tutorial, commentary, study resources, web links

Wingstroke was written in October 1923 and was first published in the Russian emigré periodical Russkoye Ekho for January 1924. It is quite possible that the story is unfinished, since Nabokov mentioned in a letter to his mother that he had written a continuation to the tale. The story also has numbered sections, which suggests that it is a fragment of what was planned as a longer work.

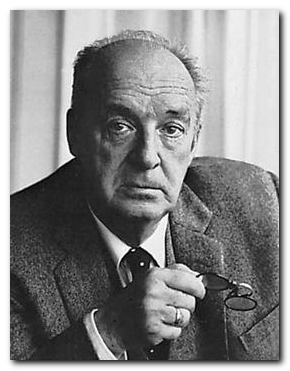

Vladimir Nabokov

Wingstroke – critical commentary

Young men in states of existential anxiety are quite common in Nabokov’s early fiction. One thinks of the 1924 story, A Matter of Chance (1924) – and indeed they persist as late as the novella The Eye (1930) and his novel Despair (1936). This is not counting the inspired madmen who continue through to Humbert Humbert in Lolita (1955) and Charles Kinbote in Pale Fire (1962).

The protagonist Kern has a rational source for his state of unease: his wife has betrayed him with another man, then killed herself on discovering her lover was a rogue and a thief. But there are also hints that Kern might be unwell. He is repeatedly beset by pains in his chest and presentiments of death.

In fact there are several pre-echoes of death throughout the story. Isabel explains to Kern her exhilaration at skiing dangerously at night, pre-figuring exactly what does happen to her, only a few pages later:.

“It was extraordinary. I hurtled down the slopes in the dark. I flew off the bumps. Right up into the stars.”

”You might have killed yourself,” said Kern.

Shortly afterwards Kern feels that ‘He had the sensation that he had glanced into death.’ There are far too many symbolic references for a simple short story, and another reason to believe that what exists of Wingstroke is a fragment of what was originally conceived as a longer work.

There is also the problem of what is presumably an unintended suggestion. Whilst Kern is grappling with his desire for Isabel he is picked up by the character Monfiori, who is clearly a homosexual Monfiori warns Kern against Isabel: “She’s a woman. And I, you see, have other tastes.” He is quite open about his intentions, telling Kern:

“I search everywhere for the likes of you – in expensive hotels, on trains, in seaside resorts, at night on the quays of big cities.”

Yet at the conclusion to the story, as the two males return to the hotel following Isabel’s fatal accident on the ski slope, Kern makes a very suggestive invitation to Monfiori:

”I am going upstairs to my room now … Upstairs … If you wish to accompany me”

By all the conventions of fictional development and narrative logic, this can only be interpreted as a suggestion that Kern is accepting Monfiori’s gay advances.

Nabokov has a number of homosexual characters in his fiction, but they only ever feature as figures of derision. It is very unlikely (and it would be unique in his oeuvre) if he were suggesting that Kern is escaping from disappointment over his wife’s death and his fascination regarding Isabel – into the arms of a short man with red hair and ‘pointed ears, packed with canary-coloured dust, with reddish fluff on their tips’. This is simply not Nabokov’s style at all.

Study resources

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov – Amazon UK

Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

The Paris Review – Interview

First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Wingstroke – plot summary

1 Kern is a thirty-five year old man staying in a Zermatt hotel during the winter skiing season. He is in an emotionally depressed state since his wife of seven years has fallen in love with someone else, then when he turned out to be a thief and a liar, has killed herself by taking poison. Kern is attracted to Isabel, a glamorous English fellow guest in the hotel. He dances with her, then finds it difficult to get to sleep afterwards, because she is in the next room, is playing a guitar, and has a noisy dog.

2 Next day she denies having made any noise. Kern is invited to the bar by the homosexual Monfiori who advises him to forget Isabel. The two men consume lots of cocktails, and Kern tell Monfiori that he is planning to kill himself next day. Monfiori says he wants to watch.

Kern goes up to his room quite drunk, then remembers that Isabel is next door. When he goes to her room she rushes out, and Kern is confronted by what he perceives as a dishevelled Angel who has come in through the window, but is clearly the dog that has followed Isabel to the hotel. He stuffs the dog into a wardrobe, collects Isabel, and goes back to his room where he tries to write an important letter announcing his suicide.

3 Next day he cannot find the letter, but still plans to shoot himself at lunch time. He goes to watch the ski jumping event where Isabel is competing. But on her jump, she falls from mid air and is killed. Kern returns to the hotel and invites Monfiori to join him in his room.

Other work by Vladimir Nabokov

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness. ![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Vladimir Nabokov links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov – life and works

Vladimir Nabokov – life and works

![]() Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories – critical analyses

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories – critical analyses

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: an illustrated life

Vladimir Nabokov: an illustrated life

© Roy Johnson 2017