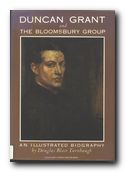

richly illustrated biography and social study

Duncan Grant came from a privileged upper class family in Scotland where he spent childhood holidays with his cousins the Stracheys (including Lytton Strachey who later became his lover) amidst a family whose eccentric behaviour reads like the events of a PG Wodehouse story. He went to Rugby School with Rupert Brooke and then lived with Lytton Strachey at Lancaster Gate. Duncan Grant and the Bloomsbury Group concentrates on his life and work amidst this illustrious collection of aesthetes.

Douglas Turnbaugh’s narrative weaves in an out of his many affaires as a young man – Strachey, Arthur Hobhouse, John Maynard Keynes – but also emphasises his hard work in trying to become a successful artist, studying the old masters, copying them, and attending art schools in London and Paris. Grant’s life merged with that of the Bloomsbury set when he took up residence with the Stephens in Gordon Square. He and Keynes lived on the ground floor; Adrian Stephen on the first floor; Virginia Woolf on the second; and Leonard Woolf on the top floor.

Douglas Turnbaugh’s narrative weaves in an out of his many affaires as a young man – Strachey, Arthur Hobhouse, John Maynard Keynes – but also emphasises his hard work in trying to become a successful artist, studying the old masters, copying them, and attending art schools in London and Paris. Grant’s life merged with that of the Bloomsbury set when he took up residence with the Stephens in Gordon Square. He and Keynes lived on the ground floor; Adrian Stephen on the first floor; Virginia Woolf on the second; and Leonard Woolf on the top floor.

He joined the Omega workshop which was organised by Roger Fry, subsequently replacing him as Vanessa Bell’s lover – despite the fact that he was her brother’s lover at the time. Then during the war he was like most of the Bloomsberries a conscientious objector. He became the father of Vanessa Bell’s daughter Angelica, who was passed off as the daughter of Clive Bell – to whom Vanessa was still married.

In the 1920s Vanessa learned to tolerate his affairs with a succession of younger men. In fact the whole family became involved in this sexual ambiguity when Julian Bell, Vanessa’s son, studying at Cambridge, began sleeping with Anthony Blunt – who later turned out to be simultaneously Keeper of the Queen’s pictures and a Soviet spy.

The cruelty of concealing the true identity of Angelica Bell’s father came home to roost in the late 1930s when she discovered the truth, and reacted to it by marrying another of her father’s ex-lover, David Garnett – which caused a rift in the family. [She gives her own account of these events, plus a picture of her Bloomsbury childhood, in Deceived with Kindness.]

In 1946, at the age of 60, he met the young Paul Roche, who was to be the main love of his late life and a serious threat to Vanessa. His work in the immediate post war period was considered unfashionable, but he continued working, mainly on decorative projects and private commissions. In the 1960s and 70s however, his reputation revived and he continued painting and pursuing young men with a remarkable degree of success until his death at the age of ninety-three.

This is a rather uncritical biography, but it captures the spirit of the ages in which Duncan Grant lived quite well, and it is rich in anecdote. The book is generously illustrated with Grant’s work and portraits of the Bloomsberries, and it has a good bibliography. I bought my copy second hand on Amazon to flesh out my collection of Bloomsbury materials, and although it is a little dated it turned out to be really good value.

© Roy Johnson 2002

Douglas Turnbaugh, Duncan Grant and the Bloomsbury group, London: Bloomsbury, 1987, pp.192, ISBN 0747501033

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature