restoring a Bloomsbury decorated house

Charleston is a farmhouse near Lewes, Sussex which was once the home of Clive Bell, his wife Vanessa, and her lover Duncan Grant. Leonard and Virginia Woolf were frequent visitors from their own country property at Monk’s House in nearby Rodmell. Other members of the Bloomsbury Group such as Lytton Strachey, David Garnett, and Maynard Keynes were regular visitors.

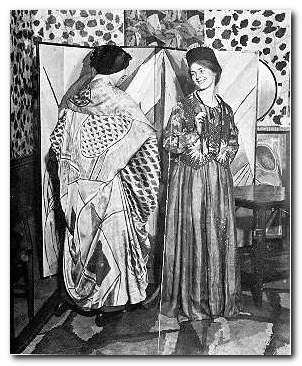

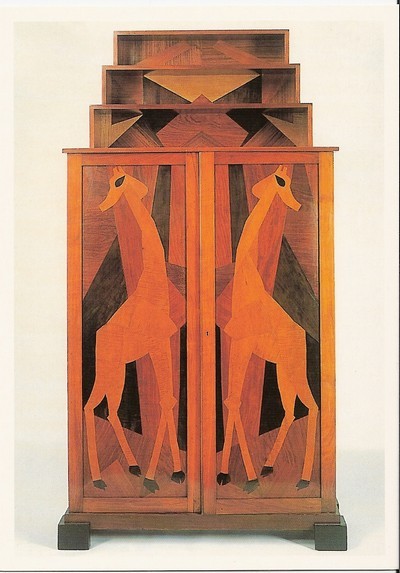

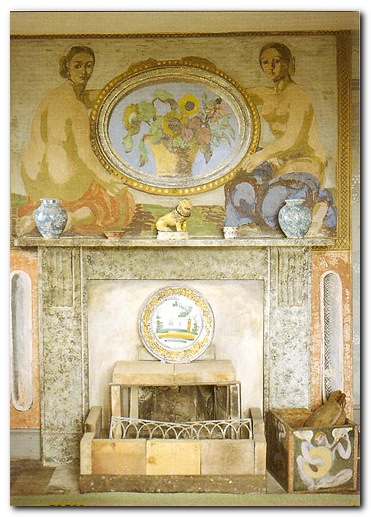

It is most famous for the fact that Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant covered the entire surface of the house – walls, fireplace, cupboards, tables, chairs – with their decorations and paintings, an impulse that was also part of the Omega Workshops movement initiated by Roger Fry around the same time during the first world war. [A subsidiary purpose of the house was to act as a refuge for conscientious objectors to the war.]

It is most famous for the fact that Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant covered the entire surface of the house – walls, fireplace, cupboards, tables, chairs – with their decorations and paintings, an impulse that was also part of the Omega Workshops movement initiated by Roger Fry around the same time during the first world war. [A subsidiary purpose of the house was to act as a refuge for conscientious objectors to the war.]

The house was famously damp and rather uncomfortable, but Duncan Grant went on living there until his death in 1978 – at which point it was in a state of neglect and dilapidation. This book is an account of the restoration project made to bring the hopuse back to life – ‘from the Broncoo toilet paper to the Bakelight electrical fittings’. Indeed throughout the whole project there was a constant debate over the relative merits of re-creating the original or saving what was left, which was a very expensive option.

There’s a great deal of fund-raising by the great and the good, but the real interest of Anthea Arnold’s account is in how a decaying over-decorated farmhouse can be pulled back from the brink of disintegration whilst preserving its spirit and integrity. There was much to be done against death watch beetles, mold, dry rot, and general decay.

At some points the narrative becomes a somewhat bizaare mixture of raffle prizewinners at fundraising events sandwiched between detailed technical accounts of replastering walls using goat’s hair bonding agents.

Chapters are ordered by the objects and materials being restored – furniture, ceramics, fabrics, stained glass, pictures, the garden – and most problematic of all, the original wallpaper. Yet desite all the nit-picking over minor details of wallpaper pattern repeats and curtain fabrics, the house was re-opened to the public without the fundamental problem of rising damp having been solved. Plaster had to be cut back to the bare wall more than once.

There was quite a lot of disagreement over the wisdom and accuracy of the restoration. Why spend tens of thousands of pounds preserving rotting wallpaper when the original designs could easily be reproduced? In the end, the argument for authenticity prevailed – so long as there were sufficient US-funded endowments to sustain it.

Anyway, the project finally succeeded, and Charleston is now a thriving visitors’ centre, and the location of an annual arts festival. So – Bloomsbury fans apart, this is a book that could appeal to public relations buffs and fundraisers, or to fans of Grand Designs or property restoration specialists.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Anthea Arnold, Charleston Saved 1979-1989, London: Robert Hale, 2010, pp. 144, ISBN: 0709090188

More on art

More on design

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

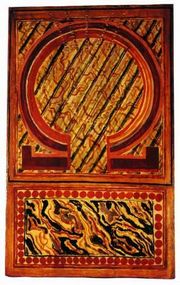

It opened in 1913 at the worst possible time in commercial terms, at 33 Fitzroy Square in the heart of Bloomsbury.

It opened in 1913 at the worst possible time in commercial terms, at 33 Fitzroy Square in the heart of Bloomsbury.  At the launch of the project, artist and writer Wyndham Lewis was also a member; but he quickly split away from the group in a dispute over Omega’s contribution to the Ideal Homes Exhibition. Lewis circulated a letter to all shareholders, making accusations against the company and Roger Fry in particular, and pouring scorn on the products of Omega and its ideology. This subsequently led to his establishing the rival Vorticist movement and the publication in 1916 of its two-issue house magazine, BLAST.

At the launch of the project, artist and writer Wyndham Lewis was also a member; but he quickly split away from the group in a dispute over Omega’s contribution to the Ideal Homes Exhibition. Lewis circulated a letter to all shareholders, making accusations against the company and Roger Fry in particular, and pouring scorn on the products of Omega and its ideology. This subsequently led to his establishing the rival Vorticist movement and the publication in 1916 of its two-issue house magazine, BLAST.