tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

The Double is sometimes known under its German name, the Doppelganger. It is a cultural phenomenon most often present in literature and studies of psychology. The term is used to describe situations in which one person appears to be a duplicate of or a close parallel to another. The scenario is often presented in a manner which cannot easily be explained.

The similarities between the two figures might be physical, or psychological, or both. In some cases the first person is very conscious of being shadowed or threatened by the existence of the second person or double figure. In other cases the two figures are merely presented simultaneously, and the observer (the reader) is left to draw the inference that they are being offered as twin examples of the same or very similar characteristics.

Alternatively, the two figures might throw psychological light on each other. They are often used in such a way that reflects the complex divisions or contradictions that might exist within an individual personality. These divisions are often known under the collective phrase ‘the divided self’.

In fiction, the unsettling nature of this phenomenon is normally perceived or related from the first person’s (character’s) point of view. That is, the principal character becomes aware of the second character who often threatens, displaces, or triumphs over the first.

The double is sometimes interpreted as an exploration of two sides of the same personality. That is, the fictional creation is perceived as the representation of some innate duality in human psychology. This might be seen as the ‘good’ and the ‘evil’ that are potential in human nature. In such cases the two figures may be presented as opposites – but with some inexplicable attraction to each other or purpose in common.

In Freudian psycho-analytic terms such binary figures can be seen as battles between the Super-ego and the Id, taking place within the individual’s Ego. The human being (Ego) is trying to abide by a set of rules or moral standards dictated by a notion of what is ‘right’. These rules are dictated by the Super-ego or conscience. But the Ego’s efforts are thwarted by the human desire to satisfy all sorts of forbidden or irrational impulses. These deeply submerged impulses are dictated by the Id or the unconscious.

Literary tradition

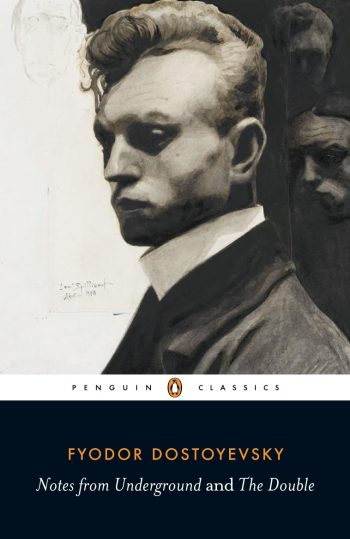

There is a long tradition of stories which deal with ‘the double’ theme. These are narratives featuring a character who feels the presence of, thinks he perceives, or sometimes even sees another character who has the same appearance or name as himself. The second character might succeed in society where the first character fails, or the second might perform some anti-social act for which the first character is blamed. Examples include Edgar Alan Poe’s Wiliam Wilson (1839), Fyodor Dostoyevski’s The Double (1846), and Vladimir Nabokov’s The Eye (1930).

Very often these stories are first person narratives in which it becomes clear to the reader that the second character does not actually exist, but is a projection of the narrator’s imagination – an ‘alternative’ personality, or ‘another self’ representing a fear or a wish-fulfilment.

Very often other characters in the narrative are either unaware of the second ‘doubling’ figure – or they might mistake one person for the other, because they are so similar. You can see some of these variations in the examples that follow.

The Double – further reading

![]() Karl Miller, Doubles in Literary History – Amazon UK

Karl Miller, Doubles in Literary History – Amazon UK

![]() Karl Miller, Doubles in Literary History – Amazon US

Karl Miller, Doubles in Literary History – Amazon US

![]() Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny – Amazon UK

Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny – Amazon UK

![]() Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny – Amazon US

Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny – Amazon US

![]() Otto Rank, Double: A Psychoanalytic Study – Amazon UK

Otto Rank, Double: A Psychoanalytic Study – Amazon UK

![]() Otto Rank, Double: A Psychoanalytic Study – Amazon US

Otto Rank, Double: A Psychoanalytic Study – Amazon US

![]() Andrew Hock, The Double in Literature< – Amazon UK

Andrew Hock, The Double in Literature< – Amazon UK

![]() Andrew Hock, The Double in Literature – Amazon US

Andrew Hock, The Double in Literature – Amazon US

The Double – examples

Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) is a wonderful example of the double presented as two apparent opposites. Victor Frankenstein is young, refined, well educated, and in love with his beautiful fiance Elizabeth. He creates a Monster who is giant-sized, crude, and savagely violent. However, they are locked in a very symbiotic relationship.

Frankenstein and his Monster are like contradictory parts of the same person. The Monster is the active, physical side of Frankenstein (the scholar) but also more obviously the ‘evil’ side. He performs acts almost on Frankenstein’s behalf (to carry out his subconscious wishes) daring to do what Frankenstein can not. As Masao Miyoshi has observed ‘The common error of calling the Monster ‘Frankenstein’ has considerable justification. He is the scientist’s divided self.’

It is possible to take this analysis even further by regarding Frankenstein and the Monster as one and the same being. They are like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The justification for this view turns largely on the fact that Frankenstein is always ‘absent’ when the murders are commuted, and nobody else in the novel ever sees Frankenstein and the Monster together in the same scene. For an essay that explains this interpretation in further detail, see Frankenstein: the romance, the double, the psyche

William Wilson

Edgar Allen Poe’s story William Wilson (1839) (from his famous collection Tales of Mystery and Imagination) is an account of someone who, from his schooldays onward, feels he is being hampered and challenged by a figure who has the same name as himself. Not only has he the same name, but the same birthday, the same clothes, and the ability to appear at crucial moments, issuing warnings and advice.

The double has a habit of appearing at crucial moments, just as William Wilson is going to commit some anti-social act. He ruins a young nobleman by cheating at cards, and finally is about to seduce a young married woman when he is challenged by his conscience and double. He plunges his rapier into the double, only to discover himself in front of a full length mirror covered in blood. In killing his ‘better self’ he has brought about his own death.

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous novella Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) is a perfect example of this literary trope. The story is that Dr Jekyll is an upright and well-respected member of the community in Edinburgh. But a series of malicious attacks on innocent people are perpetrated by a Mr Hyde.

Jekyll and Hyde are polar opposites. Jekyll is tall, upright, honest, and philanthropic. Hyde is small and malignant to the extent that he commits murder. They seem to be representations of the conscious and the unconscious mind – the Ego and the Id. It transpires they are actually one and the same person. Jekyll has been experimenting with drugs that will allow him to transform himself into another identity.

Almost every element in the story has a parallel or a double. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde are two aspects of the same man. Jekyll’s house has two entrances – one the respectable public front entrance, the other a partly hidden, secret, and locked rear entrance. Thus the main subject of the novella is reinforced its thematically linked details.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray features an interesting twist on the ‘double’ theme. There are two two figures in the story – but one of them is a painting. Dorian Gray is a beautiful young man who has his portrait painted at the start of the narrative. He puts the painting in an attic and gives himself up to a life of self-indulgence.

As the years go by his ego centrism is responsible for the suffering of people around him, and he even kills a close friend – and yet he remains as youthful and beautiful as ever. However, the painting in the attic is meanwhile ageing.

Eventually he is oppressed by feelings of guilt, but feels that the painting has somehow cheated him. He resolves to destroy it, but in the final scene the painting has become young again, whilst Dorian is dead with a knife in his heart – a wrinkled, withered, and age-ravaged old man.

The painting acts as an ‘objective correlative’ of Dorian Gray’s self-indulgence, and the evil his corruption has generated, whilst leaving him apparently unchanged in outward appearance. The image of ‘a painting in the attic’ has become a popular metaphor and reference when commenting about people who seem to have unfairly escaped the ageing process.

The Secret Sharer

Joseph Conrad’s celebrated novella The Secret Sharer (1910) is explicitly packed with the features of the double theme. Its young unnamed narrator is a ship’s captain who at night takes on board an escapee from another nearby ship. This man Leggatt, has saved his own ship during a storm but in doing so has killed a malicious fellow seaman.

The young captain and Leggatt are of similar age. They attended the same elite sailor’s training school. They are both bare footed when they meet. The captain gives Leggatt his own sleeping suit to wear, so that they look the same, and he puts him into his own bed in order to conceal him. The captain immediately (and throughout the tale) refers to Leggatt as his ‘double’ and ‘secret self’. Leggatt was chief mate on the Sephora – and presumably the young captain had previously been a mate before promotion to captain.

The two men echo each other’s gestures. The captain feels that they are both ‘strangers on board’. Leggatt is a stranger because he comes from another ship, the captain is a stranger in that he has only recently taken up his command. The captain refers to Leggatt as if he is looking in a mirror. Eventually, he assists Leggatt to evade detection and allows him to escape to a nearby island.

Conrad often creates stories in which someone is presented with a moral dilemma or an existential crisis. This experience might also involve confronting ethically complex situations or other characters who have dared to cross the line between good and evil.

The Eye

As a Russian novelist, Vladimir Nabokov was very well aware of the double tradition in literature, and used the device frequently – often to comic or macabre effect. In his early novella The Eye (1930) he creates a neurotic un-named first person narrator who is a double in two senses. First he attempts suicide half way through the story, and then afterwards (having failed) refers to himself in the third person, as if he were observing himself from outside the story. He claims ‘In respect to myself I was now an onlooker’.

Then in the second part of the story he circulates in fashionable society where he meets a man called Smurov. He finds this man very charming and attractive, attributing to him all sorts of positive virtues and social success. Smurov however behaves in a clumsy and insensitive manner, and is eventually revealed as a liar. It becomes clear to the reader that Smurov and the narrator are one and the same person.

In this variation on the double theme it is the narrator who is a failure, and he makes his double a success – a projection of what he wishes to be. But because he is a hopelessly neurotic person, his efforts fail.

Despair

In his novel Despair (1932) Nabokov offers a further variation of the double theme. His first person narrator Hermann decides to fake his own death in order to claim on an insurance policy. At the same time he also wishes to commit the ‘perfect crime’. In order to do this he finds a man whom he believes to be his exact double. He befriends this man (Felix), they exchange clothes, and he then murders him.

The story is related entirely from Hermann’s point of view, but Nabokov scatters clues throughout the tale which enable the reader to realise the truth. Felix is nothing like Hermann: he is not a double at all. Hermann is deranged, and at the end of the story he in hiding, waiting to be arrested by the police.

The renaissance double

We can see from these examples that the double was largely a phenomenon of the nineteenth century. But since it now seems to reveal something fundamental about human consciousness, it is also possible to see examples in earlier works. For instance, it is possible in a renaissance work such as Othello to see the two main characters of Othello and Iago as opposite sides of the same character

Othello is proud, honest, unsophisticated, and some would say naive. Iago on the other hand is scheming, deceitful, and villainous. They also both have designs on the same woman – Desdemona. Iago is the murky, unprincipled sub-conscious or id to Othello’s super-ego. Iago will stoop to any depths to achieve his ends, whilst Othello is doing only what is right until he is tricked into murdering his own wife – still thinking he is doing right

A Tale of Two Cities

There are elements of the double in A Tale of Two Cities. The hero of the novel is Charles Darney, an upright and honourable young Englishman. His opposite is Sydney Carton, a disreputable and alcoholic lawyer who takes a cynical and self-serving view of everything that life presents to him. Yet the two men look like each other, and they are both in love with the same woman – Lucy Minette

When Darney is eventually captured by the French revolutionaries and imprisoned in the Bastille, Carton secures his escape and offers himself as a look-alike substitute. He goes to his death on the guillotine as an act of noble self-sacrifice saying ‘It is a far better thing I do than I have ever done’. The once dissolute Carton redeems himself personally and morally by the sacrifice of his wicked self to his good self.

© Roy Johnson 2017