tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

Revenge was written in the early spring of 1924 and was published in

Russkoye Ekho in April 1924. In his list of stories collected for publication in single volume form, Nabokov listed the story under the heading ‘Bottom of the Barrel’, and it was first included in Vladimir Nabokov Collected Stories published by Alfred A. Knopf in New York in 1995.

Vladimir Nabokov

Revenge – critical commentary

This is an early (and rather crude) example of Nabokov’s love of the grotesque, coupled with his penchant for narrative suspense and playfulness, as well as the use of irony and the dramatic twist.

The contents of the professor’s second suitcase are not revealed – but we know that fellow passengers on board the cross Channel ferry think it is something unusual. The professor has previously joked to a student trying to assist him that it is ‘Something everybody needs. Why, you travel with the same kind of thing yourself. Eh? Or perhaps you are a polyp?’

So – we know the professor wishes to murder his wife, but we do not know that the suitcase contains a skeleton. And the suspense generated by these two features of the narrative (and the connection between them) is not resolved until the final words of the story.

The principal irony is that the professor’s young wife actually loves him, even though he is an unattractive bully, and her note to ‘Jack’ is just a girlish piece of romantic nonsense written to an imaginary man who has appeared to her in a dream. But the professor wants her to die in the most excruciating way possible – something he actually fails to achieve, for we are led to believe that she has died of fright.

Nabokov also shows his early love of first person narrators and self-referentiality in fiction – that is, stories that comment upon themselves. In the opening of the narrative a student and his sister are discussing the professor’s appearance and his similarity to a comic actor:

‘He’s really enjoying the sea,’ the girl added sotto voce. Whereupon, I regret to say, she drops out of my story.

Narrators commenting on their own narratives became almost a hallmark of Nabokov’s later works as both a novelist and writer of short stories. It is also worth noting that his narrators sometimes became increasingly unreliable – reaching perhaps what is a highpoint in his novel Pale Fire where Charles Kinbote comments on and interprets another writer’s work – to create a narrative which is an elaborate, gigantic, and very amusing lie.

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon UK

Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon US

Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon US

Revenge – study resources

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov – Amazon UK

![]() Zembla – the official Vladimir Nabokov web site

Zembla – the official Vladimir Nabokov web site

![]() The Paris Review – 1967 interview with jokes and put-downs

The Paris Review – 1967 interview with jokes and put-downs

![]() First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection of photographs

First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection of photographs

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Revenge – plot summary

Part 1 A middle-aged biology professor is travelling back from a scientific congress in Berlin to his home in England. On the Ostend ferry he has two suitcases – one old and well-travelled, the other new and orange-coloured. He has hired a private detective to spy on his much younger wife and received evidence of a love note she has written to a man called Jack. He has therefore determined to murder his wife. At the customs inspection the contents of the orange suitcase amaze his fellow travellers.

Part 2 His young wife who believes in ghosts has written a note to Jack, a man who has appeared to her in a dream, but in fact she loves her husband the professor even though he is jealous of her and very temperamental.

When he arrives home he makes fun of her beliefs then tells her a macabre story about a woman whose body unravels until she is just a corpse. He then goes to bed and tells her to follow him. She prepares herself then joins him in the dark, snuggling up to him under the covers. But her husband has put into their bed the skeleton of a hunchback, and she dies of shock on making contact with it.

Revenge – further reading

![]() Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton University Press, 1990.

![]() Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991.

![]() Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

Laurie Clancy, The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984.

![]() Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

Neil Cornwell, Vladimir Nabokov: Writers and their Work, Northcote House, 2008.

![]() Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

Jane Grayson, Vladimir Nabokov: An Illustrated Life, Overlook Press, 2005.

![]() Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

Norman Page, Vladimir Nabokov: Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1997

![]() David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

David Rampton, Vladimir Nabokov: A Critical Study of the Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

![]() Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Michael Wood, The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Other work by Vladimir Nabokov

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

Pnin is one of his most popular short novels. It deals with the culture clash and catalogue of misunderstandings which occur when a Russian professor of literature arrives on an American university campus. Like many of Nabokov’s novels, the subject matter mirrors his life – but without ever descending into cheap autobiography. This is a witty and tender account of one form of naivete trying to come to terms with another. This particular novel has always been very popular with the general reading public – probably because it does not contain any of the dark and often gruesome humour that pervades much of Nabokov’s other work.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

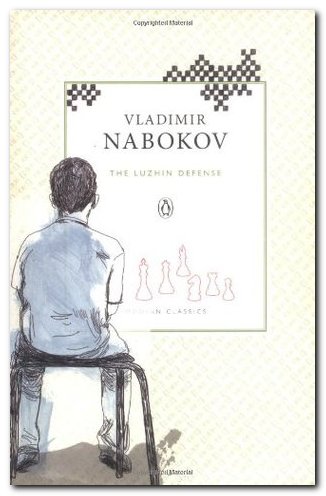

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

Collected Stories Nabokov is also a master of the short story form, and like many writers he tried some of his literary experiments there first, before giving them wider reign in his novels. This collection of sixty-five complete stories is drawn from his entire working life. They range from the early meditations on love, loss, and memory, through to the later technical experiments, with unreliable story-tellers and the games of literary hide-and-seek. All of them are characterised by a stunning command of language, rich imagery, and a powerful lyrical inventiveness.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2014

Pale Fire

Pale Fire

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.