tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

An Imaginative Woman was first published as a serial in Pall Mall Magazine in 1894. It was originally part of Wessex Tales (1896) but Hardy moved it into his collection Life’s Little Ironies (1912) for reasons that he explains rather cryptically in his preface, but which throw some light on how he meant it to be understood:

turning as it does upon a trick of Nature … a physical possibility that may attach to a wife of vivid imaginings, as is well known to medical practitioners and other observers of such manifestations.

There isn’t actually any ‘medical’ issue involved in the denouement of the story, so Hardy seems to be indulging in a little teasing provocation in this explanatory note. But it does hint at the crucial dramatic irony on which the story hinges that is discussed in the critical commentary below. It’s one of a number of stories Hardy wrote on the theme of injudicious or unsatisfactory marriages – For Conscience’ Sake and To Please His Wife are other typical examples. And of course Hardy had his own experience as first hand evidence of early-life romances which can lead into middle-aged misery.

Thomas Hardy

An Imaginative Woman – critical commentary

Irony – I

Contemporary readers can be forgiven if they do not spot the very delicate but crucial irony that Hardy inserts into the pivotal scene in the story when Ella undresses herself for a quasi-erotic solitary contemplation of Trewe’s photograph. Her rapture is interrupted when her husband Marchmill returns unexpectedly, and after refusing her hint that he sleep in another room (a passage from the original manuscript omitted from The Pall Mall Magazine publication) he kisses her and says “I wanted to be with you tonight.”

The very understated implication is that they have sex together that particular night. It was impossible to be explicit about such matters, writing at this time. So Marchmill’s final suspicion at the end of the story that his wife has been unfaithful to him during their holiday is doubly ironic. It was something she was trying desperately to achieve – but failing to do so. But the major point is that the child is certainly Marchmill’s, even though he rejects it.

The reader knows that Ella never gets to see or meet Trewe, even though she puts on his clothes, worships his photograph, and sleeps in his bed. Marchmill on the other hand is oblivious to his wife’s feelings and aspirations throughout the story, yet when he finally does come to feel a form of retrospective jealousy his suspicions lead him to a conclusion which is understandable but false.

This might seem to be playing fast and loose with the reader, but Hardy was writing under the very severe restrictions exercised by publishers at the time. It should be remembered that he stopped writing novels because of the outrage generated by Jude the Obscure. He turned his attention to poetry instead, and is now regarded as one of the greatest English poets of the period.

Irony – II

A second example of irony is that Trewe’s last poems were entitled Lyrics to a Woman Unknown, and he leaves a letter addressed to a friend in which he explains his yearning for a woman he has not actually met:

I have long dreamt of such an unattainable creature, as you know; and she, this undiscoverable, elusive one, inspired my last volume: the imaginary woman alone

So, at the same time that Ella has been pining after a Trewe she had never met, he has been searching for a female soul mate. They never actually meet; neither of them get what they want; and they both end up dead. You can see why Hardy is renowned for his tragic pessimism.

A curious feature

Robert Trewe commits suicide in the story by shooting himself in the head with a revolver – and yet he is buried in a cemetery. In the nineteenth century the stigma against suicide meant that the church would not normally allow someone who had taken their own life to be buried in consecrated ground. Hardy was well aware of these social prohibitions, as he had already demonstrated in Far from the Madding Crowd when Fanny is forced to bury her illegitimate dead child outside the graveyard. So it is slightly puzzling that he include such a scene in this story – unless he was merely reflecting the loosening of a formerly rigid social convention.

An Imaginative Woman – study resources

![]() Life’s Little Ironies – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

Life’s Little Ironies – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() Life’s Little Ironies – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

Life’s Little Ironies – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() Life’s Little Ironies – Wordsworth Classics edition – Amazon UK

Life’s Little Ironies – Wordsworth Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

![]() Life’s Little Ironies – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

Life’s Little Ironies – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() Life’s Little Ironies – audiobook version at Project Gutenberg

Life’s Little Ironies – audiobook version at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

An Imaginative Woman – plot summary

Ella Marchmill is a romantic young woman with an artistic temperament and an unfulfilled personal life. She is bored with her marriage, and has written and published poetry under the pseudonym John Ivy. On holiday with her husband and three children in Solentsea (Southsea) they find lodgings normally occupied by a young poet Robert Trewe, who moves out to accommodate them.

Ella Marchmill is a romantic young woman with an artistic temperament and an unfulfilled personal life. She is bored with her marriage, and has written and published poetry under the pseudonym John Ivy. On holiday with her husband and three children in Solentsea (Southsea) they find lodgings normally occupied by a young poet Robert Trewe, who moves out to accommodate them.

Ella finds scraps of poetry written on the walls of Trewe’s room, reads the books he has left there, and becomes caught up in a romantic dream of their being soul mates, even though she has never met him or even seen him.

Various arrangements are made whereby he might call at the lodgings, giving her the chance to meet him, but they all come to nothing. Then she writes to him under her pseudonym and sends him some of her poems.

The Marchmills return home, and a family friend who is on holiday with Trewe is invited to stay en route back home. The friend arrives, but Trewe does not, apologising that he is in a depressed state of mind.

Shortly afterwards, Trewe commits suicide. Ella travels secretly to the burial, and is followed there by her husband, who is tolerant of her behaviour,

Ella subsequently has a fourth child, and dies as a result. Her husband finds that she has kept a photograph of Trewe and a lock of his hair as a romantic memento. He compares the hair with that of his new young son and falsely concludes that there has been a liaison between his wife and the poet whilst they were on holiday. He rejects the child.

Principal characters

| William Marchmill | a gunsmith from the English midlands |

| Ella Marchmill | his wife, a romantic and unfulfilled woman (30) |

| Mrs Hooper | a widowed boarding house landlady |

| Robert Trewe | a romantic poet (30) |

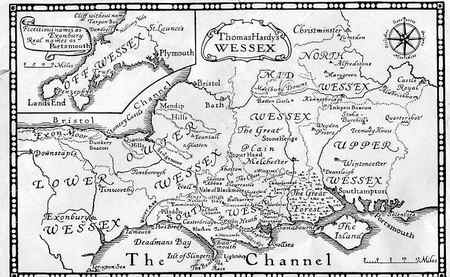

Hardy’s WESSEX

Further reading

![]() John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

![]() Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

![]() L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

![]() Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

![]() R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

![]() Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

![]() James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

![]() Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

![]() P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

![]() P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

![]() Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

![]() R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

![]() Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

![]() F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

![]() Norman Page, Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

Norman Page, Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

![]() Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

![]() Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

![]() Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

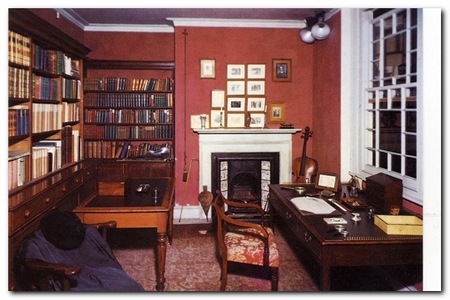

Hardy’s study

reconstructed in Dorchester museum

Other works by Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Thomas Hardy – web links

![]() Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, book reviews. bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Collection

The Thomas Hardy Collection

The complete novels, stories, and poetry – Kindle eBook single file download for £1.29 at Amazon.

![]() Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, the novels and literary themes, poetry, religious beliefs and influence, biographies and criticism.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Society

The Thomas Hardy Society

Dorset-based site featuring educational activities, a biennial conference, a journal (three times a year) with links to the texts of all the major works.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Association

The Thomas Hardy Association

American-based site with photos and academic resources. Be prepared to search and drill down to reach the more useful materials.

![]() Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production features, box office, film reviews, and even quizzes.

![]() Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Small collection of academic papers and articles ‘favoring signed articles by recognized scholars and articles published in peer-reviewed sources’.

![]() Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Evolution of Wessex, contemporary reviews, maps, bibliography, links to other web sites, and history.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More on Thomas Hardy

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories