown as an excuse to cultivate Lady Aurora. Hyacinth finally calls on Lady Aurora to collect the French books she has promised to lend him. He is slightly amused that she wishes to explore ‘pauperism’, and she reveals that she thinks Captain Sholto is vulgar.

Chapter XX. Hyacinth is conscious of a double connection with the upper class – the Princess with whom he is a little in love, and Lady Aurora who he regards as a ‘saint’. He bumps into Sholto in a pub, and together they meet Millicent, with whom he has a lover’s tiff. Sholto takes them to a music hall, and Hyacinth wonders if there is a secret liaison between Sholto and Millicent.

Chapter XXI. Paul Muniment and Hyacinth are regarded as natural leaders amongst the radicals at the Sun and Moon in Bloomsbury. Paul is sceptical and taciturn, whilst Hyacinth is admired because of his mother’s tragic history. Hoffendahl, a famous German revolutionary is visiting London. He has been imprisoned and tortured, but has refused to name names. The local conspirators debate the ethics and the practical strategies of personal sacrifice. Hyacinth wonders why Paul does not take him more into his confidence. When a provocateur accuses them of cowardice, Hyacinth makes a defiant speech. Then Paul invites him and two others to meet Hoffendahl.

Book Third

Chapter XXII. Three months later Hyacinth visits Medley, the Princess’s rented estate in the country, and is impressed by its age and beauty. The Princess treats him lavishly, but he is conscious of the contradiction of her claiming to be concerned for the poor whilst living in a house with forty to fifty rooms. He has previously pledged himself to the revolutionary cause of Hoffendahl. When he mentions Lady Aurora, the Princess regrets that she is not the first titled lady he has known.

Chapter XXIII. After lunch Hyacinth goes for a drive with the Princess and Madame Grandoni, then at high tea more visitors arrive. The Princess puts pressure on him to stay. He explains that he needs to go back to work the next day, but she flatters him and persuades him to stay on.

Chapter XXIV. Next day the Princess quizzes him about his activities. He tells her he has pledged his life when it becomes necessary to act. The people at the Sun and Moon he now regards as inconsequential. He has been sold a vision of an international network of revolution about to be ignited. He claims to be cautious, but names everyone involved.The Princess reveals that she too knows Hoffendahl but has been kept at arm’s length because he doesn’t trust women. The Princess flatters Hyacinth, and he reveals his origins to her.

Chapter XXV. A few days later Hyacinth meets Captain Sholto with whom he has been in rivalry regarding Millicent. Sholto reveals that he doesn’t believe in the revolutionary cause at all, and is only interested in regaining his place close to the Princess, to whose every whim he panders.

Chapter XXVI. The Princess invites Sholto to say at Medley. He believes that Hyacinth will suffer at the hands of the Princess. Hyacinth realises that Sholto is an empty shell who fabricates the role of slave to the Princess because he has nothing else to do. The Princess is bored by his attentions, but tolerates him.

Chapter XXVII. Hyacinth returns home from Medley to discover that Pinnie is dying, attended by the devoted Lady Aurora. He thinks that people by now might know the ‘secret’ of his birth, but he is no longer concerned. He becomes painfully aware of the sordid living quarters in which he has been raised. Mr Vetch explains that Pinnie wanted Hyacinth left undisturbed whilst he enjoyed his high social connections. He offers Hyacinth money and takes an unquestioning fatherly interest in him.

Chapter XXVIII. Hyacinth tries to look after the dying Pinnie, who is pleased that he has made contact with the aristocracy. But she dies, leaving him all her meagre savings. Mr Vetch continues to be supportive, and Hyacinth realises that he owes him and Pinnie a debt of looking after them – and that this will not be possible if he should end up in jail. Pinnie has expressed the hope that Hyacinth would travel abroad – to Paris.

Book Fourth

Chapter XXIX. Following his inheritance and a further advance from Mr Vetch, Hyacinth visits Paris and thinks about his mother’s father, the revolutionary watch-maker who died on the barricades. He is seduced by the glamour and the luxury of the centre of modern civilization and feels distant from his socialist allegiances. He thinks he has an unbreakable bond to the Princess and yet still feels tied to Millicent.

Chapter XXX. Hyacinth continues to feel a slightly ambiguous admiration for his friend Paul Muniment. After Paris he travels to Venice, from where he writes to the Princess confessing his change of heart regarding the revolution. He now values the products of civilization too much to think of destroying them.

Chapter XXXI. When he returns to London, he finds that the Princess has gone. Feeling that he has spent his inheritance on an experience he wishes to share with her, he worries that she might have changed. He goes back to work reluctantly and begins to have literary aspirations. Mr Vetch supports him as ever, and he begins to feel distant from his fellow workers.

Chapter XXXII. When Hyacinth visits the Muniments, he finds the Princess there with Lady Aurora. She claims to have given up all her worldly goods, selling off everything to give to the poor. It is her idea of making a grand sacrifice.

Chapter XXXIII. Hyacinth walks with the Princess back to her small rented house in Paddington. She protests poverty but seems to have retained servants. Hyacinth thinks this is a fad which will rapidly fade away. She also claims that she admires Paul Muniment for not coming to visit her.

Chapter XXXIV. Hyacinth discusses the Princess with Lady Aurora, who is a great fan. They all meet for tea together in POaddington. The Princess offers to help Lady Aurora in her ‘work’ – albeit in a patronising manner. Nevertheless, the two aristocratic women seem to form a close relationship.

Chapter XXXV. Paul and Hyacinth one Sunday travel out to Greenwich, where Hyacinth asks Paul if he is in love with the Princess. Paul is evasive in reply, and they speak instead of Hyacinth’s ‘contract with Hoffendahl. Paul thinks it might not happen; the issue tests their friendship; and Paul jokingly calls Hyacinth a ‘duke in disguise’. Paul does not believe in ‘the millennium’ (violent revolution) but in ‘the democracy’.

Chapter XXXVI. Paul visits the Princess. She claims she wishes to help the ’cause’ and offers to replace Hyacinth in his contract with Hoffendahl. She also offers money, but Paul remains distant and sceptical, because he does not trust women.

Chapter XXXVII. The Princess receives Mr Vetch as a visitor. He finds it very difficult to say why he has come, except that it relates to Hyacinth. He wants Hyacinth to reconcile himself to society, and believes he no longer has such radical beliefs as previously. He believes that Hyacinth has fallen in with dangerous conspirators and is about to perform some sort of rash act. The Princess denies all knowledge of any such pledge. Mr Vetch feels responsible, because he introduced Hyacinth to the revolutionaries via Poupin. He also wishes to check with Paul Muniment, but the Princess appeals to him to leave Paul alone.

Chapter XXXVIII. Hyacinth binds books for the Princess and rises in status at the bindery. The Princess claims to have lost interest in this project and Hyacinth has to acquire more books ‘from store’ via her servant Augusta. He begins to feel that ‘the democracy’ will look after its own future, and continues to feel pulled between sympathy for his mother and his aristocratic father. Hyacinth and the Princess josh each other regarding their political commitments, and he suspects that she might be going ‘too far’. The Princess wonders if her ‘saint’ Lady Aurora might marry Paul Muniment, with whom she is in love.

Chapter XXXIX. Rosy Muniment also thinks her brother Paul ought to marry Lady Aurora, and that he ought to stay clear of the Princess. When Paul visits the Princess she flirts with him and tells him about Mr Vetch’s anxieties and suspicions. She asks Paul to dissuade Hyacinth from making his grand self-sacrifice. Paul says that such a decision is Hyacinth’s own business. They leave for a meeting and are spied upon and followed by her husband the Prince.

Chapter XXXX. The Prince visits Madame Grandoni and asks her for information on the Princess and Paul Muniment, suspecting his wife of having an affair. Madame Grandoni is divided in her loyalty, but she reveals that they are all involved in overthrowing society. The Prince wishes to avoid a ‘scandal’ since he is inordinately proud of his family name. When Hyacinth suddenly appears the Prince quizzes him about his political opinions and wants to know about the house the Princess and Paul have gone to. The conspirators return: Hyacinth is disturbed and goes home.

Chapter XXXXI. Hyacinth goes into Hyde Park on Sunday with Millicent. She chides him for his inconstancy, his anti-social ideas, and his relationship with the Princess. She also correctly assumes that Paul has replaced him in the affections of the Princess.

Chapter XXXXII. The same evening Hyacinth calls on Lady Aurora who is going out to a party and seems ready to rejoin her class. Then he goes to the Poupins where they are entertaining Schinkel.

Book Fifth

Chapter XXXXIII. Although they welcome Hyacinth, he feels that there is something ominous afoot. He demands to know what is happening. They reveal that they think he has given up the cause, and Schinkel has a letter for him. They argue inconsequently.

Chapter XXXXIV. Hyacinth goes out, followed by Schinkel, who tells him about having received a letter for him. Hyacinth takes the letter, but when he goes up to his room Mr Vetch is waiting for him, worried that he might be in trouble. Hyacinth promises him never to do anything to help the revolutionaries, and Mr Vetch leaves.

Chapter XXXXV. Next day Hyacinth goes to the Princess’s house, only to find that Madame Grandoni has gone back to Italy. The Princess arrives, and they have a disagreement about his commitment to the ’cause’. She tells him that Paul thinks his ‘grand sacrifice’ will not be called in, because he has obviously changed his political allegiance. He claims not to have changed at all.

Chapter XXXXVI. Paul visits the Princess to tell her that her husband is cutting off her allowance. He predicts that she will return to the Prince. He also reveals that Hyacinth has received instructions to assassinate somebody in a few days time at a grand party. The Princess claims she will try to carry out the act herself.

Chapter XXXXVII. Hyacinth has three days left. He decides he would like comfort from Millicent, but when he goes to the shop where she works, she is serving Sholto. He feels that if he carries out the assassination he will be following in his mother’s footsteps. The Princess arrives at Hyacinth’s lodgings to find Schinkel also waiting for him. They break down the door, to find that Hyacinth has shot himself through the heart.

First edition – Macmillan 1886

The Princess Casamassima – principal characters

| I | an un-named narrator who occasionally appears |

| Miss Amanda Pynsent (‘Pinnie’) | an impoverished dressmaker, foster-mother to Hyacinth |

| Hyacinth Robinson | small, intelligent bookbinder of Anglo-French parentage |

| Mrs Bowerbank | a large woman who works as a prison officer |

| Millicent Henning | childhood playmate of Hyacinth who becomes a pushy cockney |

| Theophilous Vetch | a radical fiddle player and neighbour |

| Florence Vivier | a French prostitute, Hyacinth’s mother |

| Eustace Poupin | French republican exile and master bookbinder |

| Mr Crookenden | Soho bookbinder |

| Paul Muniment | a chemist’s assistant and radical, Hyacinth’s friend |

| Rosy Muniment | Paul’s sister, a cheerful invalid |

| Lady Aurora Langrish | tall, plain, ill-dressed aristocratic ‘socialist’ |

| Lord Frederick Purvis (‘Robinson’) | Hyacinth’s murdered father |

| Princess Christina Casamassima | a beautiful American woman |

| Prince Casamassima | her estranged Italian husband |

| Captain Godfrey Gerald Sholto | a ‘cosmopolitan’ friend of the Princess |

| Madame Grandoni | German companion to the Princess – an old woman who wears a wig |

| Diedrich Hoffendahl | a German revolutionary (who does not actually appear) |

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories