from hobby to major cultural enterprise

The Hogarth Press 1917-1987 was established by Leonard Woolf in 1917 as a therapeutic hobby for his wife Virginia Woolf who was recovering from one of her frequent bouts of ill-health. It was named after Hogarth House in Richmond, London, where they were living at the time. Its first manifestation was a small hand press which they installed on the dining table in their home. They also bought two boxes of type, which was used to hand-set the texts they produced. Working from a sixteen page instructional handbook, they taught themselves how to set the type, lock it up in chases, and print a decent page. Their first project, Two Stories, was a thirty-one page hand-printed booklet containing a story by each of them – Leonard’s Two Jews and Virginia’s The Mark on the Wall. One hundred and fifty copies were printed and bound on their dining table and sold by subscription amongst friends. These are now highly valued collectors’ items. (See the book jacket and a bibilographic description.)

More small books followed, many of them written by their friends. Fortunately for the success of the Press, they just happened to be connected with the most amazingly avant-guard (and yet popular) names of their day. The list of people published by the Hogarth Press is like a role call of cultural modernism: Katherine Mansfield, E.M. Forster, and T.S. Eliot. They even went on to become the official publishers of the works of Sigmund Freud, via their connections with James Strachey – his English translator and brother of their friend Lytton Strachey.

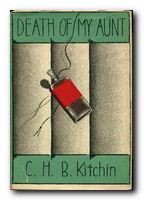

Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter Vanessa Bell. Other covers in the early series were designed by Dora Carrington and Roger Fry. The jacket covers were considered very modern for the period, and they helped to establish a recognisable house style, which contributed to the success of the Press.

Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter Vanessa Bell. Other covers in the early series were designed by Dora Carrington and Roger Fry. The jacket covers were considered very modern for the period, and they helped to establish a recognisable house style, which contributed to the success of the Press.

Within ten years, the Hogarth Press was a full-scale publishing house and included on its list such seminal works as Eliot’s The Waste Land, Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room and Freud’s Collected Papers. Leonard Woolf remained the main director of the publishing house from its beginning in 1917 until his death in 1969.

There was no formal agreement about policy: they simply published work which they liked or thought was important. They did all the most menial tasks of running a small home-based publishing business themselves. Virginia spent hours wrapping up books in brown paper parcels and tying them up with string for dispatch to booksellers. She even set the text of The Waste Land by hand, using a compositor’s stick.

In 1921 the Press was equipped with more sophisticated printing equipment and moved to new premises in Tavistock Square. It also began to publish translations of works of Russian literature by writers such as Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Checkhov, and Gorky.

Virginia Woolf is now well known for her love-affair with fellow writer Vita Sackville-West. What is not so well-known is that Sackville-West’s work, such as her long poem The Land (1926) and her novel All Passion Spent (1931) was also published by the Hogarth Press. In fact it sold far more copies than Woolf’s work at the same time. She was a best-selling writer in every sense of the term, making money for the Press and handsome royalties for herself. It’s to her credit that even when wooed by other publishers promising her larger advances, she stayed loyal to the firm. The Land was awarded the prestigious Hawthornden Prize for literature in 1926, which added to the firm’s prestige.

Virginia Woolf is now well known for her love-affair with fellow writer Vita Sackville-West. What is not so well-known is that Sackville-West’s work, such as her long poem The Land (1926) and her novel All Passion Spent (1931) was also published by the Hogarth Press. In fact it sold far more copies than Woolf’s work at the same time. She was a best-selling writer in every sense of the term, making money for the Press and handsome royalties for herself. It’s to her credit that even when wooed by other publishers promising her larger advances, she stayed loyal to the firm. The Land was awarded the prestigious Hawthornden Prize for literature in 1926, which added to the firm’s prestige.

Leonard Woolf kept the accounts for all commercial activity with the same rigour and the attention to detail that he had learned from his days as a colonial administrator. He made it a policy to answer every letter he received the same day as it landed on his desk. Each penny that went in or out of Hogarth Press was noted by him with anal-retentive exactitude – though as one of his many assistants records, this also reveals something of his dual nature:

Leonard himself was, in general, cool and philosophical about the ups and downs of publishing: his fault was in allowing trifles to upset him unduly. A penny, a halfpenny that couldn’t be accounted for in the petty cash at the end of the day would send him into a frenzy that often approached hysteria… On the other hand, if a major setback occurred – a new impression, say, of a book that was selling fast lost at sea on its way from the printers in Edinburgh – he would display a sage-like calm, and shrug his shoulders.

As their enterprise became more successful and the volume of business grew, they felt they needed more help. A succession of younger men were employed to help run the Press – many of them aspirant young writers themselves. Amongst them was Richard Kennedy, a sixteen year old boy, who recorded his very amusing memories of the experience in A Boy at the Hogarth Press. Others included Ralph Partridge, George Rylands, Angus Davidson and John Lehmann.

As their enterprise became more successful and the volume of business grew, they felt they needed more help. A succession of younger men were employed to help run the Press – many of them aspirant young writers themselves. Amongst them was Richard Kennedy, a sixteen year old boy, who recorded his very amusing memories of the experience in A Boy at the Hogarth Press. Others included Ralph Partridge, George Rylands, Angus Davidson and John Lehmann.

John Lehmann was the longest lasting and the most serious member of the firm, He was the brother of actress Beatrix Lehmann and novelist Rosamund Lehmann, and he had two spells of employment. He worked first as an apprentice manager from 1931 to 1932. Then in 1938 when Virginia Woolf chose to give up the practical drudgery of packing and typesetting, he bought out her share and returned as part-owner and general manager.

He had ideas to transform the Hogarth Press from a cottage industry into a fully-fledged modern publishing business, and he proposed that they should raise share capital and employ publicists and agents. But his ambitions were antithetical to all Leonard’s principles of self-reliance, independence, and control. Leonard argued – quite rightly as it turned out – that the strength of the Press was its independence and its policy of working with minimum overheads and outlay. He stuck to his guns, and was proved right in the end. Lehmann describes the conflict of views from his point of view in Thrown to the Woolfs, whilst Leonard gives his version of events (complete with balance sheets) in his magnificent Autobiography.

In 1939 the Press moved to Mecklenburgh Square, but it was bombed out in September 1940 during the first air raids on London. A temporary refuge was found with its printers, the Garden City Press, in Letchworth.

Curiously enough, as John Lehmann records in his account of these years, these disasters proved to be a benefit to the press. Its editorial offices and stock rooms were in the same building as its printers, and both were a long way away from London, where other publishers were suffering losses to their inventory as a result of air raids during the war. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, sales rose, because of general shortages: “Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.”

Curiously enough, as John Lehmann records in his account of these years, these disasters proved to be a benefit to the press. Its editorial offices and stock rooms were in the same building as its printers, and both were a long way away from London, where other publishers were suffering losses to their inventory as a result of air raids during the war. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, sales rose, because of general shortages: “Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.”

Priority was given to keeping Virginia Woolf’s works in print even after her death, as well as the works of Sigmund Freud which the Press had started to publish. Other writers whose work appeared around this time were Henry Green, Roy Fuller, and William Sansom.

However, following Viginia’s death in 1941, there remained only two essential decision makers on policy. Without her casting vote, the differences between Lehmann and Leonard Woolf grew wider and led to clashes. Lehmann wanted to publish Saul Bellow and Jean Paul Sartre, but Leonard said ‘No’. There were also misunderstandings about income tax returns and the foreign rights to Virginia’s work.

Disagreements rumbled on until after the war had ended. When the final split between them came about in 1946, Leonard solved the financial problem of raising £3,000 to keep the company afloat by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. The Hogarth Press became a limited company within Chatto & Windus, on the strict understanding that Leonard Woolf had a controlling decision on what the Hogarth Press published.

Disagreements rumbled on until after the war had ended. When the final split between them came about in 1946, Leonard solved the financial problem of raising £3,000 to keep the company afloat by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. The Hogarth Press became a limited company within Chatto & Windus, on the strict understanding that Leonard Woolf had a controlling decision on what the Hogarth Press published.

Ian Parsons was the husband of Trekkie Parsons, who had illustrated some Hogarth titles. She lived with Leonard during the week and with her husband at weekends – so they became business partners as well as sharing a wife. The slightly bizarre nature of this relationship is recorded in their collected Love Letters.

In the period after 1946, the most important books published by the Press were the multi-volume editions of Virginia Woolf’s Diaries and Letters, the twenty-four volume set of The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (1953-1974), as well as Leonard Woolf’s Autobiography. Following Leonard’s death in 1969, ownership of the Press was transferred to Random House UK in 1987 when it bought out Chatto & Windus.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

I would like to use 3 lines of a poem by C.P. Cavafy published by the Hogarth Press in 1984 translated by Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard.

The first 3 lines of the poem Ionic would be used as an intro to a psychological thriller called The Goddess Awoke set in Crete.

I would be grateful for permission or advice.

Requests for permission to quote from a work should always be addressed to the publisher.

I can’t imagine there will be any problem with only three lines.

Good luck – with the request and the thriller!