sample from HTML program and PDF book

1. Editing essays or any piece of writing before you submit it for assessment is a sure way of improving its quality. Only very skilled writers can produce work without making mistakes. The elimination of small errors will improve the appearance and effectiveness of what you write.

2. The difference between a first and second rate piece of work may rest on just a little extra time spent checking what you have written. Read through your work carefully and correct any errors.

3. If necessary, read the essay out loud to check its grammar and correctness, but keep in mind that a conversational tone is not appropriate in essays.

4. Eliminate any sloppy or muddled writing. If something strikes you as weak or unclear, take the trouble to put it right. If this is not possible, be prepared to eliminate it from the essay.

5. Check for sentences which are grammatically incomplete. Look out for those which might lack any part of the Subject-Verb-Object minimum for grammatical coherence.

6. Check for missing words. Insert them into even the neatest completed typescript or manuscript. If you are using a word-processor, a grammar-checker might help you here.

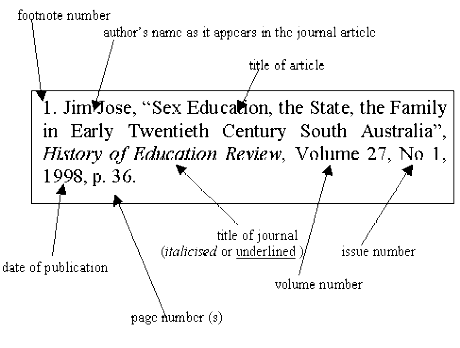

7. Check that you have spelled correctly any proper names, technical terms, or lesser-known words. If in doubt, look them up in a good dictionary. Use the spell-checker if your word-processor has one.

8. Check that your punctuation is consistent, accurate, and legible.

9. Check for consistency in the layout of your pages.

10. If your final draft contains a lot of mistakes and corrections, be prepared to re-write it, even if this will take quite some time. This will give you the opportunity to improve your presentation, and you will probably discover that you can introduce further improvements to the arguments.

Checklist

- Eliminate any awkward turns of phrase

- Split up any sentences which are too long

- Re-arrange the order of your paragraphs

- Eliminate any repetitions

- Correct errors of spelling or punctuation

- Create smooth links between paragraphs

- Add anything important you have missed

- Delete anything which is not relevant

- Check for weak syntax and grammar

- Run the grammar-checker and spell-checker

© Roy Johnson 2003

Buy Writing Essays — eBook in PDF format

Buy Writing Essays 3.0 — eBook in HTML format

More on writing essays

More on How-To

More on writing skills