tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Years (1937) was the largest of Virginia Woolf’s novels. Its focus is the passage of time as it traces the Pargiter family history from 1880 up to the ‘Present Day’. The novel met with high praise when it was first published. David Garnett said the book “marks her as the greatest master of English” and is “the finest novel she has ever written” (New Statesman & Nation). Subsequent critical assessments have been more mixed. The novel sold very well in England and America making its way on to American best-seller lists.

Elizabeth Willson Gordon, Woolf’s-head Publishing: The Highlights and New Lights of the Hogarth Press

The Years – critical commentary

In 1922 Virginia Woolf broke with the conventions of traditional prose fiction in her experimental novel Jacob’s Room. This involved abandoning plot and suspense; adopting a shifting point of view; and creating a discontinuous narrative which switched from one character and location to another, with few marks of transition or causality in between.

The same techniques are at work in The Years, but the sense of fragmentation and the lack of unity is exacerbated by the fact that Woolf cut whole swathes out of her original composition – leaving enormous gaps between the ‘chapters’ or ‘sections’ of the novel in which events are left unrecorded and unexplained.

We know from Woolf’s original manuscript of the novel (when it was called The Pargiters: A Novel-Essay) that this is the most heavily edited and revised of all her novels. As Mitchell Leaska points out in his introduction to the published manuscript version:

many parts of the novel are highly ambiguous. Throughout the published text of The Years we come across splinters of memory, fragments of speech, titles of quoted passages left un-named or forgotten, lines of poetry or remnants of nursery rhymes left dangling in mid-air, understanding between characters incomplete, and utterances missing the mark and misunderstood. In one sense the novel eloquently communicates the failure of communication.

The reader is able to reassemble some sense of what has happened in those gaps by piecing together hints that are dropped in the remaining sections – but it has to be said that one of the weaknesses of The Years is that the narrative offers very little incentive for this effort to be made.

There is quite a bewildering array of characters, and keeping track of them is not made any easier by the fact that many of them are known by their pet names or nicknames. Magdalena is known as Maggie, Sally as Sara, and Nicholas Pomjalovsky is called Brown. It is interesting to note that the only character who appears all the way through the novel and provides some sense of continuity is Eleanor, who is not given a nickname.

There are also characters who appear in the narrative, assume a certain importance in the events of the section (or chapter) in which they appear – only to disappear and never be mentioned again. This might well reflect the facts of social life as we experience it, but it does not make for a very compelling work of literary art.

There are other problems too. We know that uppermost in Woolf’s mind during the composition of the novel were issues of women’s roles in society – materials for which she wisely cut out of the novel and eventually found their way into Three Guineas. But having cut them out, the novel is curiously denuded of political content.

The section entitled 1914 ends with a rhapsodic scene of Kitty wallowing in her sense of ownership on her family estate ‘in the North’ – with absolutely no mention of the catastrophe about to engulf Europe – which we know to have been an active concern for society at the time.

It might be argued that the character’s lack of awareness is a criticism of upper-class complacency in the face of international power-politics – but unfortunately the same thing is true of the final section of the novel Present Day in which the whole family assembles for a party in 1937 without any mention of the second catastrophe into which Europe was sliding. This is at best curious and at worst a serious flaw – especially when we know that Woolf herself lived in a milieu in which international politics was an active and regular subject of debate.

Authors are not obliged to use their own lives for the material of their fictions of course, and it could be argued that Woof is showing a typical upper-class family in all its privilege and neglect – but there is very little sense of criticism within the text.

The Years – study resources

![]() The Years – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Years – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Years – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

The Years – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Years – Wordsworth Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Years – Wordsworth Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Years – Wordsworth Classics edition – Amazon US

The Years – Wordsworth Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Years – Vintage Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Years – Vintage Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Years – Vintage Classics edition – Amazon US

The Years – Vintage Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() Virginia Woolf – biographical notes

Virginia Woolf – biographical notes

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Selected Essays – by Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

Selected Essays – by Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

The Years – plot summary

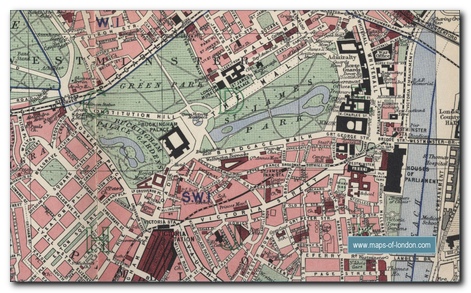

1880. Colonel Pargiter leaves his club in Piccadilly and visits his mistress in Westminster. Then he goes home and joins his children for afternoon tea. His daughter Delia goes upstairs to visit her mother who is an invalid, whilst another daughter Rose defies house rules and goes out to the shops. Later, whilst the family are having dinner, Mrs Pargiter has a fainting fit, and there is a general feeling that she is dying. That evening Rose is frightened by the image of a man she has seen exposing himself in the street.

At Oxford University Edward Pargiter is cramming for an examination in Greek. He share a gift of port with two fellow undergraduates Hugh Gibbs and Ashley. Kitty Malone (a relative of the Pargiters) goes to a history lesson with Lucy Craddock, then has tea with the poorer Robsons, which she enjoys compared with the stiffness of college life. News arrives of Mrs Pargiter’s death, and both branches of the family take part in the funeral service, which is viewed sceptically by Delia.

1891. Eleven years later Milly Pargiter has married Hugh Gibbs. Eleanor is running the family home for her ageing father and supervising repair works on the lodgings of the poor. She has lunch with her father then goes to the law courts to watch her brother Morris try a case, but she leaves feeling oppressed by the atmosphere in court. In the busy London streets, learning that Parnell has died, she visits her sister Delia in a poor rooming house – but she is not at home.

Colonel Partiger is in town on the same day, having ended his relationship with Maria. He visits the home of his brother Digby and sister-in-law Eugenie, feeling envious of Digby’s domestic comforts.

1907. Sir Digby and Lady Eugenia Pargiter are on their way to a summer evening party with their daughter Magdalena (Maggie). Whilst they are out their very imaginative younger daughter Sara (Sally) lies in bed listening to the sounds of a dance in a house nearby, turning over philosophic concepts of being and reading Edward Pargiter’s translation of Antigone.

Her sister and mother return late at night and the young girls pester their mother for romantic anecdotes about her younger life.

1908. A year later Sir Digby and Lady Eugenia Pargiter have both died. Martin Pargiter, back from India and Africa, visits their house, which has been closed and sold. He then visits Eleanor and his father, who has had a stroke. Rose visits from her suffragette work in the North. The siblings resurrect memories of childhood.

1910. Rose, now forty, visits her cousins Maggie and Sara who live in poor ‘rooms’ in a working class area south of the river. They compare memories of childhood and their respective families. After lunch, Rose takes Sara to a political meeting in Holborn where Eleanor is the secretary. It is also attended by Kitty (Lady Lasswade) who afterwards is driven to the opera (Siegfried) where she is joined by her cousin Edward, who is still a bachelor.

Maggie and Sara finish their dinner, after which Sara gives a slightly dotty but accurate account of the meeting. Their neighbourhood is full of noise and drunks, and the section ends with the announcement that Edward VII has died.

1911. Old Colonel Pargiter has died. Eleanor, now fifty-five, returns from a trip to Mediterranean countries to visit Morris at his mother-in-law’s house in Dorset, where she meets an old friend Sir William Whatney. She wonders what to do with her life now that she has no more domestic responsibilities.

1913. Eleanor sells the family house, and Crosby the housekeeper retires to Richmond. However, she still looks after Martin’s laundry. He lives in Ebury Street, Belgravia and is still not married.

1914. Martin leaves home and walks towards the city where he is due to see his stockbrokers, wondering what he might have been had he not been in the army. At St Paul’s he meets Sally and takes her for lunch to a very crowded chop house. She gets tipsy, then rather cryptic and mystical in her conversation. Afterwards they take a bus, then walk through Hyde Park into Kensington Gardens where she is due to meet Maggie. Martin confides in Maggie about a woman with whom he is unhappily in love.

In the evening he goes to a formal dinner party given by Kitty in Grosvenor Square. He is bored by the extremely stiff and lifeless conventions of upper-class society, but he does what is expected of him. He and Kitty both claim to be interested in each other, but do nothing about it.

After the guests leave Kitty changes and is driven to the station where she catches the night train for the family estate in the ‘North’. She arrives in the very early morning, and after breakfast goes for a walk on the estate, feeling an ecstatic bond with the countryside and a sense of continuity and ownership, even though she knows that the estate will pass into the hands of her eldest son.

1917. Eleanor goes to dinner with Maggie and Renny in Westminster where she meets the gay Pole, Nicholas. They are joined by Sara who rapidly becomes tipsy. When an air raid starts, they move down into the cellar and continue dinner there. Various responses to the war are expressed in fragments of unfinished conversation. After the raid is over the visitors leave and rejoin the almost empty streets where traffic is beginning to circulate again

1918. An ageing and ailing Crosby is shopping in Richmond, clinging on to the last domestic position that separates her from poverty.

Present Day. Eleanor, now in her seventies, has been to India. Her nephew North returns from sheep farming in Africa to visit Sara, having been impressed by Nicholas . They discuss their previous correspondence and have a low class dinner where she boards. Eleanor and Peggy (who is now a doctor) travel to Delia’s house to a party, their fragments of conversation reflecting links to the past and differences in generations within the family.

North and Sara exchange their enthusiasm for poetry and anti-Semitism whilst waiting to go to the party. They are joined by Renny and Maggie. At the party Peggy has to politely endure boring stories from her uncle, whilst she is quietly reflecting on what we can know about other people. The younger Pargiters (now in their sixties and seventies) meet and tease each other about incidents in their shared childhood.

North feels an outsider’s rage against the stiff social conventions and views the party as degenerate animals which ought to be destroyed. Eleanor meanwhile tries to make sense of the long life she has lived, but in the end she falls asleep.

Eleanor eventually feels that she finds happiness simply being amongst younger living people. Peggy on the other hand is painfully conscious of the hardships and misery in life. She criticises North in an unprovoked attack. North feels himself completely alienated, and sees the guests as a middle and upper-class club to which he does not belong.

North meets his uncle Edward and admires him for what seems to be his attitude of being above the mediocre mass, and he wishes to find some new way of being for himself. Nicholas tries to make a speech of thanks to the hostess, but he cannot command attention. Finally, as dawn breaks over the square, the party comes to an end and the guests begin to go home.

The Years – principal characters

| Colonel Abel Pargiter | head of the family, with two fingers missing |

| Rose Pargiter | his invalid wife, who dies |

| Eleanor Pargiter | the eldest daughter (‘no beauty’) who does charity work |

| Milly Pargiter | daughter |

| Rose | daughter, imaginative suffragette and spinster |

| Martin | son, who joins the army |

| Morris | son, apprentice at law, who becomes a barrister |

| Edward | Oxford university classics scholar |

| Dr Malone | an Oxford Don |

| Rose Malone | his wife, Rose Pargiter’s cousin |

| Kitty | his large daughter, later Lady Lasswade |

| Lucy Craddock | Kitty’s private history tutor |

| Celia | Morris’s wife, Eleanor’s sister-in-law |

| Sir Digby Pargiter | Colonel Pargiter’s younger brother |

| Eugenie | his wife |

| Magdalena (Maggie) | his daughter |

| Sally (Sara) | his daughter |

| René (Renny) | a Frenchman |

| Nicholas Pomjalovsky (Brown) | a gay Pole |

| North | Morris’s son, Eleanor’s nephew |

| Crosby | the Pargiter’s housekeeper |

| Mira | Colonel Pargiter’s mistress |

The Years – further reading

Charles Hoffmann, ‘Virginia Woolf’s Manuscript Revisions of The Years‘, PMLA 84 (1969), 78-89.

Mitchell A. Leaska, ‘Virginia Woolf, the Parteger: A Reading of The Years‘, Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 80/2 (1977), 172-210.

Mitchell A. Leaska (ed.) The Partigers by Virginia Woolf: The Novel-Essay Portion of ‘The Years’ (London: Hogarth Press, 1978).

Jane Marcus, ‘The Years as Greek Drama, Domestic Novel and Gotterdamerung’, Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 80/2 (1977), 176-301.

Victoria Middleton, ‘The Years: “A Deliberate Failure”‘ Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 80/2 (1977), 158-71.

Madeline Moore, ‘The Years and Years of Adverse Male Reviewers’, Women’s Studies 4 (1977), 247-63.

Grace Radin, ‘I am not a hero: Virginia Woolf and the First Version of The Years‘, Massachussetts Review, 16 (1975), 195-208.

Grace Radin, Virginia Woolf’s The Years: The Evolution of a Novel (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1981).

Eric Warner, ‘Reconsidering The Years‘, North Dakota Quarterly, 48/2 (1980), 16-30.

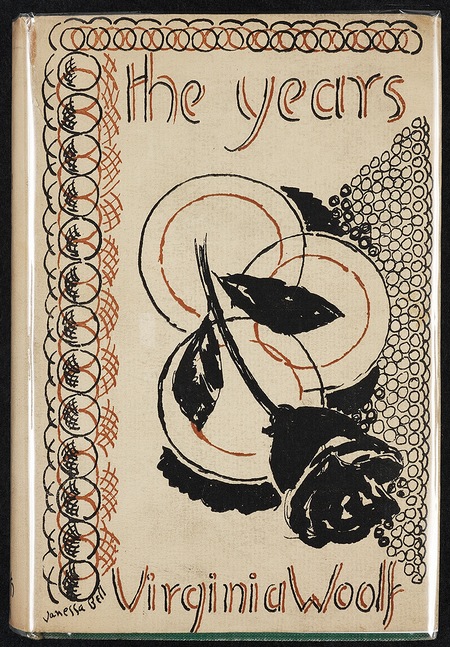

First edition – cover design by Vanessa Bell

The Years – textual history

The novel we now know as The Years has an extremely complicated genesis – both in conception and execution. The first glimmerings of its birth appeared in 1931 when Virginia Woolf delivered a speech to the London branch of the National Society for Women’s Service, an organisation which dealt with employment for women. It was entitled ‘Professions for Women’ and dealt with her own experiences as a writer. She contrasts the comparative ease of her own entry into the world of letters with the heroic efforts of Ethel Smyth the composer:

She is of the race of the pioneers: She is among the ice-breakers, the window-smashers, the indomitable and the irresistible armoured tanks who climbed the rough ground; went first; drew the enemy’s fire; and left a pathway for those who came after her.

During the two years that followed, Woolf was doing the reading and research for what would eventually become both The Years and Three Guineas, but at first these formed one work in her mind. In October 1932 she began work on The Partigers: A Novel-Essay. Her plan was to alternate ‘extracts’ from the novel with essays offering critical commentary on the fictional narratives. The subject of the novel was to be what we now call a ‘family saga’ covering the lives of the Partiger family between 1880 and 2023.

By January 1933 she had completed the first part of the book, which deals with the year 1880 – and it is interesting to note that the essay portions come before the fictional chapters. But a month later, having decided that this formal construction made the work too much like propaganda, she decided to leave out the intervening essays. This material was not lost however: it was to form the basis of what eventually became Three Guineas.

For the next two years she produced 200,000 words of a novel for which she didn’t even have a title. It was at various stages called Here and Now, Music, Dawn, Sons and Daughters, Daughters and Sons, Ordinary People, The Caravan, and Other People’s Houses, before she eventually settled on The Years.

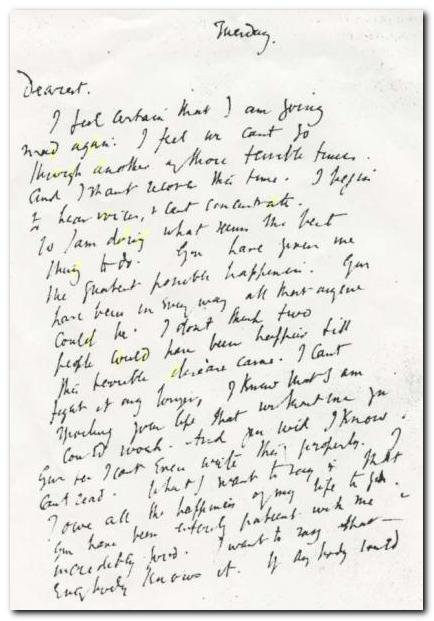

Next came the task of editing down this mass of material into what would be a single publishable volume. She did this by a process of ruthless pruning and simply leaving out explanatory passages, so that the narrative jumps from one character and scene to another with no smooth transitions. Even so, the typescript still came to 740 pages. She did all this editing and re-typing work herself, and the book put a great strain on her fragile mental and physical health. She described it as the novel which almost killed her.

But there was more work to be done. She wanted the work printed in galley proofs before she allowed her final judge, husband Leonard, to read the novel: these proofs amounted to 600 sheets. The strain of all this, the indecision, and the fact that she had been paid in advance by her American publishers, put an enormous strain on her fragile state, and led to a severe illness which lasted three months. Leonard gave his guarded approval to the results, knowing that any censure from him would lead to her complete breakdown.

When she returned to editing the proofs she cut out what she described as ‘two enormous chunks’ (fifty pages of the current OUP text). When the final proofs appeared, one set was edited for the American market and the other for the Woolf’s own Hogarth Press. There are even differences between these two sets of revisions – but relatively minor.

After all this indecision, anguish, and revision, The Years was quite successful on publication, and in America even became a best seller. By the end of 1938 the novel had earned her £4,000, which in contemporary terms is worth between £300,000 and £400,000.

Virginia Woolf’s writing

“I feel certain that I am going mad again.”

Other works by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of the novels The Voyage Out, Night and Day, Jacob’s Room, and the collection of stories Monday or Tuesday in a variety of digital formats.

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

A collection of well and lesser-known photographs documenting Woolf’s life from early childhood, through youth, marriage, and fame – plus some first edition book jackets – to a soundtrack by Philip Glass. They capture her elegant appearance, the big hats, and her obsessive smoking. No captions or dates, but well worth watching.

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group