tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Story of a Masterpiece first appeared in The Galaxy magazine in January 1868. It was not reprinted during James’s own lifetime, and its next appearance in book form was as part of the collection Eight Uncollected Tales of Henry James published in New Brunswick by Rutgers University Press in 1950.

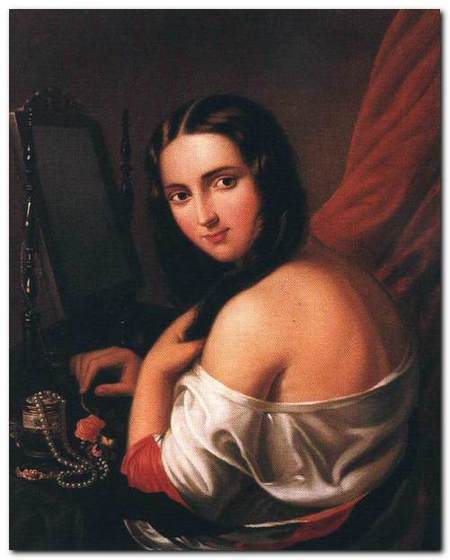

A Potrait of a Woman

The Story of a Masterpiece – critical commentary

The Painting

There are two interesting points of note here. The first is the direct reference to Robert Browning’s well known poem, My Last Duchess which features an Italian Duke showing somebody a portrait of his former wife who he has murdered. Baxter refers to his earlier portrait of Marian, somewhat ironically, as ‘My Last Duchess’ – because he was engaged to her at the time it was first started. The irony is lost on Lennox, who does not know the full truth of his wife-to-be’s past at that point in the story. Though Baxter does not have Marian murdered, but he does break off their engagement because he discovers she has a dubious reputation.

The second item of interest is James’s attempts to present different interpretations of paintings in a literary text. We as readers of course have no image to see, but he offers a persuasive account of how the earlier and the later portraits of Marian might reflect the painter’s attitude towards his model – or are perceived by their principal viewer Lennox according to his attitude to the sitter. When Lennox is enamoured of Marion he thinks the portraits wonderful, but as soon as he suspects her of deception, he views them as revealing her duplicity. This is a little precursor of modernist critical theory at work on the subjective nature of perception. And of course the magical literary trick is that there is no original portrait against which any interpretation can be judged. We only have the painting as described in the text.

And of course the fate of the painting – hacked to pieces because of the corruption it reveals to its owner – is a powerful precursor to the famous scene ot the end of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) when Dorian destroys both his own idealised image as a young man, and himself as the older and corrupt reality.

The ending

The story originally ended as described in the synopsis below. The painting is destroyed, and we are left in doubt about the outcome of the wedding – though on the whole it seems likely that it will still take place, even though the destruction of the portrait suggests that Lennox has seen a glaring weakness in Marian’s character. But James was prevailed upon by the editor of The Galaxy magazine to add the following paragraph to make the ending more explicit for his readers:

I need hardly add that on the following day Lennox was married. He had locked the library door on coming out the evening before, and he had the key in his waistcoat pocket as he stood at the altar. As he left town, therefore, immediately after the ceremony, it was not until his return, a fortnight later, that the fate of the picture became known. It is not necessary to relate how he explained his exploit to Marian and how he disclosed it to Baxter. He at least put on a brave face. There is a rumour current of his having paid the painter an enormous sum of money. The amount is probably exaggerated., but there can be no doubt that the sum was very large. How he has fared – how he is destined to fare – in matrimony, it is rather too early to determine. He has been married scarcely three months.

James was only young at the time, and would understandably feel compelled to comply with the wishes of an editor. But it is interesting to note that he re-introduces the element of doubt into the conclusion by saying ‘it is rather too early to determine’ the outcome of the marriage.

The story certainly fits well with others written around the same time which feature the duplicity and fickleness of women. This is certainly not an isolated instance. In his very first story A Tragedy of Error (1864) an unfaithful wife hires someone to kill her husband; in The Story of a Year (1865) a young woman vows to be faithful to her fiancé whilst he is away at war, and breaks her promise within a very short time; and in A Landscape Painter (1866) a young woman accepts a man’s proposal of marriage, then later reveals that she does not love him and has only married him for his money.

The Story of a Masterpiece – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Story of a Masterpiece – plot summary

Part I

Rich widower John Lennox becomes engaged to poor but pretty Marian Everett in Newport during the summer holidays When they return to New York he visits his friend Gilbert and finds Stephen Baxter painting a portrait he calls ‘My Last Duchess’ which looks surprisingly like Marian. Lennox offers to buy it, but someone else has already bought it.When he tells Marian the news, she reveals that she met Baxter in Europe. Lennox then arranges for Baxter to paint Marian’s portrait.

It is then revealed that Marian became engaged to Baxter whilst in Europe, but both being poor, they agreed to wait until there was an improvement in Baxter’s fortunes. But Baxter overhears a story of Marian’s having been indiscreet with another young man. He checks the story with Mrs Denbigh and discovers that there have been two indiscretions with men who were both rich and handsome. Baxter breaks off his engagement to her.

A year and a half passes before they meet up again in New York, at which point Baxter has gotten over his anger and disappointment. He now finds Marian shallow, and reveals to her that he has become engaged to a girl he left behind in Germany.

Part II

The commissioned portrait is eventually finished. It is a faithful likeness of Marian, but when Lennox contemplates it he feels that it reveals her essential heartlessness. Baxter feels some sympathy with Lennox, but when they inspect the portrait together Lennox is suspicious of Marian and Baxter’s past connection. Baxter admits that he was once in love with her – and Lennox convinces himself that it is Baxter’s disappointment at being rejected by Marian (as he believes) that shows through in the portrait.

Baxter does not betray Marian by revealing the truth of the matter. Lennox then questions Marian about her past with Baxter, but she is evasive. Nevertheless, she is worried that he might be disenchanted with her.

As the day of the marriage draws closer, Lennox feels more ill at ease. He sees the portrait on public display, alongside ‘My Last Duchess’ which he now thinks inferior. He contemplates buying his way out of the engagement by giving Marian all his money and escaping. The portrait is delivered to his home on the eve of the wedding, whereupon he hacks it to pieces.

The Story of a Masterpiece – characters

| John Lennox | a rich (millionaire) thirty-five year old widower |

| Marian Everett | a pretty but penniless young woman |

| Gilbert | a painter friend of Lennox |

| Stephen Baxter | a painter friend of Gilbert |

| Mrs Denbigh | Marian’s chaperone in Europe, a distant relative of Baxter |

| Sarah | Baxter’s fiancée |

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories