tutorial, study resources, plot, and web links

Trilby was first published in serialised form in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in seven monthly instalments beginning January 1894. As was common practice at that time, each episodes carried illustrations featuring key figures and moments in the story. These were produced by the author himself, since George du Maurier was primarily a cartoonist and illustrator, even though he is best remembered today as the author of this novel, which he wrote at the suggestion of his friend Henry James.

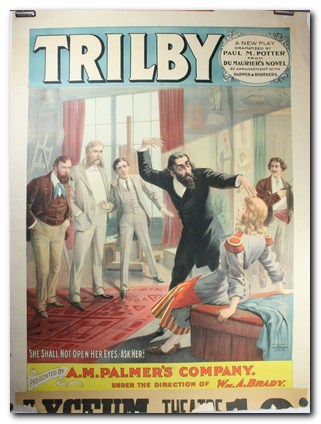

The book was an immense international success when it appeared, and it led to a version as a play (by Paul Potter) to various spoofs and parodies, and of course to the popularity of the trilby hat, which was a feature of the theatrical production. There were several later film versions of the story produced between 1914 and 1954 – one of which is featured below. George du Maurier was the grandfather of the English romantic novelist Daphne du Maurier (1907-1989).

Trilby – critical commentary

Historical background

In 1848 Alexander Dumas published The Lady of the Camellias (La Dame aux camelias) – a novel that established the fashion for stories set in the bohemian world of the demi-mondaine – a woman who trades her sexual favours in exchange for living in style. Dumas’s heroine has the additional interest that she is suffering from tuberculosis. The novel was immediately followed in 1852 by a very successful stage adaptation, and this in its turn was used as the basis for Giuseppi Verdi’s opera La Traviata.

Around the same time Henri Murger wrote his Scenes from Bohemian Life (Scenes de la vie de bohème) a loosely related collection of stories which originally appeared in the literary magazine Le Corsaire, all of them set in the Latin Quarter of Paris . They became known collectively under the title La Vie Bohème. These stories too gave rise to the romantic and sentimental plot for operas such as Puccini’s La bohème (1896) and various other adaptations for the stage and (later) the cinema.

Bohemia

“To be young, to be fond of pleasure, to care nothing for worldly prosperity, to scorn mere respectability, and to rebel against rigid rule – these are the qualities which alone may be regarded as essential to constitute the Bohemian.” That’s how the Westminster Review, a British journal, defined Bohemianism in 1862.

These literary predecessors to Trilby were second rate inventions, full of unrealistic cliches of artistic life – people with artistic aspirations living in cheerful poverty; whores with hearts of gold; sentimental love attachments, and eternal friendships sworn between men. George du Maurier featured all of these in Trilby, and added plenty more besides.

And yet the three principal males in Trilby – Taffy, the Laird, and Little Billee – are anything but genuine bohemians. They all have private incomes, they dine in the best restaurants, and they dress like City stockbrokers. They form a vaguely homo-erotic trio who accept Trilby on her boyish, de-sexualised arrival, but are scandalised (Billee in particular) when it is revealed that Trilby is working as an artist’s model, posing in the nude.

Du Maurier’s novel is an appalling production as a literary artefact. It is full of stock characters, poor construction, bad plotting, digressions and irrelevancies, and a laboured literary style that groans under the effort of fulfilling the demands of the monthly instalment.

But like other works in the genre of Gothic horror – Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde (1886), The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and Dracula (1897) du Maurier had a dramatic trump card that lifted a badly-written novel into the realms of the first modern best-sellers. That trump card was a psychological angle to the story that resonates beyond its historical milieu – the transformative power of hypnotism.

Hypnotism

Hypnosis derives from mesmerism, popularised by the German physician Franz Mesmer in the early nineteenth century. By the end of the century public demonstrations were commonly staged, and it is worth noting that some of the earliest researches into psycho-analysis (Freud and Charcot in 1885) used hypnosis as an attempt to access what we now call the unconscious mind.

The central character and villain Svengali uses hypnotic techniques, first of all to cure a painful condition of the eyes from which Trilby is suffering. At this point in the narrative she dislikes him intensely, and shortly afterwards she leaves Paris and the plot of the novel. In the five years that follow, she makes her way back to Paris and Svengali, where he hypnotises her again in order to teach her singing. At the same time he also makes her virtually his wife.

It is significant (for this novel) that an alternative name for mesmerism was ‘animal magnetism’. Trilby by the latter part of the novel has been living with Svengali in the intervening five years as his musical and life companion and is utterly devoted to him. The only logical explanation for this change in her attitude is that she is under his persuasive influence.

Svengali has hypnotised her into loving him – at the same time as teaching her to sing . He has done this with the use of his suggestively symbolic ‘little flexible flageolet’. Du Maurier seems to be unaware that a flageolet, apart from its metaphoric male counterpart, is anything but flexible.

The sexual element

Du Maurier also seems to be completely uncertain about his heroine – presenting her first as an androgynous boy-like figure, then as the whore with a heart of gold. In some passages Trilby is aware that her reputation is compromised, yet in others the narrative (which is firmly in the voice of its author) gives the impression that it is completely unblemished. However, it has to be said that given the social and literary conventions of the time, nobody would have published a novel that featured as its heroine a prostitute, heart of gold or not

And although it remains unacknowledged, that is what Trilby is. She is from a poor background with alcoholic parents, and she has been molested by an elderly friend of the family. She lives in the louche Latin Quarter of Paris, and poses in the nude as an ‘artists model’ and works occasionally a laundress. These are all what in the late nineteenth century were cyphers for prostitution.

She offers to live with Billee as his mistress because she loves him – but does not think she ought to marry him. She realises that her social reputation is tainted – and she feels shame about the ‘things’ she has done. She writes to Sandy:

And I have done dreadful things besides, as you must know, as all the Quartier knows. Baratier and Besson, but not Durian, though people think so. Nobody else I swear – except old Monsieur Penque at the beginning, who was mamma’s friend. It makes me almost die of shame and misery to think of it: for that’s not like sitting I knew how wrong it was all along – and there’s no excuse for me, none.

The implication is that she has had sexual relations with these artists, as well as posing nude for them. Later in the narrative she claims she ‘could never be fond of [Svengali] in the way he wished … I used to try and do all I could – be a daughter to him, as I couldn’t be anything else’.

Du Maurier is trying to redeem his heroine, but he seems to be struggling with his own ambivalences and contradictions, because in the same speech Trilby goes on to reveal ‘I always had the best of everything. He insisted on that … as soon as I felt uneasy about things … he would say “Dors, ma mignonne” and I would sleep at once – for hours, I think – and wake up, oh, so tired! and find him kneeling by me’.

The clear implication is that Svengali puts Trilby into a hypnotic trance and has sex with her – which accounts for her tiredness on waking. Yet du Maurier seems hardly aware of these inferences – because he no doubt wished to present his heroine as untainted.

Anti-semitism

Even the most enthusiastic reader will not fail to notice that the characterisation of Svengali is an almost grotesque example of anti-Semitism on du Maurier’s part. Svengali lives off the generosity of his relatives somewhere in Austria, and du Maurier describes him quite uncompromisingly (and redundantly) as an ‘Oriental Semite Hebrew Jew’. Svengali is physically filthy, with long hair, a big nose, and dirty fingernails. He borrows money that he does not repay, and he speaks in a (well-rendered) parody of Judeo-Teutonic speech. Unlike the three upright British heroes of the novel, he is licentious and deceitful too – since he has a wife and children whom he has abandoned. He has ‘special skills’ (his musical ability) as well as being a master of occult practices (hypnotism) that give him mastery over Anglo-Saxon maidens such as Trilby. He is also filled with malevolent intent towards all and sundry:

Svengali walking up and down the earth seeking whom he might cheat, betray, exploit, borrow money from, make brutal fun of, bully if he dare, cringe to if he must – man, woman, child or dog

As an intrusive and more-or-less first person narrator, du Maurier puts no distance between himself and the relentless prejudice manifest towards this character. And to underscore the fact that his attitude is racially motivated (rather than the criticism of an individual) he demonstrates the same attitude to the minor character of Mimi la Salope – Svengali’s earlier pupil, who is also Jewish:

she went to see him in his garret, and he played to her, and leered and ogled, and flashed his bold, black, beady Jew’s eyes into hers, and she straightaway mentally prostrated herself in reverence and adoration before this dazzling specimen of her race. So that her sordid, mercenary little gutter-draggled soul was filled with the sight and sound of him, as of a lordly, godlike, shawm-playing, cymbal-banging hero and prophet of the Lord God of Israel-David and Saul in one!

Trilby – study resources

![]() Trilby – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Trilby – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Trilby – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Trilby – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() Trilby and Other Works – Kindle – Amazon UK

Trilby and Other Works – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Trilby and Other Works – Kindle – Amazon US

Trilby and Other Works – Kindle – Amazon US

Trilby – film version

John Barrymore in 1931 film adaptation

Directed by Archie Mayo. Screenplay by J. Grubb Alexander. Starring John Barrymore (Svengali), Marian Marsh (Trilby O’Farrell), Donald Crisp (the Laird), Bramwell Fletcher (Little Billee), Louis Alberni (Gecko), Filmed at Warner Brothers Studios, California, USA.

Trilby – chapter summaries

Part First In a bohemian studio in Paris, the pianist Svengali meets artist’s model Trilby, who sings out of tune. Trilby is from drunken Irish-Scottish parents, but is a simple boyish soul who enjoys the company of English gentlemen.

Part Second The unscrupulous and dirty Svengali hypnotises Trilby to cure the pain in her eyes. Little Billee is teased by fellow students at Studio Carrel, but is a good artist. Trilby acts as a housekeeper and friend to three English friends. Svengali makes strenuous amorous advances to her.

Part Third Trilby poses in the nude at Carrel’s studio, which shocks Little Billee. She is upset and decides to give up modelling. Preparations are made for a Christmas feast. Little Billee feels self-righteous after tending a drunken fellow lodger.

Part Fourth A rowdy Christmas dinner takes place at the studio. Little Billee gets drunk and asks Trilby to marry him. In the new year Billee’s mother Mrs Bagot arrives to contest the engagement. Trilby agrees not to marry Billee and leaves Paris with her brother, who dies shortly afterwards. Billee falls ill with the disappointment. He goes back to live in England, and later finds fame as a painter, but he does not recover the power of feeling.

Part Fifth Taffy and the Laird leave Paris and wander around Europe. Five years later they meet Billee who has become successful, but has tired of being taken up by the rich and famous. Billee takes them to a house party where they overhear rapturous accounts of Trilby’s singing voice. Billee goes to Devon where he is smitten by his sister’s friend Alice. He confides his feelings to her pet dog, as well as explaining his anti-religious beliefs.

Part Sixth Taffy, the Laird, and Billee are back in Paris. They visit their old studio. They attend Trilby’s Paris debut, where she astonishes everyone with the artistry of her singing. Billee’s capacity for feeling is restored, but he is consumed by jealousy. Taffy reveals to him that he too once proposed to Trilby.

Part Seventh Next day the three friends see Trilby with Svengali passing in a carriage, but she ignores them all. Svengali assaults Billee, but when a duel is proposed he doesn’t respond. In London Svengali beats Trilby, quarrels with Gecko, and is stabbed by him. Trilby fails to sing at her London debut; Svengali has a heart attack; and Gecko is arrested. Trilby is ill; she denies ever singing; and she recounts her story of the ‘lost’ five years when Svengali rescued her.

Part Eighth Svengali dies, and Trilby goes into physical decline. Mrs Bagot forgives and befriends Trilby, who prepares for her death. On receiving a photograph of Svengali, Trilby goes into a trance and recovers her singing voice for the last time, then dies. Many years later, following Billee’s death, Taffy is in Paris on his honeymoon with Billee’s sister. He meets Gecko, who reveals how Svengali hypnotised Trilby into a creature acting under his own will.

Trilby – principal characters

| Talbot Wynne (Taffy) | an ex-soldier and Yorkshireman |

| Alexander McAlister (Sandy, the Laird) | a Scot and student of painting |

| William Bagot (Little Billee) | a young English art student |

| Mrs Bagot | Billee’s mother |

| Svengali | a Jewish pianist and hypnotist |

| Gecko | a violin player (Polish?) |

| Trilby O’Ferrall | a tall artist’s model |

| Jeannot | Trilby’s little brother |

| Durian | a sculptor |

© Roy Johnson 2016

More 19C Authors

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories