free pages from our English Language software program

Prepositions – definition

![]() Prepositions express a relationship between nouns (or pronouns) and some other part of the sentence.

Prepositions express a relationship between nouns (or pronouns) and some other part of the sentence.

![]() It usually tells us where something is.

It usually tells us where something is.

Examples

with out in under over around

Use

![]() A preposition is used with a noun or pronoun.

A preposition is used with a noun or pronoun.

The child ran around the snowman.

Jack and Jill went up the hill.

![]() However, the same words are adverbs in the following statements:

However, the same words are adverbs in the following statements:

Let’s take a walk around.

My lucky number came up.

He came over to me.

![]() They are adverbs because they tell us about the verb.

They are adverbs because they tell us about the verb.

![]() NB! Prepositions often tell us about position, so don’t underestimate them.

NB! Prepositions often tell us about position, so don’t underestimate them.

![]() Prepositions are mainly used in English to form adverbial and adjectival phrases, as in the following:

Prepositions are mainly used in English to form adverbial and adjectival phrases, as in the following:

Adverbial phrases

‘Marseilles is in France’

[‘in France’ tells us where Marseilles is]‘Hastings stands on the south coast of England’

[‘on the south coast of England’ tells us where Hastings stands]‘The grocer marvelled at the arrival of the boxes’

[‘at the arrival’ tells us when the grocer marvelled]‘She left the hall with a toss of her head’

[‘with a toss of her head’ tells us the manner in which she left]

![]() All the prepositions above are used adverbially to tell us more about the verb in each case.

All the prepositions above are used adverbially to tell us more about the verb in each case.

![]() The following are examples of adjectival phrases. In each case the preposition describes a noun:

The following are examples of adjectival phrases. In each case the preposition describes a noun:

Adjectival phrases

‘The first cable across the Atlantic was laid in 1838′

[‘across the Atlantic’ describes the cable]‘I love the sound of the sea’

[‘of the sea’ describes the sound]‘I believe that the man in the moon exists’

[‘in the moon’ describes the man]‘We all enjoyed the cheese on toast that our mother gave us’

[‘on toast’ describes the cheese]

![]() Prepositions are usually used, as in the two sets of examples above, with a noun or a pronoun.

Prepositions are usually used, as in the two sets of examples above, with a noun or a pronoun.

![]() Examples of nouns from the sentences given above are ‘the arrival’, ‘a toss’, ‘ the moon’ and ‘toast’.

Examples of nouns from the sentences given above are ‘the arrival’, ‘a toss’, ‘ the moon’ and ‘toast’.

![]() Prepositions can also be used as adverbs without an accompanying noun or pronoun.

Prepositions can also be used as adverbs without an accompanying noun or pronoun.

Come in Turn round Go up Jump off Look around Go under

Self-assessment quiz follows >>>

© Roy Johnson 2003

English Language 3.0 program

Books on language

More on grammar

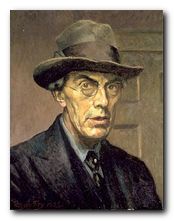

Roger Fry was an influential art historian and a key figure in the

Roger Fry was an influential art historian and a key figure in the

In 1933 Fry was offered the post of Slade Professor at Cambridge and began a series of lectures on the nature of art history that he was never to complete. The text for the lectures was published after his death in 1939 as Last Lectures. Fry died on 9 September 1934 following a fall at his London home. His ashes were placed in the vault of Kings College Chapel, Cambridge, in a casket decorated by Vanessa Bell.

In 1933 Fry was offered the post of Slade Professor at Cambridge and began a series of lectures on the nature of art history that he was never to complete. The text for the lectures was published after his death in 1939 as Last Lectures. Fry died on 9 September 1934 following a fall at his London home. His ashes were placed in the vault of Kings College Chapel, Cambridge, in a casket decorated by Vanessa Bell.

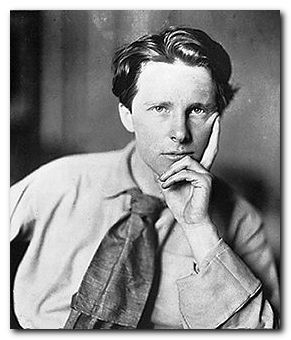

Rupert Brooke (1887—1915) was only ever on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group – but he was well acquainted with its central figures, such as

Rupert Brooke (1887—1915) was only ever on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group – but he was well acquainted with its central figures, such as