tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Tragic Muse first appeared as a serial in The Atlantic Monthly from January 1889 through to 1890. The novel was then presented in three volumes published in America by the Boston publishers Houghton, Mifflin and Company in 1890, and in England by Macmillan at virtually the same time. It is one of the longest of Henry James’ novels, and deals with a subject dear to his heart – the relationships between life and art.

first English edition in three volumes 1890

The Tragic Muse – critical commentary

The main theme

It is no surprise that this novel attracted very little attention when it was first published, and has generated so little citical commentary in the years since. The novel contains none of the careful organisation and tight structure of James’s more successful works, and its main theme of the artistic life versus social integration is not well realised.

Nick Dormer has a career as a member of parliament virtually handed to him on a silver dinner plate, but he turns it down in favour of his enthusiasm for painting. But his skill and his application as a painter are never convincingly presented. It is also difficult to believe that somebody would give up a parliamentary career on the strength of one painting which was deemed successful. He remains a weak and dilettantish figure throughout.

His sister Biddy’s activity as a sculptor is simply not realised at all. She merely hovers in her brother’s background as a fellow enthusiast.

Only Miriam’s transformation from pushy and ambitious would-be actress with few skills has any credibility attached to it. She develops via application and practice, through to a successful professional career. This part of the novel is altogether more convincing.

The length of the novel

This is possibly one of the slowest-moving of all James’s novels. It’s not only inordinately long (almost 200,000 words) but inordinately long-winded in terms of narrative technique and the recounting of events. The pace is so glacially slow at times that paragraph upon paragraph is devoted to issues as trivial as who might or might not turn up to a restaurant for lunch.

The result is a form of authorial ‘thinking out loud’ which includes multiple possibilities for almost every scene – all of which merely represent James’s point of view – not that of any of his characters. Thus the tale is essentially told, not shown.

James and the theatre

It is interesting to note that the overt subject matter of the novel (reflected in its title) of the stage and acting are topics which fascinated James and were to lead to his own ultimately disastrous excursions into playwrighting and the theatre. He converted his own early novel The American (1876) into a play which had modest success in the 1890s. On the strength of this he wrote a dozen plays, but all of them proved unsuccessful, and most famously his costume drama Guy Domville was booed off stage on its first night in England in 1895.

Nevertheless, although he was deeply wounded by the experience, he retained his interest in dramatic structures, and some of the works he conceived as dramas were later converted to novels which consist largely of conversations between the characters – such as The Other House (1896) and The Outcry.

It is also worth noting that almost all of his most carefully crafted works were later successfully adapted for the cinema – from Washington Square (1880) The Bostonians (1886) and The Portrait of a Lady (1881) to The Golden Bowl (1904). And a number of his shorter works have been turned into operas and plays, such as Owen Wingrave (1892) The Aspern Papers (1888) and The Turn of the Screw (1898).

However, despite the presence of drama in many of his novels and stories, the choice of theatre and acting as a serious topic for The Tragic Muse presents special difficulties for even so skilled a writer as James. It simply isn’t possible to give a convincing account of an evanescent art form such as the theatre in prose form.

He creates a persuasive sense that Miriam Rooth improves her acting skills as a result of learning from Madame Carré, and he evokes both the backstage and front of house atmosphere of the theatre very well, but the essence of what drama means eludes him.

The same is true in his choice of painting as Nick’s vocation. No matter how many brush strokes across canvass and paint-soaked rags are mentioned, it is virtually impossible to convey with words the visual quality of any work Nick produces. We are simply told that his portraits of Miriam (and he only paints two during the entire novel) are successful.

The actress

Contemporary readers might find it difficult to understand why Peter is confronted with a dilemma in his passion for Miriam. He is in love with her, but in order to make a relationship with her he must persuade her to give up the very thing in which she is passionately interested – the theatre.

During the nineteenth century (and into the middle of the twentieth) the profession of actress was regarded as not far short of prostitution. Peter is a diplomat – and could not possibly combine a relationship with an actress and his career.

There was a long-standing tradition of upper-class males who had casual and semi-official liaisons with actresses. One thinks of the Prince of Wales and Lillie Langtry (real name Emile Charlotte Le Breton). But these relationships could not normally be incorporated into polite society. In Peter’s own words of warning to Miriam “e;an actress would never be invited into the drawing room of a lady”e;.

So Peter realises that there is a total incompatibility between his duties and protocols as a diplomat and his passion for such a bohemian figure as an actress – a problem which he solves by his sudden decision to marry Biddy at the end of the novel.

Those who wish to take a psycho-analytic approach to the interpretation of the story will not fail to recognise that it is one (of many in James’s oeuvre) in which two men (very close friends, and cousins) are in love with the same woman – the magnetic figure of Miriam.

Loose ends

Given the enormous length of the novel, it is reasonable to complain that it contains far too many loose ends – lines of the plot which are unexamined, unfinished, or unexplained (to use the three part amplification figure which James employs throughout the narrative).

Nick’s elder brother, Percival Dormer, is suddenly mentioned towards the end of the novel, and for a moment it looks as if he will add to the significance of the family’s social fortunes – but he just as suddenly disappears and is never mentioned again. This is bad on two counts.

As the elder son, it is more likely that the family’s hopes would rest on him, not Nick. It is the elder son who would be expected to follow his father’s role in parliament, but all those hopes (and Mr Carteret’s money) are placed on Nick. These apparently minor details undermine a significant building block of the realist novel – social accuracy, plausibility, and consistency.

Biddy is an interesting character in embryo. She is spirited, independent, and like her brother inclined to practice art. But her activity as a sculptress is never persuasive and simply evaporates in the hurried and unsatisfying conclusion when she marries Peter and disappears to his next diplomatic posting.

Julia Dallow too is a potentially interesting character – a rich and attractive woman who wishes to engage in (Liberal) politics at a national and local level. She is the financial power behind the selection of a candidate for the constituency of Harsh – though it should be noted that this is a ‘rotten’ (more euphemistically a ‘pocket’) borough.

Gabriel Nash is like a Satan figure, coming in to plead the case for aestheticism and lure people (Nick in particular) away from their civic duty. Nash appears from nowhere, plants his ideas, then disappears again. Nobody knows where he lives, and when Nick tries to paint his portrait, he escapes, claiming to be ‘indestructible’.

The Tragic Muse – study resources

![]() The Tragic Muse – Library of America – Amazon UK

The Tragic Muse – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() The Tragic Muse – Library of America – Amazon US

The Tragic Muse – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Tragic Muse – Kindle edition

The Tragic Muse – Kindle edition

![]() The Tragic Muse – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

The Tragic Muse – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James – biographical notes

Henry James – biographical notes

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

The Tragic Muse – plot summary

Chapter I. Nicholas (Nick) Dormer is on a cultural visit to Paris with his widowed mother and sisters. Lady Dormer has severe doubts about the moral effects of the modern art they are viewing. Nick however believes that all art contributes to a general good.

Chapter II. Nick is the second eldest son of a politician and a would-be painter who is aware of his limitations. His sister Bridget (Biddy) wants to be a sculptor. They meet Gabriel Nash, who is an aphoristic conversationalist and an aesthete. Biddy is intrigued by him.

Chapter III. Grace Dormer and her mother go to lunch and discuss people’s marriage and money prospects. They are joined by their relative Peter Sherringham who reveals that Nick is being tipped for his father’s old seat as a member of parliament.

Chapter IV. Everyone thinks that Nick should ‘apply’ for the seat – but he needs money to do so (because it is a rotten borough). Nash is against the plan: he offers to introduce the family to his friend Miriam Rooth, an actress, and her mother. The theatre is considered as an artistic medium. Nick thinks it is a feeble art form; Sherringham is an enthusiastic supporter; and Lady Dormer disapproves of it completely.

Chapter V. His mother wishes that Nick were more active and enthusiastic about the chance of the parliamentary seat, and feels disappointed not to find Julia Dallow available as a potential financial supporter. Meanwhile Peter defends his enthusiasm for the theatre to Nick.

Chapter VI. The family have a restaurant dinner with Julia Dallow who is the power behind the appointment of a candidate at Harsh, her estate and parliamentary rotten borough. Julia and Nick then discuss his prospects. He is sceptical about standing: she is willing to put up the money in order to keep out the Tories.

Chapter VII. Nick and Peter meet Miriam Rooth and her mother at the home of Madame Carré. Miriam delivers recitations, but Madame Carré does not think she has any real talent. Peter however is keen to support and promote her.

Chapter VIII. Miriam and her mother are living in reduced circumstances. She gives another recital next day at an event organised by Peter. He is embarrassed by her performance and thinks her vulgar – but is nevertheless attracted to her.

Chapter IX. Gabriel Nash talks to Nick about his personal theories of the aesthetic life – turning his own feelings into a form of art. Nick is going to stand for parliament, but wishes to be a painter. He feels the force of the family’s political tradition as a burden.

Chapter X. Peter feels oppressed by the promise he has made to help Miriam, and he also fears he might be falling in love with her. She gives another pushy and bad recital chez Madame Carré. Peter also feels that critics treat actresses badly.

Chapter XI. Peter and Miriam discuss her life of poverty-in-exile and speaking styles in the theatre. He argues that she is without a genuine personality, but makes herself into a work of art, and is acting all the time.

Chapter XII. Peter is conscious that the protocols of his career in the diplomatic service mean that he should keep his theatrical enthusiasm under firmer control. He disregards Mrs Rooth’s superficiality, and the summer passes with MIriam still taking lessons from Madame Carré. Peter tries to educate her and pays for better lodgings. He thinks he might rise above personal issues, but when he goes back to London at the end of the summer he realises that he is completely in love with Miriam.

Chapter XIII. Nick is elected as Liberal Party member of parliament for Harsh. His mother wants him to marry Julia, who has financed his campaign. But Nick is reluctant, not really interested in politics, and wishes to retain his freedom. However, Lady Agnes argues that it would help her and his two unmarried sisters to establish themselves socially, and this touches his sense of family duty.

Chapter XIV. When Nick stays at Harsh with Julia and starts engaging with his political duties, he realises how they are enhanced by her presence.

Chapter XV. Nick rows out to an island on the lake at Julia’s estate at Harsh and proposes to Julia in a little Roman temple. They tease each other and he puts on a front of frivolity. Julia says his mother and sisters can live in one of her spare houses – Broadwood.

Chapter XVI. Nick visits his benefactor Mr Carteret at Beauclere and appreciate centuries of tradition that the house, grounds, and an old Abbey represents. Carteret is a liberal traditionalist with a well-informed but limited range of interests.

Chapter XVII. Next morning Carteret dispenses advice to Nick on his parliamentary responsibilities – which depresses Nick. But he approves of Nick’s marriage plans and promises to bestow money on him to give him financial independence. Nick however reveals that Julia wishes to wait for a year to be married.

Chapter XVIII. Peter feels that his ambition to succeed in his career is seriously compromised by his feelings for Miriam – who would be entirely unsuitable and unacceptable as a diplomat’s wife. He returns to Paris and encourages Mrs Rooth to take Miriam to London. She has meanwhile been taken up by admirer Basil Dashwood, who Peter claims to be keen to meet.

XIX. Peter follows Miriam and Dashwood to Madame Carré’s where she demonstrates that she has improved her skills. He befriends Dashwood and claims he has a potential engagement for Miriam arranged on the English stage.

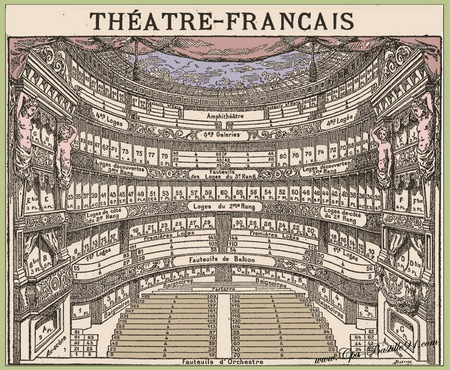

Chapter XX. Peter takes Miriam and her mother to the Theatre Francais where he gives them a tour of its professional inner mechanisms and architecture – the theatre as seen from an actor’s point of view.

Le Théatre Francais

XXI Peter flirts with Miriam and offers to take her away from the theatre. They meet the star actress Mademoiselle Voisin, who takes them to her dressing room. Miriam is very impressed by her urbane style and the tradition of theatre that she represents. Peter repeats his offer to marry her – arguing that if she remains as an actress she will be excluded from polite society.

XXII Nick is frustrated by Julia’s making him wait to be married. She wishes to mingle with political society, whereas he wants to get away from it. They come close to arguing, but she finally agrees to marry him in five week’s time.

XXIII Nick retreats to his artist’s studio for the Easter holidays, where he is visited by Gabriel Nash, who expounds his theories of aestheticism once more. On seeing Nick’s paintings and drawings he insists that Nick has a talent it would be immoral to neglect.

XXIV Nash thinks Nick ought to give up parliament and devote himself to painting. Nick is flattered but sceptical. Nash suggests that Nick should paint Miriam’s portrait.

XXV Nick has begun to paint Miriam’s portrait. She has become successful on the stage and patronises Peter. Nick is determined not to fall in love with her.

XXVI Miriam recounts the events of her theatrical success to Nick. It has been made possible by Peter’s buying the rights to a play, then giving them to her as a source of income. He continues with the portrait – only to be suddenly be confronted by Julia, who is shocked by the intimate scene she stumbles upon.

XXVII That evening Julia explains in a jealous fit that she thinks Nick prefers art to the political life she has created for him. She feels he has betrayed her, breaks off their relationship, calls on her old friend Mrs Gresham, and goes off to Paris.

XXVIII Julia meets her brother Peter in Paris and encourages him to pay attention to Biddy Dormer. Peter goes to London and tries to locate Miriam without success, but when he goes to Nick’s studio, he finds Biddy there.

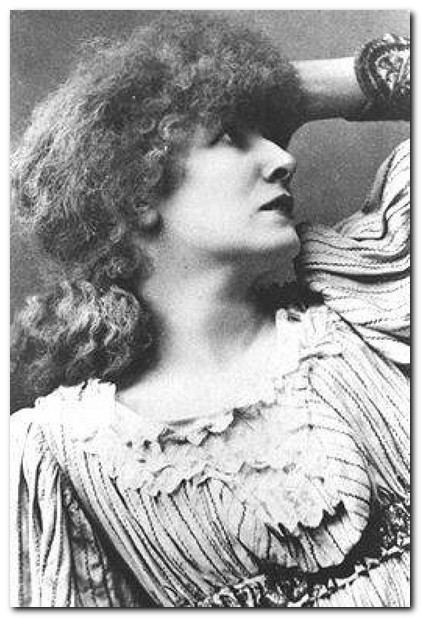

Sarah Bernhardt

XXIX Peter and Biddy discuss Nick and Julia’s problems, the fact that Lady Agnes is upset because none of her children are married. They also consider the value of art, for which Nick is going to give up his parliamentary seat. Biddy is sculpting and thinks she will never marry. They look at Nick’s portrait of Marian, which is very good.

XXX Peter takes Biddy and her friend to the theatre to see Miriam. He finds her transcendentally accomplished and develops grandiose visions of a publicly subsidised theatre. He discusses Miriam’s rise to fame with Dashwood, and feels patronised by him.

XXXI Peter spends the afternoon with Miriam and her arty hangers-on. She expands upon her ambitions. He becomes her regular coach and dramaturg. He regards Dashwood as a lightweight, but remains ambiguous in his feelings towards Gabriel Nash.

XXXII Mr Carteret becomes ill, and Nick is summoned to Beauclere. He feels ill at ease, partly because of his non-marriage to Julia, and partly because of his intention to quit parliament. Carteret summons him to tell him something important.

XXXIII Carteret want to know about Nick’s marriage to Julia, on which his promised financial settlement depends. Nick gives him an embarrassed explanation of that particular truth, which upsets the old man. Later the same day he demands the full story, and Nick is forced to reveal his plan to quit politics – as a result of which he will forfeit sixty thousand pounds.

XXXIV Nick is forced to reveal the whole story to his mother, who is mortified with disappointment. She feels that they might have to give up living at Broadwood following the rift with Julia and that Nick’s loss of Carteret’s legacy, plus giving up parliament is a shame the whole family must bear.

XXXV Nick is tempted to go abroad, but realises that he must stay and face the consequences of his actions. He is visited by Gabriel Nash, who reveals that Peter is in love with Miriam Rooth, who in her turn is in love with Nick – ever since the meeting and silent clash with Julia in the studio.

XXXVI Peter and Nash discuss Miriam’s prospects for success, and the fact that she is in love with Nick. Nash opines that she would give up the theatre for Nick – but that there would probably be a heavy price to pay.

XXXVII In Miriam’s bohemian late afternoon salon she bandies with Peter, flatters Nick, and treats Dashwood like a skivvy. Peter feels mildly jealous of her praise for his friend and cousin Nick.

XXXVIII Peter wonders why he feels any rivalry with his friend Nick when (theoretically) he has nothing at stake with Miriam. He applies for a new diplomatic posting and is given a position as ambassador to a state in Central America.

XXXIX Peter goes to see Lady Agnes, who is still eaten up with Nick’s giving up parliament and his loss of prospects. She takes an exaggerated interest in Peter’s career development and salary, which he realises is a poorly disguised wish that he should marry her daughter Biddy.

Sarah Benhardt as Cleopatra

XL Whilst Peter is preparing himself for a move to the tropics, he is summoned by Miriam to a dress rehearsal next morning. He goes, and is obviously under her spell.

XLI She summons him again the following day for a private assignation – but then forgets what she wished to discuss with him. He ends up confessing that he is leaving because he is desperately in love with her, and because he realises that a relationship with her is not possible.

XLII Nick has begun to regret giving up parliament, and doesn’t think he has any genuine artistic talent either. He is visited by Peter, who has conflicting social engagements with Miriam and Lady Agnes.

XLIII Biddy arrives at the studio and there is banter with Peter and Nick – then Miriam arrives with her mother. Peter and Biddy go shopping and discuss Miriam, on which topic Biddy full of practical good sense.

XLIV Arriving at the studio, Miriam and her mother flatter Nick – and themselves. Nick continues a second portrait of Miriam promised to Peter whilst Mrs Rooth evaluates his belongings. The two women have invited Biddy to visit them, and they discuss Miriam’s strategy for dealing with Peter.

XLV In the evening the first night of Miriam’s new play is a resounding success. Peter refuses to go back stage with Nick in the intervals, but at the final curtain he sends a request to Miriam on a visiting card – which she accepts.

XLVI Peter goes back to Miriam’s house, where she joins him. He offers to marry her if she will give up the theatre. She refuses. They argue about the social and moral merits of the theatre. In desperation he asks for re-consideration in a year’s time. Mrs Rooth then arrives and promises to help him.

XLVII Nick continues to drift morally, but when Julia returns from her travels abroad he feels that the family should give back the house they have borrowed from her. Julia accepts their offer, but then invites Biddy to live with her at Harsh. She then moves back into Broadwood and asks Lady Agnes and Grace to join her there again.

XLVIII Miriam continues to be more and more celebrated, but Nick’s second portrait of her is unfinished. She visits for a sitting, flirts and philosophises with him, then leaves for a theatrical tour of the provinces.

XLIX Gabriel Nash visits Nick’s studio and predicts that Nick will reach a compromise with Julia and will end up a painter of society portraits. Nick begins to paint Nash’s portrait, but Nash feels uncomfortable, argues that he is ‘indestructible’ and then suddenly disappears – never to return.

L Some months later Nick spends Xmas at Broadwood with his mother and sisters, then goes to Paris for six weeks. Biddy visits Nick’s studio to tell him that Julia wants him to paint her portrait. Miriam suddenly appears with Dashwood, ready for the first night of her new role as Juliet. She arranges a box for Nick and Biddy.

LI At the theatre that night Peter suddenly appears, back from his posting in the Americas. Nick reveals to him that Miriam has just married Dashwood. Peter immediately switches his attention to Biddy, then marries her and takes her on to his next posting abroad.

Henry James’s study

The Tragic Muse – principal characters

| I | an un-named narrator who makes occasional appearances |

| Lady Agnes Dormer | a haughty and traditionalist widow |

| Percival Dormer | her eldest son, who never appears |

| Nicholas Dormer | her younger son, a reluctant politician and would-be painter |

| Grace Dormer | her eldest daughter |

| Bridget (Biddy) Dormer | her youngest daughter, and would-be sculptor |

| Peter Sherringham | a family cousin and diplomat, with an enthusiasm for the theatre |

| Mrs Julia Dallow | Peter’s sister, a rich widow |

| Gabriel Nash | an aesthete friend of Nick’s from Oxford |

| Miriam Rooth | a half-Jewish actress |

| Mrs Rooth | her mother, a widow |

| Rudolph Roth | Miriam’s father, an artistic stockbroker |

| Madame Carré | an old French actress |

| Mr Carteret | a family friend and financial supporter of Nick |

| Mts Gresham | a general factotum to Julia at Harsh |

| Basil Dashwood | actor and admirer of Miriam |

Further reading

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories